The massacre at Kingsmill in 1976 came amid a week of sectarian bloodshed in Northern Ireland.

The intense spate of tit-for-tat civilian murders began on New Year’s Eve when a pub bomb blamed on a cover group for the INLA killed three Protestants – William Scott, 28, Richard Beattie, 44, and Sylvia McCullough, 31 – in the town of Gilford in Co Down.

Then on January 4, the day before the murder of the 10 Protestant workmen on a dark roadside at Kingsmill, six Catholic men were fatally injured in two separate attacks committed by a notorious Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) gang reputed to contain dozens of rogue security force members.

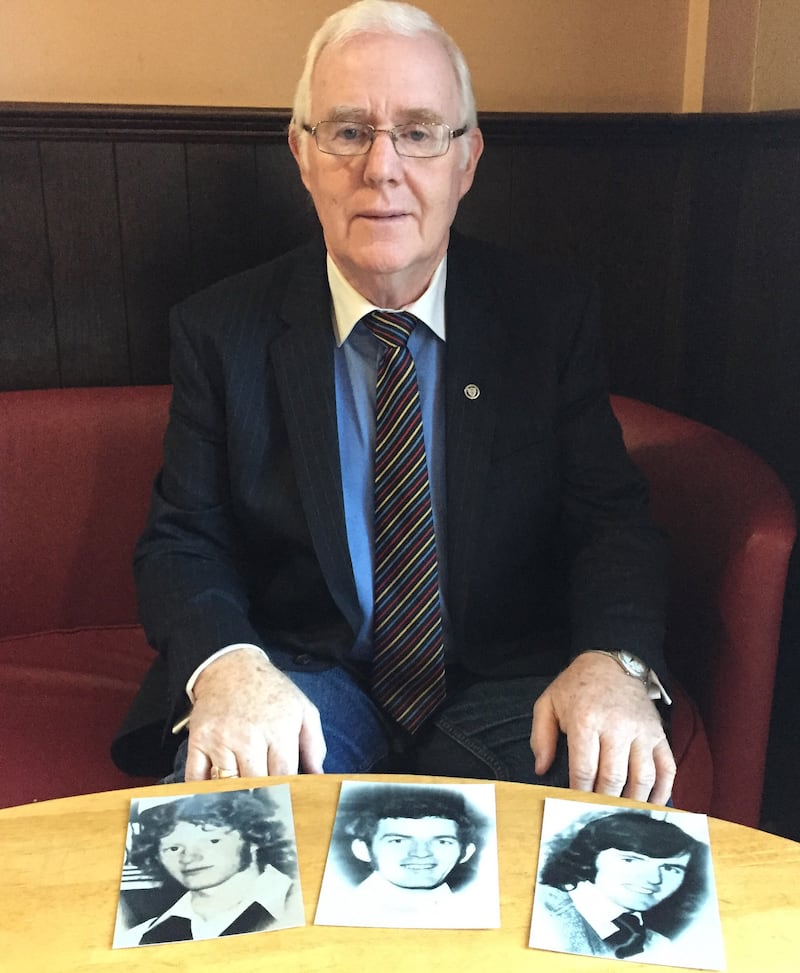

The Reaveys and O’Dowds – two families living within 15 miles of each other – each lost three loved ones at the hands of the Glenanne gang.

Brothers Declan, 19, and Barry O’Dowd, 24, and their uncle Joe, 61, were shot dead at a family gathering in Ballydougan, near Gilford.

Declan and Barry’s father Barney, a member of the SDLP, was seriously injured in the hail of bullets.

The attack took place only minutes after brothers Anthony, 17, Brian, 22, and John Martin Reavey, 24, were shot at their home near the Co Armagh village of Whitecross, close to Kingsmill.

Brian and John Martin were killed instantly while Anthony died weeks later.

The shootings at Kingsmill in the early evening of January 5 by a little-known republican paramilitary group, used as a front for the on-ceasefire IRA, was widely viewed as a retaliatory attack for loyalist targeting of the O’Dowd and Reavey families.

The scale of the loss of life and the naked sectarian motivation of the killers, who ordered the only Catholic on the work minibus to run away, has led Kingsmill to be remembered as one of the most savage atrocities committed during the Troubles.

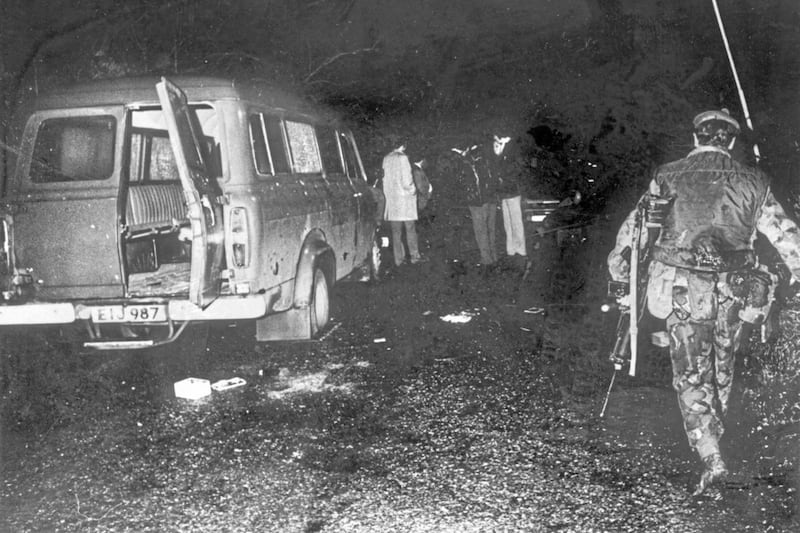

As the red Ford minibus carried the workmen home after a day’s work at the Glenanne textile factory, a car in front slowed significantly, causing the bus to drop into second gear.

The car then drove off but, moments later, a man emerged from a roadside ditch and flagged the bus down with a red light.

He had a clipped English accent and ordered all the occupants to get out of the vehicle and told the driver to turn off the lights.

A group of men with blackened faces, dressed in camouflage gear and black military-style boots and carrying rifles, emerged from the darkness.

Coroner Brian Sherrard described it as a cynical attempt to trick the workmen into thinking they were being stopped by British soldiers as part of an Army checkpoint – something that was commonplace in south Armagh in that period.

The men were ordered to line up and at that point the infamous request for the Catholic to identify himself was made.

Richard Hughes, who was 56 and the only Catholic on the bus, did not speak.

None of his work colleagues identified him either.

The order was interpreted as an attempt to single Mr Hughes out to be killed, rather than to spare him.

However, it was clear the killing gang already knew who Mr Hughes was or had been provided with a description of him.

Eventually the man with the English accent, who was the leader of the murder squad, shouted to “take that grey haired man out”, at which point Mr Hughes was pulled from the line and ordered to run down the road.

He was pursued by two men who pushed him over a fence and into a field.

Throughout, he thought he was being taken away to be shot dead.

Back at the roadside, the same man who had been doing the speaking throughout gave the order to open fire.

A 10-second burst of gunfire followed as the 11 remaining men were sprayed with bullets.

After a brief pause, the gang leader ordered the gunmen to “finish them off”.

A second period of gunfire followed, though this time in the form of single shots fired into the men at close range.

The sole survivor, father-of-three Alan Black, lay among his 10 dying colleagues as they moaned and cried out in pain.

He recalled the youngest victim, 18-year-old Robert Chambers, calling out for his mother.

Mr Black, who was shot 18 times, pretended to be dead.

Although half-conscious, he recalled watching the gunmen calmly walking away from the scene when the shooting finally stopped.

The 10 men who died were Mr Chambers; John Bryans, 46; Reginald Chapman, 29; Walter Chapman, 35; Robert Freeburn, 50; Joseph Lemmon, 46; John McConville, 20; James McWhirter, 58; Robert Walker, 46; and Kenneth Worton, 24.

The IRA, which was supposed to be on ceasefire, never admitted involvement and the murders were claimed by the little-known South Armagh Republican Action Force.

This was widely suspected to be a cover name for the IRA and, in 2011, a police legacy investigations unit – the Historical Enquiries Team (HET) – found that the IRA was responsible and said the workmen were targeted because of their religion.

No-one has ever been convicted for the Kingsmill attack.