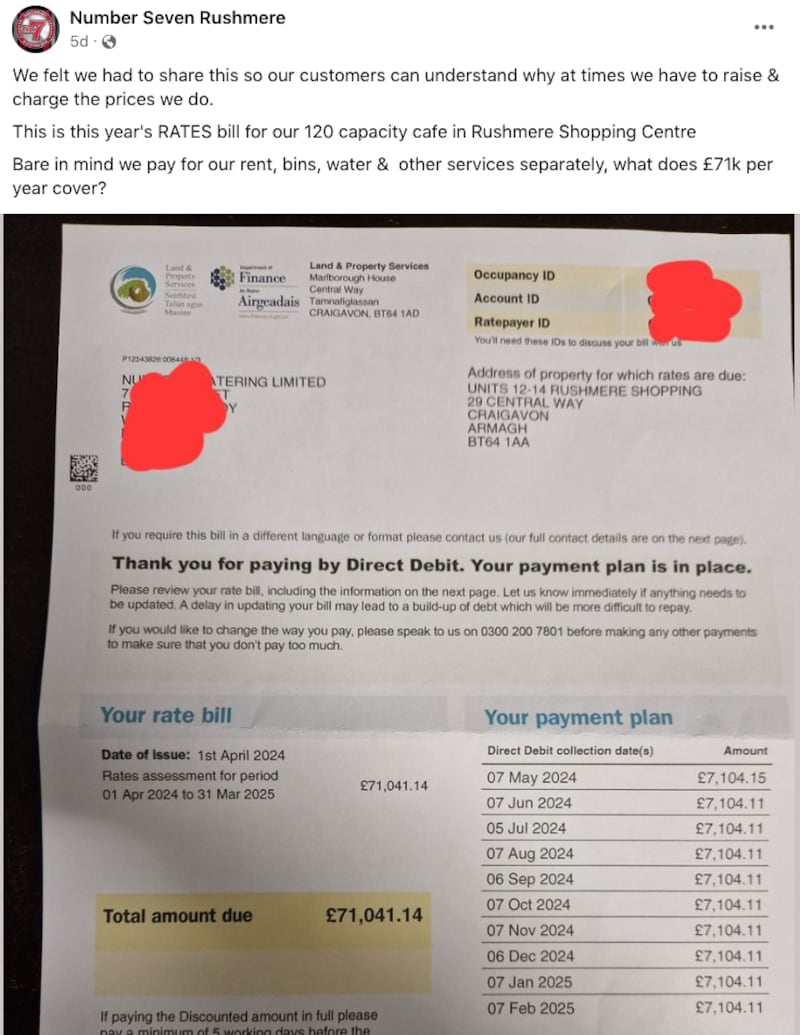

The Number 7 cafe in Craigavon’s Rushmere Centre – an institution in the town – has made headlines by publicising its £71,000 rates bill for the coming year.

Bringing this issue to public attention is important because bamboozling the public is why business rates, properly called non-domestic rates, have been pushed up to damaging levels.

Stormont and the councils have a furtive, populist policy of loading more of the rates burden onto businesses in order to freeze domestic rates for householders.

Yet the public ends up paying business rates anyway, through higher prices in shops and the wider costs of urban decay. Employees in the over-taxed sectors face lower wages, fewer opportunities and a greater risk of losing their jobs. It is a cynical false economy.

Stormont and the councils receive roughly £1.3 billion a year in domestic and business rates, getting about half the revenue each.

Since the DUP and Sinn Féin took over in 2007, Stormont has largely frozen domestic rates while sharply raising business rates. The NIO has taken the opposite approach during collapses of devolution but this has not been enough to reverse the trend. Councils have done much the same and their trend has never been interrupted.

As a result, the share of total rates paid by businesses has increased over the past two decades from a half to two-thirds. Nor is the share on businesses evenly spread. It has been loaded onto retail and hospitality by exemptions for others.

Although shops of all types represent a quarter of business premises by rateable value, they pay a third of business rates. Town centre shops are 16 per cent by value yet pay a quarter of rates.

Reform of the system has been on the agenda, only to fall foul of events. There were detailed reviews of business rates in 2016 and 2019, plus a revenue-raising consultation on all rates in January this year. Most of this work has been disrupted by stop-start devolution and the pandemic, but the reports are still sitting in Stormont’s in-tray, full of options ministers could pursue.

The most obvious would be scrapping the 50 per cent discount for vacant premises, effectively a subsidy for dereliction, which cost £43 million in 2016 (stop-start devolution has meant reviews using rather old figures). Britain abolished similar discounts in 2008. Doing so here is a no-brainer, despite the protestations of some commercial landlords.

The most expensive exemption is for charities, costing £96m in 2016. Churches and sports facilities were about half this bill, with charity shops £5m. All are considered politically untouchable but scope remains to reduce the charities exemption by a useful amount. For perspective, the much-discussed cap on domestic rates for expensive houses costs £9 million a year.

The next-largest exemption is industrial de-rating, which cost £71m last year, mainly through a 70 per cent discount for factories. This is unique to Northern Ireland, supports jobs and investment and is said by some firms to be more important than cutting corporation tax. Nevertheless, it is recognised as too broadly targeted and major savings could be made. A separate discount scheme for small businesses costs £17m a year.

Agricultural land and buildings are exempt from rates, while farmhouses get a 20 per cent discount. No calculation of the lost revenue has been made because farms have not been valued for rates in modern times but the potential is presumably vast.

Stormont subsidises farmers from its own budget, so it might consider charging them rates to be robbing Peter to pay Paul. However, the main reason such rates are not considered is that farmers would scream blue murder. Intriguing options to raise money and manage land use are thus missed.

The public consultation for the 2019 report asked for ideas to widen the tax base.

Stormont and the councils have a furtive, populist policy of loading more of the rates burden onto businesses in order to freeze domestic rates for householders

Suggestions included a derelict land tax and a land value tax, which in theory could be implemented through business rates, although it would require a degree of innovation Stormont has never shown.

A more realistic suggestion came from a retail and hospitality business in Dungannon, which wanted a clearer duty on councils to reduce costs and justify how rates are spent.

Perhaps there is no need for even that level of transparency. All the public has to know is that our elected representatives think we will scream blue murder if domestic rates go up by a few pounds a week, so they are killing our town centres instead.