Commentators who made unjustified claims that threat, danger and menace was at every turn during the Brexit crisis must now be head-scratching given the DUP’s negotiation with the UK government and subsequent return to Stormont.

Nationalist commentators railed that the DUP would not share power with a Sinn Féin first minister, that Jeffrey Donaldson was playing to the loyalist drum, that he lacked capacity for leadership and feared electoral backlash if he re-entered the Executive. These commentators mimicked the unionist pundits who screamed ‘Not an inch!’ and claimed to be representative of community anger.

The traditionalists of whatever hue are akin to King Lear wandering in the storm, irrationally claiming what they cannot stand over. Neither the unionist nor nationalist version of intransigent thinker understands that storms pass or that politics and how it operates changes over time. They have now gone very quiet on their unfounded claims or refrained from correcting them.

Jeffrey Donaldson may have been aided by nationalist commentators and politicians who claimed the command paper was wrapped in red, white and blue. The same section of nationalism calls repeatedly for the Irish government to plan for unification but then expresses displeasure when the UK government delivers for the DUP – and in so doing showed that London was concerned and remains a strategic interest in Northern Ireland.

Part of that strategic interest is food security, given agribusiness is estimated to feed 10 million UK citizens, and the increasing instability of geopolitics. Northern Ireland as a landing site for fibre-optic technology cables that link North America to the UK is a critical territory for national security.

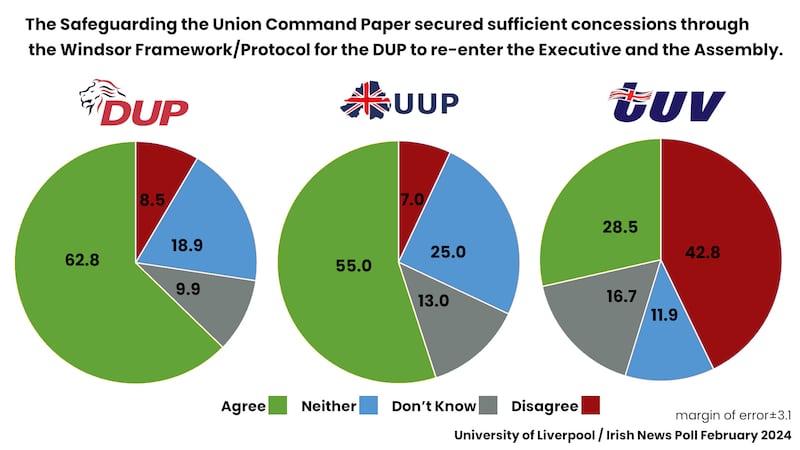

The highest levels of approval for the command paper were evident among DUP voters.

But what crisis will emerge next? Pro-choice, culture and marriage equality legislation have been delivered. The constitutional question will now form centre stage, but the DUP don’t believe there is a constitutional crisis. They are shrewd enough to know that the census and school enrolment data shows the Catholic population is now entering decline, that the southern economy is far from Utopia and that surveys show stability not growth in the numbers for unity.

For example, a recent Arinis survey showed that younger people were slightly less in favour of unity than their older counterparts, while a major ESRC funded project found that among those who were neither nationalist or unionist, 53% compared to 19% favoured remaining in the UK. These surveys were not led or designed by unionists.

The one major problem for the DUP is their lack of synchronisation with the pro-union community who are predominantly socially liberal and feel bruised by the collapsing of the assembly and other behaviours.

The DUP may have sustained the share of vote it got last year but it remains far removed from the vote share achieved in 2019. They have put oil on the water of one crisis, which they created, but now need leadership of a very different type to return as the largest party.

Survey findings suggest they have averted a crisis internally but the question remains how they challenge how Brexit created an electoral crisis for them. That cannot be resolved by negotiation with external agencies but instead via vision from within.