With the rise of artificial intelligence, many are asking questions as to what a future full of robotic assistants will look like, and what does it mean socially, morally and ethically for humans.

Welcome to the setting of Detroit: Become Human.

The latest adventure game from Quantic Dream, the studio behind Heavy Rain and Beyond: Two Souls, is set in Detroit in 2038, where androids are now prevalent as helpers, assistants and arguably slaves to humans.

Taking control of three different androids, players enter a widely branching narrative game, where each decision can directly impact not just that moment, but other characters and the entire universe in which the game is set.

So, how does it play?

Story

The game centres around three androids, Kara, Markus and Connor. Kara and Markus are both assistant or housekeeper types of android, looking after owners at opposite ends of the economic spectrum, while Connor is a special design assigned to work with the city’s police department to investigate cases of androids going deviant.

Kara and Markus quickly see their respective situations change, as Kara flees with the daughter of her owner in order to protect her from a volatile domestic situation, while Markus is cast out after an accident.

Both must then find their way and place in the world, searching for freedom in different ways.

Meanwhile, Connor’s investigation into deviants places a stark choice in front of him – to follow his mission as a Blade Runner-style android hunter, or begin to question its legitimacy.

Gameplay

As is a trademark of Quantic Dream games, Detroit’s gameplay is centred around a decision-making, branching narrative of interactive drama.

Players are constantly presented with a range of options on not only dialogue but also the tone in which they say it, their instinctive physical reaction to a sudden event or a certain route they would like to take towards a goal.

The game’s main narrative moments are also broken up by sessions of seemingly mundane tasks – household chores are a large part of both Kara and Markus’ early appearances. But those moments are far from covert tutorials, it is here that players can explore their surroundings and pick up pieces of information that can unlock new branches in future chapters.

Each character’s own scanning capabilities (launched by holding the R2 button) also form a major part of gameplay. It can be used to help highlight a key point of interaction nearby, and in Connor’s case find evidence when analysing a crime scene.

At these moments, the game mechanics are at their best, as Connor pieces together events and is then able to playback simulations of events, which players can scroll through in search of further clues. It’s a visceral experience and gives the impression you’re piecing together a gritty case.

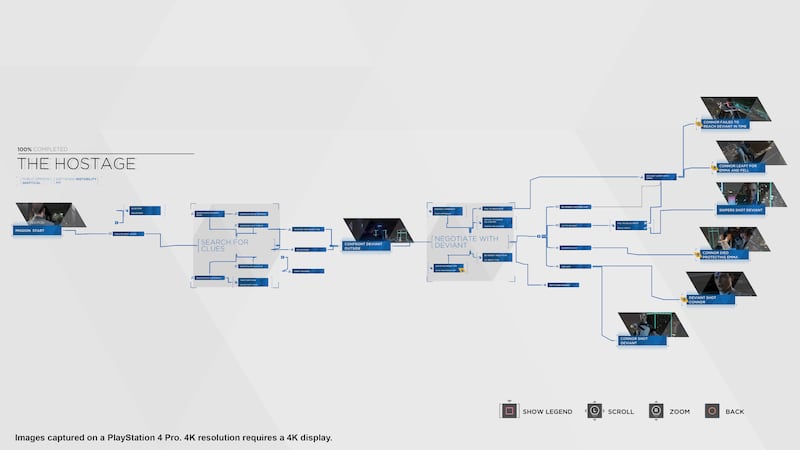

The Flowchart is also a fascinating addition to this type of gameplay. It gives a clear sense of how a user’s choice during a chapter impacted on how the game unfolds, but also tantalisingly shows the other paths a scene can take.

From the main menu, players can go back and replay scenes if they so wish, to see how different actions produce different results and ultimately change the story going forward.

In terms of demonstrating depth and replayability, it’s a striking feature and one that is very engaging to use.

But Detroit’s gameplay isn’t without its flaws, the camera angles, though manually controllable, feel limited at times, and player movement can be bumpy and awkward when the viewing angle automatically changes at some points as players move through a scene.

Experience

There is no doubt that Detroit wants to ask questions and encourage debate not only around the growth of AI and robotics in society but also the issue of race, segregation and persecution among different parts of humanity today.

Striking scenes such as protesters on the streets of the game and segregated buses where androids must stay at the back of the vehicle are meant to trigger links to real life as you play.

The developers would argue that this heightens the power of the game’s interactive drama and decision-making and that is most certainly true – Detroit serves up plenty of gripping scenes and encounters, often drawing in others not playing the game to sit and watch alongside the player in our experience.

However, there are moments where the game feels as though it’s reaching too much for melodrama – some sections feel as though every scene, no matter how calm it begins, has to end in a dramatic stand-off, or are trying too hard to make a political or social reference.

Occasionally the dialogue feels slightly forced together too. For much of Detroit it’s seamless, but on a couple of choice moments, scenes feel a little cut together, as though the pace or attitude being shown wasn’t there a moment ago, with nothing to have triggered it.

Because much of the cinematic nature of the game is exceptional – Detroit is by far the best looking and most vibrant world Quantic Dream has created – perhaps such moments stand out even more.

Verdict

Detroit: Become Human is the perfect game if you’re looking for something that isn’t a run and gun shooter or linear adventure game. It’s gritty and interesting, full of characters you not only want to see evolve but actively enjoy being part of their development.

In terms of message, Detroit aims high – its bold use of language linked to slavery, segregation and persecution are intended to stir debate within players but fall short in terms of delivering a clear opinion of its own, asking lots of questions but offering few answers.

But few narrative experiences will match Detroit in the current generation’s games – the interactive drama is engaging and constantly interesting – enough so to appeal to even the most casual of gamers looking for a new experience.

In interactivity terms, Detroit: Become Human is modern storytelling at its finest, and should be commended for that, even if it falls short of making the powerful social statement it hoped to make.