NEWS of the death of Bob Moses, a pioneer of the US civil rights movement in the 1960s, brought back memories of how much he and his friends set an example to campaigners for equality and justice in Northern Ireland.

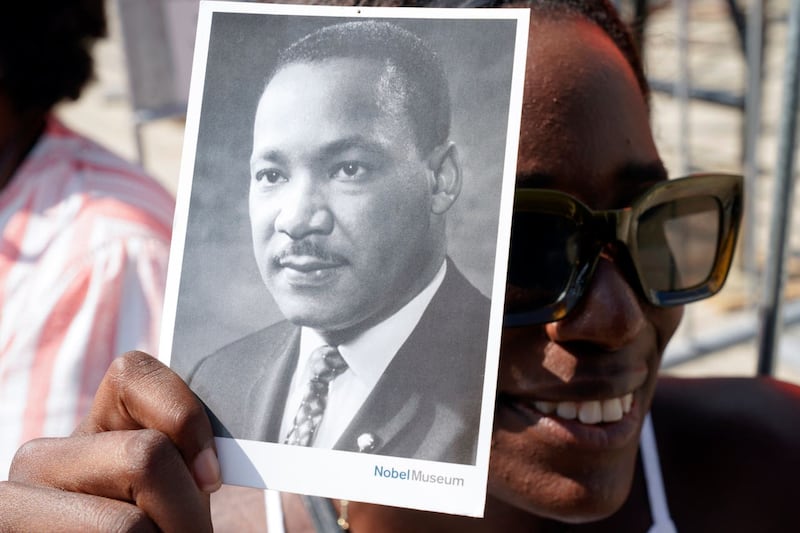

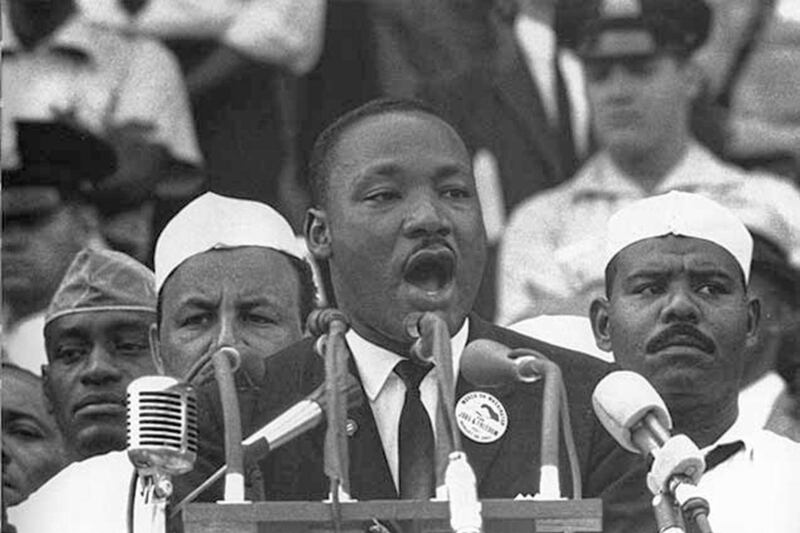

Many young people were inspired by the likes of himself and particularly Martin Luther King who delivered the famous “I have a dream” speech at the Lincoln Memorial in Washington DC to an estimated 250,000 demonstrators demanding civil and economic rights for African Americans.

In that oration, delivered on August 28 1963, Dr King recalled how, 100 years previously at the height of the Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation that all persons held as slaves in the Confederate states “henceforward shall be free”.

Dr King pointed out that, all those years later, the lives of African-Americans were “still sadly crippled by the manacles of segregation and the chains of discrimination”.

He went on to use his famous “I have a dream” phrase, not once but eight times in all. He dreamt, for example, that his own “four little children” (the youngest born exactly five months beforehand) would “one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the colour of their skin but by the content of their character”.

That speech still motivates campaigners for equality throughout the world. The civil rights movement in the north was based on the American model, down to the use of We Shall Overcome as its theme-song.

Indeed, Dr King ends his oration with the hope that not only black and white people but also “Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics” would one day “join hands and sing in the words of the old Negro spiritual: Free at last! Free at last! Thank God Almighty, we are free at last!”

Two years after his Emancipation Proclamation, Abraham Lincoln was shot in the back of the head at Ford’s Theatre in Washington.

I visited the location some years ago and also the room in the nearby Petersen House where the wounded president was taken and died the next morning. It was a moving experience to see the humble circumstances in which a person of such honour and distinction met his end.

Just over a century later, in April 1968, Martin Luther King himself was shot dead in Memphis, Tennessee.

Regarding the Irish context, I recently watched the DVD documentary We Shall Overcome, commissioned by the Civil Rights 1968 Commemoration Committee for the 40th anniversary in 2008 of the movement’s emergence on the streets of the north. In an interview, John Hume recalled: ‘We were very heavily inspired at that point of time by the [US] civil rights movement and the Martin Luther Kings of this world.”

There was a turning-point of course on January 4 1969 when the People’s Democracy Belfast-Derry march (modelled on the Selma-Montgomery marches in the US) was attacked by at least 200 loyalists with planks, bottles, crowbars and cudgels at Burntollet Bridge.

Some see it as the start of the Troubles and in Are You With Me (The Lilliput Press, 2020) a biography of the late Kevin Boyle, one of the march leaders, author Mike Chinoy quotes him as saying years later that the Belfast-Derry march was a mistake: “If we’d known the results, to go ahead couldn’t have been justified.”

Interestingly, former head of the Northern Ireland Civil Service, Sir Kenneth Bloomfield, wrote in his book A Tragedy of Errors (Liverpool University Press, 2007) that he and his colleagues mistakenly drafted a statement issued by the north’s Prime Minister Terence O’Neill which condemned the march as “a foolhardy and irresponsible undertaking” when the PM should have been expressing contempt for “loyalist thugs who had assaulted this smaller number of young people” who, despite irresponsible conduct and questionable motivation, were entitled to pass along a public road in safety.

In Bloomfield’s considered view, that statement seriously undermined the growing support in some nationalist quarters for O’Neill and his administration.

Hindsight is 20/20 vision and the Troubles might very well have erupted even if the Belfast-Derry march was called off or if Captain O’Neill had made loyalists the main focus of condemnation.

But despite the current problems, whether relating to the Protocol or the past or whatever, I still have a dream that, in Dr King’s words, “the jangling discords” can one day be transformed into “a beautiful symphony”. Let freedom ring!