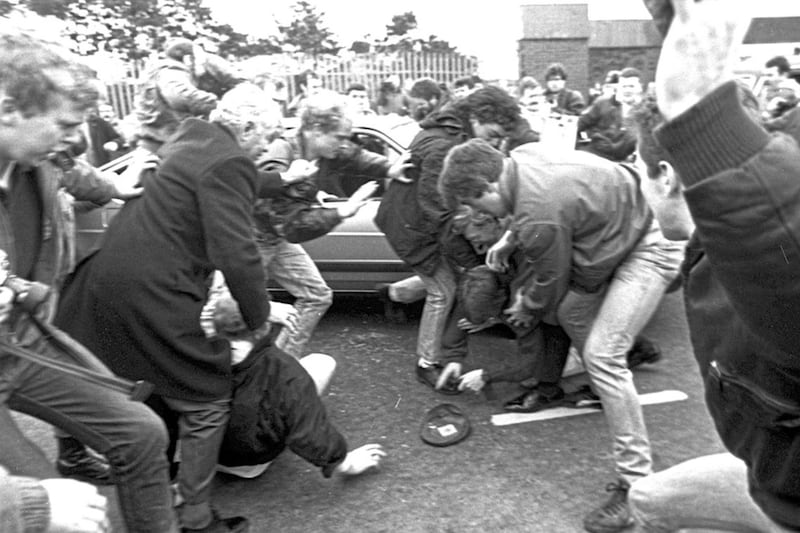

The killing of two British army corporals in Andersonstown 30 years ago, marked a violent end to a traumatic two weeks – bloody days even by the standards of a then raging conflict.

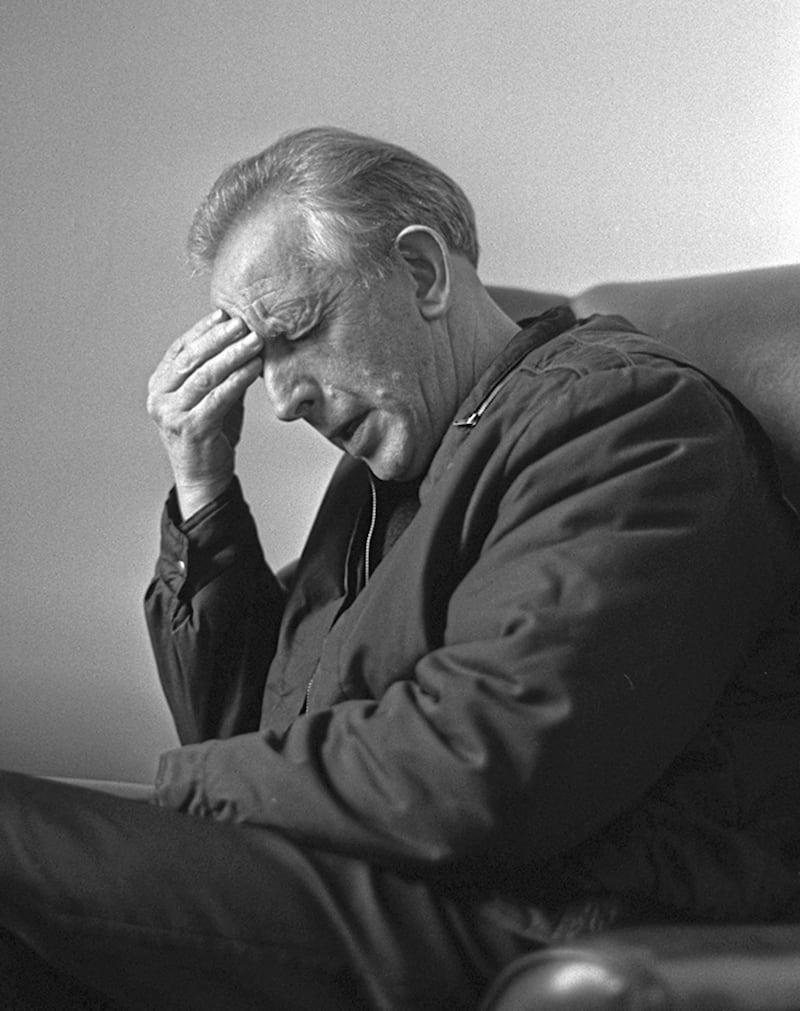

Footage of loyalist Michael Stone attacking mourners in Milltown and the almost biblical picture of the late Fr Alec Reid, crouched over the body of a dead soldier, blood around his mouth where he had tried in vain to resuscitate the murdered man, are gruesome images that most of us are familiar with.

Images that have appeared in countless documentaries, attacks and events that have been written about, debated and dissected by journalists and commentators for 30 years.

To me, my friends, neighbours and family they are not detached news images of horror so unimaginable it appears almost cinema like. To me they are indelible images from my life.

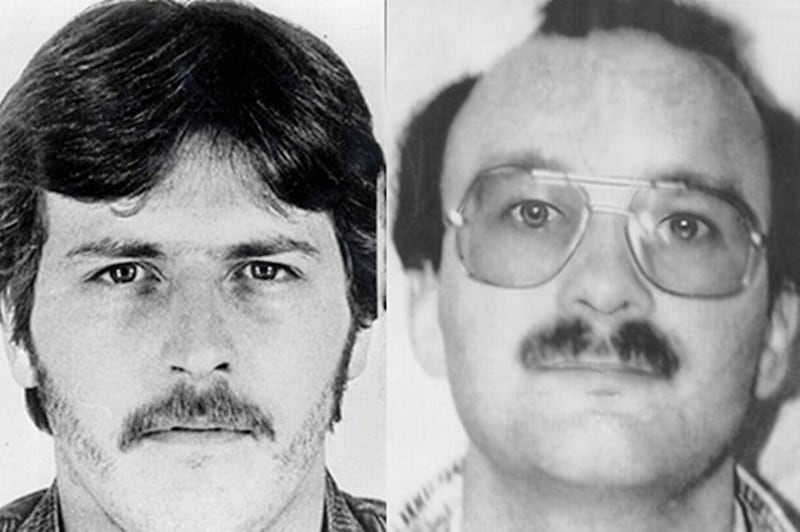

They are part of the reason I chose to become a journalist. The deaths of the corporals David Howes and Derek Wood made for days of global news footage. As a teenager growing up in west Belfast I watched it unfold in front of my eyes.

In 2013, the BBC aired a documentary 14 Days, a sensitively made look at the events of those two weeks back in March 1988.

It was told in the words of Redemptorist priest Fr Reid, who spoke about his efforts to find a way out of the deadly cycle of violence.

The deaths of three IRA members at the hands of the SAS in Gibraltar marked the start of that fortnight.

The funerals of Mairead Farrell, Sean Savage and Dan McCann were attacked by Stone, and it was the funeral of one of those who died in that attack on Milltown cemetery at which the corporals were killed.

At the time there was talk of civil war and a descent into violence so extreme we might never recover from it.

Watching that documentary there was footage of the corporals driving into the funeral cortège and I caught a split second glimpse of someone I thought I recognised, bleached blond hair, terrible eighties denim. It was my much younger self.

I slowed the footage down and showed my children. It’s so grainy it’s hardly worth noting but given what was unfolding around me they were clearly shocked.

"Did you get counselling after that?" my daughter asked innocently.

I was standing at the bottom of Slemish Park at the time, watching the funeral of Caoimhín MacBrádaigh go past.

Funerals in the 1980s were common place, endless grieving processions, sometimes shots would be fired over a coffin, sometimes the RUC would move in and there would be a riot.

These events, 30 years on are now considered part of a dark history, but at the time seemed strangely normal.

I watched the corporal’s car speed into the crowd and them being dragged from it. I can remember the smell of burning rubber in the air from the tyres on their vehicle.

People were screaming, some running away from the car, some

running towards it. Everyone thought it was another loyalist attack, given what had occurred a few days previously.

The crowd thickened and all around me people were speculating as to who the two men were. Many speculated loudly as to why there were no RUC or soldiers moving in to rescue them. A police helicopter was overhead as it always was in those days.

I didn’t see the two soldiers after that but I did hear the thump of their bodies being bundled over a wall at Casement Park.

Years later I was covering a Twelfth of July riot at Woodvale when the police water cannon connected with a man dancing on the bonnet of a Land Rover, his body hit the road surface with a thump making the exact same sound.

As a child the only journalists I ever encountered had posh English accents and the news stories I read in the stack of papers my father brought into our house every morning painted my community as savages, detached from all human decency.

The words did not match with my experience of living in a poor but proud place.

By the end of that fortnight 11

people had died and many more were injured. The negative image of west Belfast was cast by those terrible events. Much of the international reporting provided little or no context.

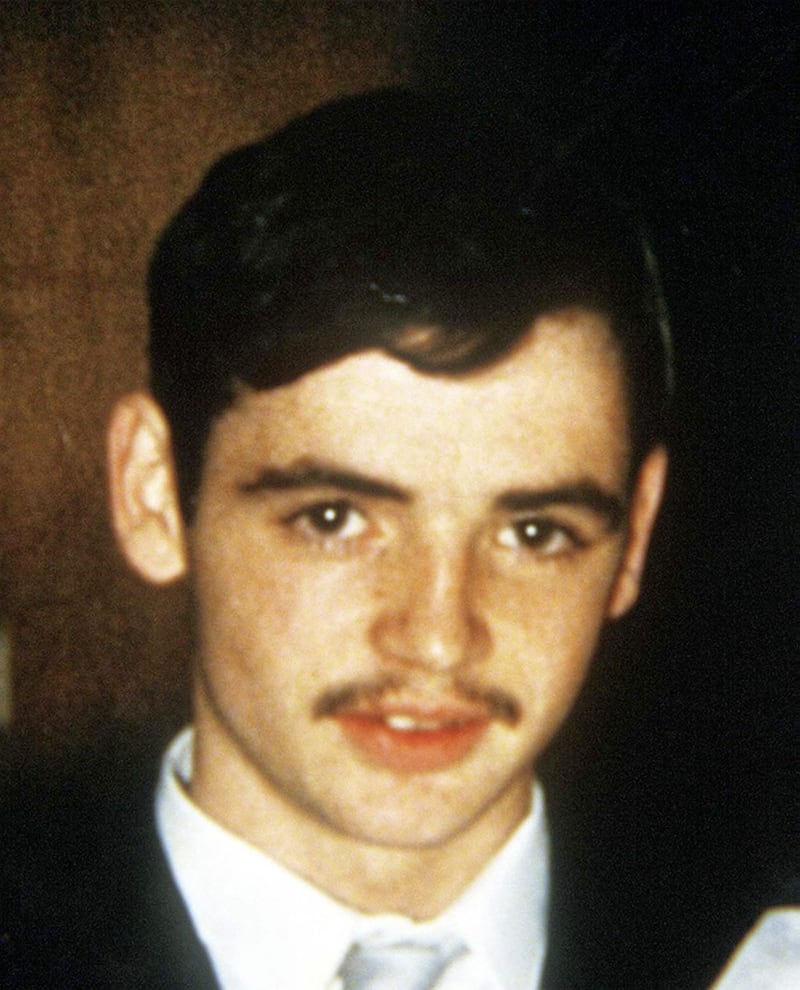

The list of the dead: Mairead Farrell, Sean Savage, Dan McCann, Kevin McCracken, Thomas McErlean, John Murray, Caoimhín MacBrádaigh, Jillian Johnston, Derek Wood and David Howe, some of the names well known others less so their deaths barely receiving coverage at all such was the intensity of the unfolding situation.

Fr Reid revealed later he had been given a letter at the funeral from Sinn Féin to pass to John Hume, when he returned to Clonard it had the blood of David Howes on the envelope. It was a letter that helped kick start the Hume/Adams talks which would eventually lead to the peace process, however, on that day in west Belfast in March 1988 peace was a distant aspiration and Northern Ireland was a very dark place.

****

March 6, 1988 - the SAS shot dead three IRA members in disputed circumstances as they prepared to bomb a British army band in Gibraltar

March 14, 1988 - IRA member Kevin McCracken was shot dead by a British soldier in Turf Lodge, west Belfast as he prepared to attack a patrol

March 15, 1988 - Charles McGrillen was shot dead by the UFF in a sectarian killing in the yard of Dunnes Stores at Annadale Embankment

March 16, 1988 - Thomas McErlean, John Murray and IRA member Caoimhín MacBrádaigh were killed in a gun and grenade attack by loyalist Michael Stone on the funerals at Milltown Cemetery of the IRA members killed in Gibraltar

March 18, 1988 - Jillian Johnston was shot by the IRA in Belleek in Co Fermanagh. The IRA later said the killing was a mistake.

March 19 - British soldiers Derek Wood and David Howes were killed when the corporals drove into the funeral cortège of Caoimhim MacBradaigh