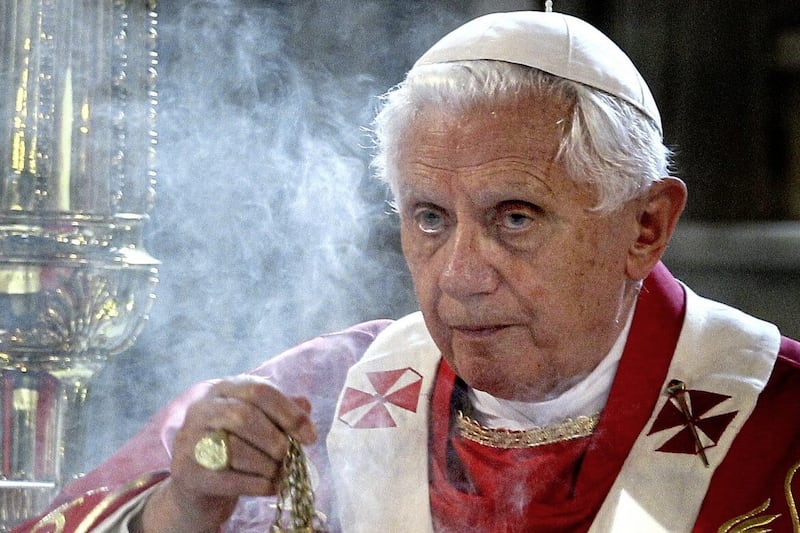

POPE Emeritus Benedict XVI was the first pontiff in 600 years to resign from the job.

The shy German theologian who tried to reawaken Christianity in a secularised Europe stunned the world on February 11 2013, when he announced that he no longer had the strength to run the 1.2 billion-strong Catholic Church that he had steered for eight years.

His dramatic decision paved the way for the conclave that elected Pope Francis as his successor. The two popes then lived side-by-side in the Vatican gardens, an unprecedented arrangement that set the stage for future "popes emeritus" to do the same.

The former Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger never wanted to be pope, and had planned at the age of 78 to spend his final years writing in the "peace and quiet" of his native Bavaria. However, he inherited the seemingly impossible task of following in the footsteps of John Paul II when he was elected on April 19 2005. Benedict became the oldest pope in 275 years and the first German in nearly 1,000 years.

He was forced to follow the footsteps of the beloved St John Paul II and run the church during the fallout from the clerical sex abuse scandal. A second scandal erupted when his own butler stole his personal papers and gave them to a journalist.

Being elected pope, Benedict once said, felt like a "guillotine" had come down on him. Nevertheless, he set about the job with a single-minded vision to rekindle the faith in a world that, he frequently lamented, seemed to think it could do without God.

Benedict relaxed restrictions on celebrating the old Latin Mass and launched a crackdown on American nuns, insisting that the church should stay true to its doctrine and traditions in the face of a changing world.

It was a path that in many ways was reversed by his successor, Francis, whose mercy-over-morals priorities alienated the traditionalists who had been so indulged by Benedict.

Benedict's style could not have been more different from that of John Paul or Francis.

Once nicknamed "God's Rottweiler" by the media, he was no globe-trotting media darling or populist. But the widely-misunderstood Benedict was a teacher, theologian and academic to the core: quiet and pensive but with a fierce mind. He spoke in paragraphs, not soundbites.

It was Benedict's devotion to history and tradition that endeared him to members of the traditionalist wing of the Catholic Church. For them, Benedict remained even in retirement a beacon of nostalgia for the orthodoxy and Latin Mass of their youth - and the pope they much preferred over Francis.

Like his predecessor, Benedict made reaching out to Jews a hallmark of his papacy. His first official act as pope was a letter to Rome's Jewish community and he became the second pope in history, after John Paul, to enter a synagogue.

In his 2011 book, Jesus Of Nazareth, Benedict made a sweeping exoneration of the Jewish people for the death of Christ, explaining biblically and theologically why there was no basis in Scripture for the argument that the Jewish people as a whole were responsible for Jesus's death.

Yet Benedict also offended some Jews who were incensed at his constant defence of and promotion toward sainthood of Pope Pius XII, the Second World War-era pope accused by some of having failed to sufficiently denounce the Holocaust.

They also harshly criticised Benedict when he removed the excommunication of a traditionalist British bishop who had denied the Holocaust.

Benedict riled Muslims with a speech in September 2006 - five years after the September 11 attacks in the United States - in which he quoted a Byzantine emperor who characterised some of the teachings of the Prophet Muhammad as "evil and inhuman", particularly his command to spread the faith "by the sword".

A subsequent comment after the massacre of Christians in Egypt led the Al Azhar center in Cairo, the seat of Sunni Muslim learning, to suspend ties with the Vatican that were only restored under Francis.

The Vatican under Benedict suffered some notorious PR gaffes, with the pope himself being to blame on occasion.

He enraged the United Nations and several European governments in 2009 when, en route to Africa, he told reporters that the Aids problem could not be resolved by distributing condoms.

"On the contrary, it increases the problem," Benedict said. A year later, he issued a revision, saying that if a male prostitute were to use a condom to avoid passing HIV to his partner, he might be taking a first step towards a more responsible sexuality.

But Benedict's legacy was irreversibly coloured by the global eruption in 2010 of the sex abuse scandal, even though, as a cardinal, he was responsible for turning the Vatican around on the issue.

Documents revealed that the Vatican knew about the problem and yet turned a blind eye for decades, at times rebuffing bishops who tried to do the right thing.

Benedict had first-hand knowledge of the scope of the problem, since his old office - the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, which he had headed since 1982 - was responsible for dealing with abuse cases.

In fact, it was he who, before becoming pope, took the then-revolutionary decision in 2001 to assume responsibility for processing those cases after he realised bishops around the world were not punishing abusers, but were just moving them from parish to parish, leaving them free to carry out more attacks.

And once he became pope, Benedict essentially reversed his beloved predecessor, John Paul, by taking action against the 20th century's most notorious paedophile priest, the Rev Marcial Maciel.

Benedict took over Maciel's Legionaries of Christ, a conservative religious order held up as a model of orthodoxy by John Paul, after it was revealed that Maciel sexually abused seminarians and fathered at least three children.

In retirement, Benedict was faulted by an independent report for his handling of four priests while he was bishop of Munich. He denied any personal wrongdoing but apologised for any "grievous faults".

As soon as the abuse scandal calmed down for Benedict, another one erupted.

He made his last public appearances in February 2013 and then boarded a helicopter to the papal summer retreat at Castel Gandolfo, to sit out the conclave in private.

Benedict then largely kept to his word that he would live a life of prayer in retirement, emerging only occasionally from his converted monastery for special events and writing occasional book prefaces and messages.