Huddled around a headstone in London’s Kensal Green on December 2 last, a hardy crowd paid homage to GAA co-founder John McKay.

The wreaths laid by officials from Down, Cork and Britain to mark the centenary of his death demonstrated their pride to have some claim to the legacy of an Irish sporting pioneer.

‘Oh Mary, this London’s a wonderful sight,’ sang John Arnold of Cork, in tribute to a man born beneath the Mournes 171 years before.

The honour of giving a graveside oration fell to me. A constant clank from construction sites carried in the icy wind as I narrated the stories of newspaperman McKay and his wife Nellie, and the tragic tales of their son Patrick Joseph (1887-1929) and infant grandson (born and died in 1917) whose remains lay in the same plot.

The piper played a closing tune. All present agreed that the ceremony had gone well.

I had regrets though. As I had said in my address, the McKay family line didn’t end in that grave. Direct descendants might yet be alive somewhere in England, unaware of their noted Irish ancestors. My efforts to find them in time for the centenary had failed.

Still, I hadn’t lost hope. I left London for home with no new hard evidence, but offers of help and moments of serendipity. For 14 and a half years I had been chasing McKay ghosts; what say I chance a few more months?

The quest began in 2009 when the GAA’s 125 Years Committee sought to ensure that each of the seven founders of the GAA, at Hayes’ Hotel, Thurles, in November 1884, had a suitable memorial.

It soon emerged that McKay was the real mystery. No-one seemed certain where he was even from – Belfast or Cork?

I took up the challenge and recruited aid from a colleague, Kieran McConville. With the help of newly released records, we found that McKay was from County Down and died in London in 1923. A bit more digging revealed that he was buried in Kensal Green in an unmarked grave. And an appeal through this paper uncovered that Downpatrick was his native parish.

Without delay, a gravestone was ordered for McKay, and we travelled to London for its unveiling in 2009.

Justice was done to the distant memory of the only Ulsterman involved in founding the GAA.

Relatives were involved too. Grandniece Philomena McConvey and two great-grandnephews, Danny McKay and Philip Byrne, would attend the unveiling of an Ulster History Circle blue plaque for John McKay at The Irish News offices in Donegall Street in 2010 – McKay had been a journalist at the newspaper in the 1890s, as well as at its forerunner, the Belfast Morning News, a decade before.

Yet I felt there was unfinished business. I had to keep searching for direct descendants.

It wasn’t until late 2018 that I made a breakthrough.

A check for a death notice for Patrick McKay in a newly digitised theatrical newspaper of 1929 revealed that he had a second son, then just a few months old.

Denis Paul McKay went on to have two boys, born in Fulham in 1950-51. So John McKay had not only a grandson (who lived until 2008), but also two great-grandsons who were possibly still living.

Frustratingly, these two boys seemed to vanish from view after their baptisms. Searches of public records yielded no more detail, only that their father remarried a few years later.

Many questions arose. Had their mother died young? Had the boys changed surnames? Were they safe and sound?

I tracked down a will for Denis Paul McKay, who died at Burnham-on-Crouch, Essex, in 2008. It transpired that his estate became bona vacantia – meaning he had no will or known heirs, and the state took whatever he owned. This wasn’t encouraging.

I tried many avenues to find this unnamed heir. I started calling people who might be step-family. “Sorry mate, you’ve got the wrong number,” I was told abruptly more than once

There was a further twist, however. The bona vacantia probate was revoked in 2011. This meant most likely that a legitimate heir had been located. Could this be a son or a distant relative? No more information was available.

I tried many avenues to find this unnamed heir. I started calling people who might be step-family. “Sorry mate, you’ve got the wrong number,” I was told abruptly more than once.

Through the labyrinth I managed to make contact with an ex-partner of the stepson of Denis Paul McKay. That’s far out, of course; but she had attended his funeral, along with only about 10 others.

She knew of no contact between him and his sons, though he had a picture of two little boys in a small photo album. That had to be them.

The approach of John McKay’s centenary in December 2023 provided a target date to find any direct descendants at last. If they were still living, the great-grandsons would be in their seventies now.

The problem is that locating a living person in England can be harder than a dead person.

The main prong of attack was the Treasury Solicitor’s Department in London, in the hope of being told who received Denis Paul McKay’s estate. This entailed four-hour queues on the phone, only to be cut off. Eventually it emerged that this department wouldn’t share such information, even to a solicitor.

As I prepared to travel for the centenary ceremony, it appeared the chief course of action remaining was a concerted appeal to the London Irish. Could anyone remember these two boys growing up in Fulham in the 1950s? London GAA folk certainly offered to try to assist.

I had to use the brief trip to take the lead. I resolved to go to the house where they lived and carry out my own on-street investigations.

I got off the Tube at Fulham Broadway and walked two miles. As I came close, a remarkable sequence appeared in the street signs:

Clonmel Road – that’s Tipperary, where the GAA was formed.

Rostrevor Road – Down, McKay’s native county.

Perpendicular to the street where the boys lived, Munster Avenue – the main fulcrum of McKay’s GAA activity.

And finally, Burnfoot Avenue, where they spent their early years. Burnfoot is a village in Donegal, taking it all back to Ulster.

I knocked on the door of the house that cold evening. A lady answered and patiently heard out my extraordinary request. She declared herself a furniture historian herself and amateur genealogist. She was willing to ask around the street for any lingering memories of the McKays.

I started searching through online archives once more, using various permutations of known names. Then, as I thought back on my serendipitous trail around Fulham and how the street names seemed almost like a yellow brick road, it occurred to me: why not search online records by address?

I typed in Burnfoot Avenue. Incredibly, the eighth and final mention in newspaper archives had it. A letter from a Mrs K Priest, formerly of this address and now living in the Isle of Wight, to the Fulham Chronicle, and referring to her son Patrick McKay having just run the London Marathon of 1982.

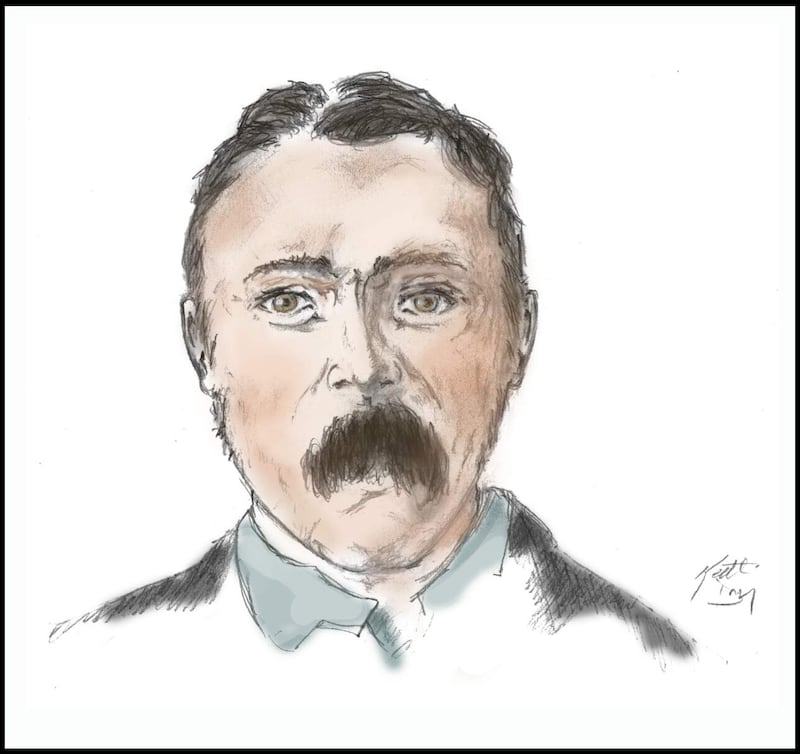

I hotfooted virtually to other channels. I identified a man of this name writing about Isle of Wight matters on social media. I clicked on the link, and, lo and behold, he looked like he could be a direct descendant of John McKay.

One of his friends was a Simon McKay who could be his son and had his own business in Kent, where the family now lives.

Nervously, I prepared to call the business. I feared that I might be rebuffed. Who was I but a mad Irishman? They might not want to know.

‘Hello... Is your father Patrick Terence McKay, born in Fulham in 1950?’

‘Yes.’

Eureka! I managed to sound still a little sane and keep his attention. Within minutes I had emailed the family tree to him.

That night, I had a two-and-a-half hour call with Patrick McKay and his daughter, telling them much of the family history. To my delight, they were willing to embrace it.

It transpired that Patrick knew nothing about his father’s background. He had believed he was from Dundee. He had no clue about a paternal link to Ireland, let alone the GAA.

That said, he said he had always supported London Irish RFC, as he liked their style of play.

There was one more extraordinary vignette. He knew that his maternal line was Irish, for the family had visited Ireland once, in 1957. He had one photograph of that visit – standing in front of the statue of St Patrick in Kilkenny, along with his younger brother Joseph, and both holding camáns.

Not then or in the 66 years till we spoke did he realise his ancestor’s central role in establishing an organisation for hurling and setting its rules.

This week, Patrick McKay has made his maiden trip to Ulster.

On Wednesday he and his daughter, Emilia, visited the ancestral family homestead in Downpatrick and were hosted to dinner by the GAA’s Down County Board.

Yesterday they and Simon attended a function to mark the reinstallation of the John McKay plaque on the new Irish News office at the Fountain Centre in central Belfast, and later another to commemorate Malachians who fought in the First World War (including Patrick’s grandfather, Patrick Joseph McKay).

Also in attendance were several Irish relatives including Fr Brian Watters, based at Belfast’s St Peter’s Cathedral, whose link as a great-great-grandnephew was only discovered the night before. The gathering in turn unearthed the existence of another grand-niece near Oxford, aged 92.

So a family history has come full circle, with a happy ending.

Today, a reception at Croke Park awaits for one of the closest living links to the foundation of the GAA.

It will be a field of dreams come true.