CLASSIC police detective tradecraft involves building a rapport with potential witnesses in the hope of getting them ‘on-side’.

Around seven years ago I agreed to meet an English detective investigating the activities of Stakeknife Freddie Scappaticci and sure enough – and not entirely to my surprise – he had a surprisingly good knowledge of the GAA.

We even discussed the latest Ulster Championship results.

Despite this ‘shared’ interest, I declined an offer to become a witness for the prosecution.

I didn’t feel it was my job as a journalist to assist him – and I also made it clear that day that I felt Operation Kenova would never see Freddie Scappaticci in the dock on murder charges.

There is no way the British would ever allow it, I said. It would be a waste of time, I insisted.

What we will end up with now will be yet another heavily-redacted report on the entire affair confirming what everyone already knew.

We can expect another Stevens Inquiry-style report that will dominate the news cycle for 24 hours and might even make the Channel Four news.

Scappaticci’s death is an aside to the plans of the Tory Government at Westminster in introducing legislation giving an amnesty to everyone for any offence committed prior to Good Friday 1998, but the real purpose of the law is to keep people like Scappaticci – and more importantly his British Army handlers – completely out of the courts.

With his death, that’s at least one problem solved as far as the British are concerned.

Cue the narrative which will now emerge. He will soon be branded a ‘rogue agent’ and there will be claims the British didn’t really have proper control over him; and that they did not know about some of his activities.

When I doorstepped Scappaticci at his home in west Belfast almost 20 years ago, he knew the game was up on his double life in the IRA as a British agent.

When he appeared at a bizarre press conference a few days later to deny my allegations, Scappaticci also knew it was time to get out of town.

A subsequent ‘deny-all’ interview in the Andersonstown News looks even more unusual now.

Protected by a Ministry of Defence injunction he moved to Manchester, where the bill for his new life was picked up by the British Exchequer.

This included trips to see his beloved Manchester City (where he was once a trialist) and trips to the Canary Islands for family reunions. He never got to fulfil his dream of building a retirement home in the Italian town of Cassino, his father’s birthplace.

The families of his victims have faced countless delays for justice and will now have to settle for a redacted UK police report via Operation Kenova.

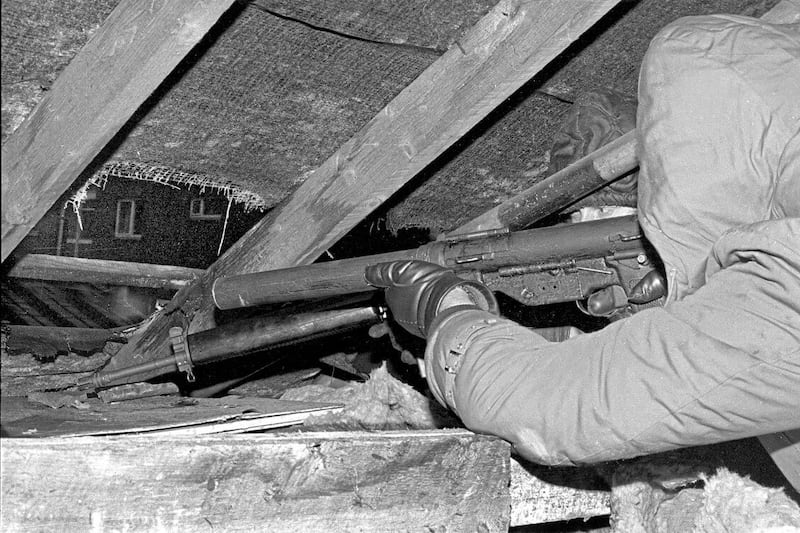

That’s not justice. Scappaticci's unique role inside the IRA gave the British access to information at the heart of the organisation – including its active service units.

Details of every volunteer he engaged with in his role in the IRA’s internal security unit (often after planned attacks failed) was passed to his handlers.

No wonder the British referred to him as their ‘golden egg’.

There was no way his secrets were ever going to make it into a court of law.

When former Sinn Féin press adviser Danny Morrison had his conviction quashed, his lawyers were even denied access to Ministry of Defence (MoD) documents.

Scappaticci's lawyers in all his legal dealings in civil cases over the past 20 years were hired by the UK MoD.

His role was embarrassing for the Provisional IRA. The organisation’s abject failure to regularly change the personnel in its internal security unit (aka the Nutting Squad) was a fatal error.

But his role is potentially much more embarrassing for the British. Scappaticci has been wrongly referred to as an ‘IRA killer’.

He was in fact a British State murderer, Maggie Thatcher’s very own assassin.

Operation Kenova has linked him to 15 murders.

Up to 30 people were killed and branded as informers by the IRA during the time Scappaticci was working for the British, with a number of them later cleared of working as agents following post-ceasefire investigations by the Provisionals.

Some of the victims of the Nutting Squad were agents of the RUC and other security force branches.

RUC Special Branch handlers of west Belfast estate agent Joe Fenton (killed by Scappaticci in 1989) were angered at his demise at the hands of another agent of the British State.

Agents call themselves agents. They are variously called ‘informers’ and ‘touts’ by others.

What surprised me was their handlers also referred to them as ‘touts’ in their source reports. Fenton and Scappaticci were both referred to as ‘touts’ in some of the reports I have seen.

The MoD and the British establishment will be relieved Scappaticci is dead.

They can now bury his secrets too. Victims will never see the one million pages generated by Operation Kenova.

The UK Government proposal for an ‘Independent Commission for Reconciliation and Information Recovery’ may, one day, do so.

But I wouldn’t hold my breath.

What I do know is that without whistleblowers like Martin Ingram (who co-authored our book Stakeknife), Scappattici would still be living in west Belfast and no-one would have been any the wiser about this whole dirty affair.

Ingram paid a high personal price for speaking out. Among other things, he had his computer hacked and personal information stolen.

Should the Tories succeed in bringing in its murder amnesty, families of victims will need a lot more whistleblowers to come forward if they ever want anything remotely near the truth. But they can forget about ever getting justice.

* Greg Harkin is a journalist and author of Stakeknife: Britain’s Secret Agents in Ireland