ON the occasion of the death of someone who has lived so long, with such strength and so fruitfully as Canon Brendan McGee, sorrow and joy are inseparable companions: thanksgiving for such a life; sadness at its completion.

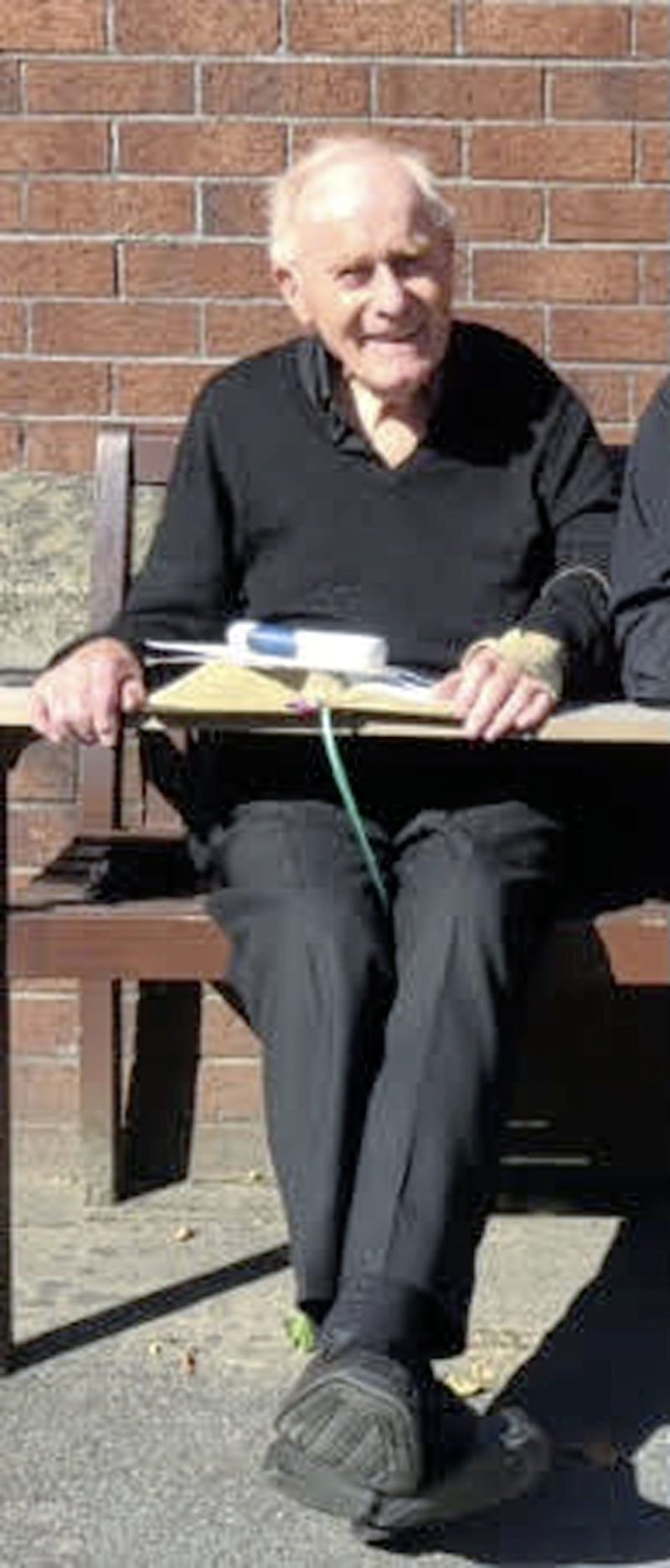

Until recently Dean of the Cathedral Chapter and the most senior priest in Down and Connor by age and ordination, Brendan – who died aged 96 on February 9 - wore his eminence lightly.

As Bishop Noel Treanor said at his Requiem, he was a “social justice” priest of the old school – pursued all his life by a sense of fairness, straight dealing and the practical consequences of the Gospel.

Ordained in 1950 and sent first to Dunmurry, where post-war Catholics were feeling confident enough to venture, he abhorred the petty discrimination of the Stormont regime which starved his parishioners of housing and burdened them with humiliating restrictions on schools and never-ending fundraising.

Refusing to be cowed, Brendan founded St Anne’s Primary School and, for over a decade, bridged the shortfall in state funding with a committee which sent out 40,000 begging letters annually throughout Ireland, Britain and the United States: the 3 per cent return rate was enough to keep the school alive.

Later, with the same energy, he chaired the Down and Connor Housing Association which built more than 400 houses for the needy.

His was a life throughout its many decades accompanied by the love of family, the consolation of deep friendships and the daily satisfaction of knowing that he was doing something that he loved.

Brendan loved to evoke the idyll of his rural childhood in west Tyrone. It had formed his mind and heart.

One of his revered uncles was a doctor who, drafted into the army during the war, chose to stay with those left behind in the desert of North Africa upon Rommel’s advance and become a prisoner of war rather than leave the wounded without care.

He never forgot this example of self-sacrifice and faithfulness to a higher duty.

Brendan was a man whose life was defined by service – spending himself in each of his parishes; always giving his best and fullest energies; never answering anything but “yes” to the next challenge; and choosing to spend his retirement in the inner city.

His longest service in a parish was in St Patrick’s, Donegall Street, Belfast, at an age when most people would be spending their days with their feet up.

And here, I had the great privilege of witnessing his power to heal – in conversation and confessional; his superb judgement in every issue; his light-hearted capacity to see the fun even in the most intractable situations and human foibles.

His flinty, oft-quoted, perspective-giving wit – always followed by the infectious laugh that was his trademark.

Once, when asked for his reaction to being promoted from Archdeacon to Dean of Down and Connor, Brendan returned the impish quip: “Six fewer letters to engrave on my gravestone!”

Even in his mellow years, Brendan’s scalpel-sharp anecdotes distilled wisdom into aphorisms without ever seeming self-conscious.

He often quoted a remark made to him by the late Monsignor Mullally by whom he had been summoned: “Some priests do nothing and are therefore never wrong. Other priests do many things; and half the time they are wrong: but half the time they are right.”

Brendan took this as absolution – and permission to experiment.

In a recent interview for a history of Vatican II, he astonished the academic interviewer with the acuity of his insights.

He was imbued with a love for the Scripture. He had first visited the Holy Land in 1957, where he had coffee with King Hussein of Jordan. He visited many times subsequently, exploring the land of the Bible on his own by bus, bicycle and on foot. He could evoke the landscape of the Gospels as if it were film, and he constantly sought direction in his life and ministry from this daily contact.

It was a comfort to us all just to watch Brendan say his prayers in St Patrick’s each morning and evening. His mystical sense of the Divine in the midst of the everyday world was luminous. His presence, his prayer, his humility – a rock of stability.

On that last day he spent in St Patrick’s Presbytery after 19 vigorous years, Brendan took time to say farewell to a seminary student working temporarily in the parish office.

On hearing of his death, he sent me the words spoken to him: “You know I’m so lucky God called me to be a priest. I feel very fulfilled as I come near to the end - even if I am nearly baked! Imagine being able to say I offered the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass and forgave sins. I’ve been able to hold God in my hands every day. It that’s not fulfilled then I don’t know what is.”

Thank you Brendan for your life and your kindness. You lived with vigour and died with hope. May those who have gone before you welcome you – the children you baptised, the penitents you absolved, the grieving you calmed, the dying you comforted, the homeless you housed – may they welcome you joyfully to your reward.

Fr Eugene O'Neill