Metal particles released by worn-out brake pads may have the same harmful effects on the immune system as diesel exhaust fumes, according to new research.

Lab tests have shown dust from the component can cause inflammation of the lungs and reduce the ability of immune cells to kill bacteria, increasing the risk of respiratory infections.

The effects of air pollution particles from diesel emissions have been well documented, with studies linking the exhaust fumes to lung cancer, various respiratory illnesses and decreased lung function.

A team from King’s College London now believes brake dust could be contributing not only to endless coughs and colds among city dwellers, but also to more serious illnesses like pneumonia or bronchitis.

Dr Ian Mudway, who led the research at the MRC Centre for Environment and Health at King’s College London, said: “At this time the focus on diesel exhaust emissions is completely justified by the scientific literature, but we should not forget, or discount, the importance of other components, such as metals from mechanical abrasion, especially from brakes.

“There is no such thing as a zero-emission vehicle and as regulations to reduce exhaust emissions kick in, the contribution from these sources are likely to become more significant.”

It is estimated that metal particles from brake wear is responsible for up to a fifth of fine air pollution particles, known as PM2.5, at roadsides.

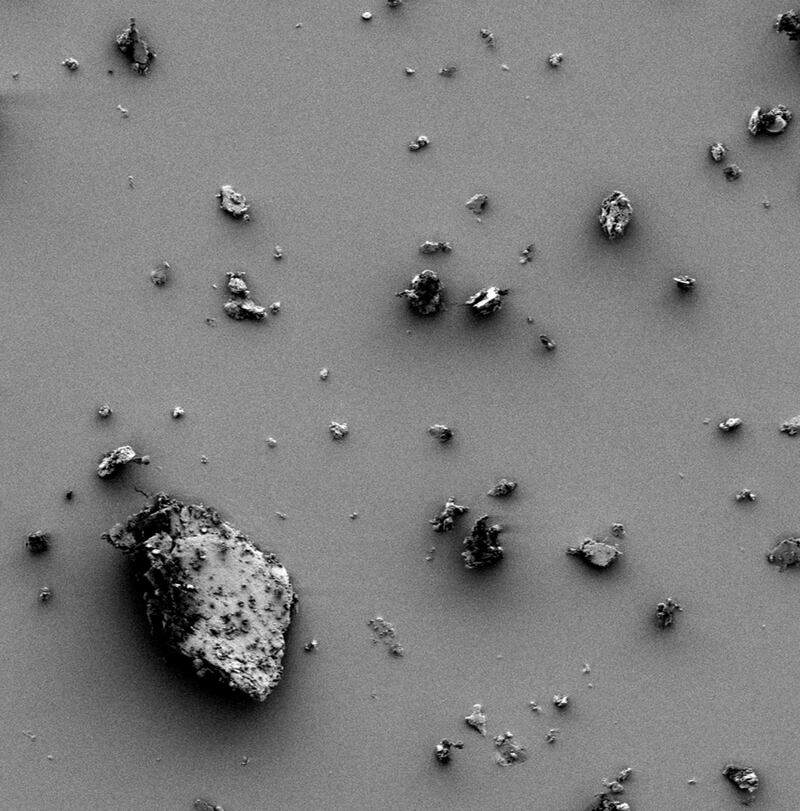

To test the effects of brake pad particles on human lungs, the team collected dust from a brake pad testing factory and exposed it to a group of immune cells, known as macrophages, in the lab.

Macrophages are the lungs’ front-line defence system which kill bacteria by engulfing and digesting them.

When exposed to particulates from diesel exhaust and brake dust, the researchers found the ability of the macrophages to take up and destroy bacteria was reduced.

In addition, the team observed that particulates from both sources caused the macrophages to produce molecules in the immune system which drive inflammation.

Dr Liza Selley, who conducted the research at the MRC Centre for Environment and Health at King’s College London and Imperial College London, said: “Diesel fumes and brake dust appear to be as bad as each other in terms of toxicity in macrophages.

“Macrophages protect the lung from microbes and infections and regulate inflammation, but we found that when they’re exposed to brake dust they can no longer take up bacteria.

“Worryingly, this means that brake dust could be contributing to what I call ‘London throat’ – the constant froggy feeling and string of coughs and colds that city dwellers endure – and more serious infections like pneumonia or bronchitis which we already know to be influenced by diesel exhaust exposure.”

The scientists believe that vanadium, a metal present in both brake dust and diesel exhaust, may be responsible for the harmful effects on immune cells.

The team say further studies are needed to understand more about the effects of brake dust on human health.

The research was funded by the Medical Research Council and is published in the journal Metallomics.