Drugs that treat HIV are being trialled for the first time in people with multiple brain tumours, for which there is no current cure.

Scientists believe the already-approved medicines ritonavir and lopinavir could shrink tumours in people with neurofibromatosis 2 (NF2), a genetic condition which causes tumours to grow along nerves.

While usually non-cancerous, NF2 can cause symptoms such as loss of balance, hearing loss that gradually gets worse over time and ringing in the ears.

If tumours grow inside the brain or spinal cord or along the nerves of the arms and legs, people can suffer limb weakness and persistent headaches.

The new clinical trial on 12 people, led by Professor Oliver Hanemann at the Brain Tumour Research Centre of Excellence at the University of Plymouth, will build on lab studies showing the HIV and Aids drugs can slow down and shrink NF2 tumours.

Previous research has also shown promise in using the drugs for other types of brain tumour.

There are no current treatments for NF2, which affects about one in 25,000 to 40,000 people, other than surgery.

Prof Hanemann said: “This could be the first step towards a systemic treatment for tumours related to NF2, both for patients who have inherited NF2 and developed multiple tumours, as well as patients who have a one-off NF2 mutation and have developed a tumour as a result.

“If results are positive and the research develops into a larger clinical trial, it would be the most significant change for patients with this condition, for whom there is no effective treatment.”

During the year-long trial, patients will undergo a tumour biopsy and blood test before having 30 days of treatment with the two medicines.

They will then have another biopsy and blood test to see whether the drugs have managed to enter tumour cells and shrink the tumours.

Dr Karen Noble, director of research, policy and innovation at Brain Tumour Research, said: “What is great about using repurposed drugs such as ritonavir and lopinavir is that they have already been shown to have a strong safety profile in healthy people and those treated for HIV, which means that they can more quickly be translated from the laboratory to patients.”

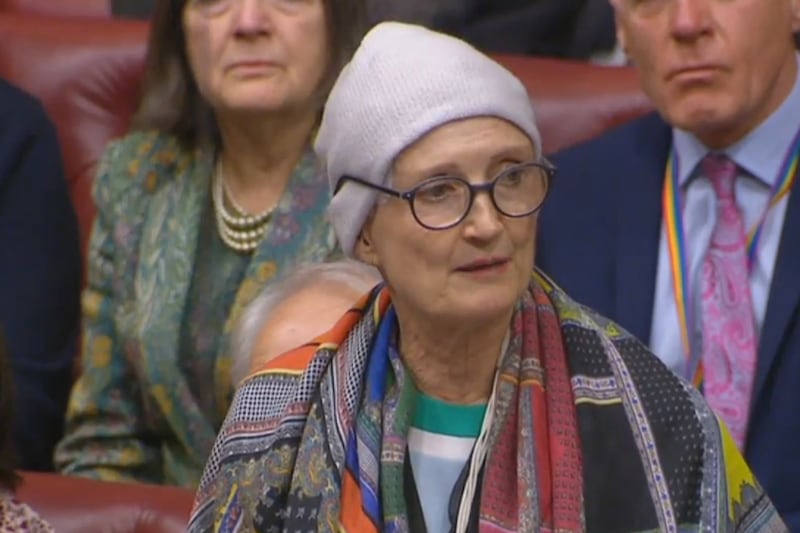

Jayne Sweeney, 57, from Mevagissey, Cornwall, was diagnosed with NF2 in 1996.

She has 12 tumours growing in her brain and has had five operations to remove tumours from her brain, ear and ankle.

Mrs Sweeney said: “The Retreat trial is incredibly exciting – any advancement to improve people’s lives is brilliant.

“A cure for NF2 is too late for me, but I am extremely proud to have been invited on to the trial steering group where I have seen first-hand just how passionate the team is about helping people with this disease.

“If we can find an effective drug for people newly diagnosed, that would be fantastic.

“For me, the loss of hearing is the worst thing about having NF2 because it’s very isolating and frustrating.”

Mrs Sweeney has undergone 15 months of chemotherapy and Gamma Knife surgery, with painful injections into her head.

“Finding better and kinder ways to treat the disease is so important,” she said.

In half of all cases of NF2, the faulty gene is passed from a parent to their child.

If either the mother or father has the faulty gene, there is a 50% chance that each child they have will develop NF2.

In other cases, the faulty gene appears to develop spontaneously but it is not known why this happens.

Most people with NF2 eventually develop significant hearing loss and the condition worsens over time.