The concept of fake news is not new. It did not start spewing from a golden toilet in Manhattan, although the capacity of Donald Trump to lie almost every time he opens his mouth is quite staggering.

His election win in 2016 emboldened others all over the world to follow suit and relegate the truth to the margins. It has made the world far more dangerous and nastier, and should he win again in the coming weeks, it could be an extinction-like event for democracy.

The annus horribilis of 2016 was also the year of the Brexit vote. The campaign to leave the EU is remembered chiefly for its lies. The lie emblazoned over a big red bus suggesting that the NHS would get an extra £350 million a week is the one that stands out. Many more lies were told then and subsequently, including about Ireland and the border on the island.

There are many similarities between the Brexit campaign and the controversy over the Boundary Commission in the 1920s, and how they were played out in the media.

While the media landscape was far less sophisticated in the 1920s, the use of propaganda tools to spread misinformation and denigrate opponents was as potent then as it is now. The British media was deployed to diminish the nationalist case for the transfer of large parts of Northern Ireland to the Irish Free State, particularly in 1924 when the boundary question showed signs of engulfing British party politics in crisis over the Irish question yet again.

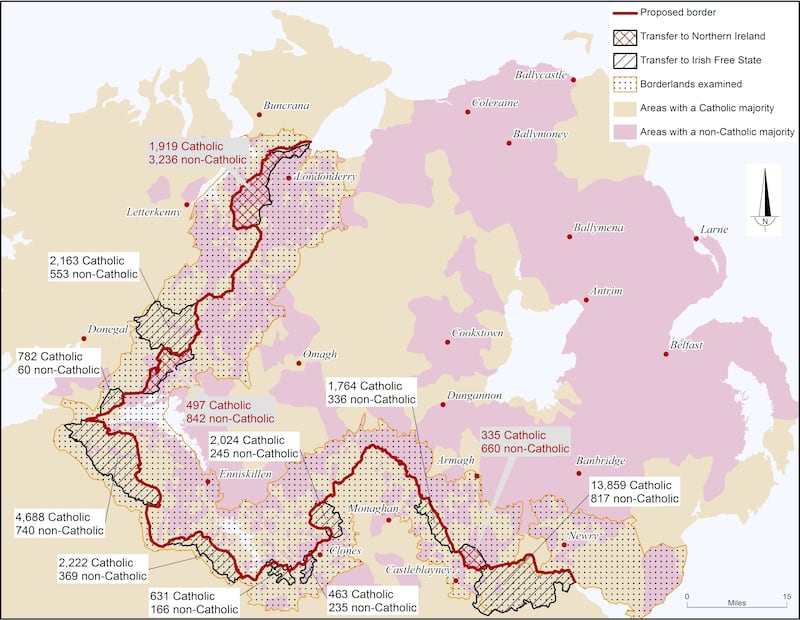

The Boundary Commission was a key component of the Anglo-Irish Treaty signed in December 1921. It still had not convened, however, by 1924. While the Irish Civil War and instability in British politics contributed to its delay, the northern government’s refusal to recognise the commission was the primary reason for the hold-up.

There was a general consensus among the British political parties that the optimal solution would be for the Boundary Commission not to meet at all, but if it was to convene, its recommendations would be so slight that it would not jeopardise the territorial integrity of Northern Ireland.

But while some in the Conservative Party were happy to break an international agreement – the Treaty – perhaps in a “specific and limited way”, its leader Stanley Baldwin believed it could open the door for an Irish republic and bring even more difficulties to his door.

With WT Cosgrave’s Free State government insisting that the Boundary Commission must meet and James Craig’s Northern Ireland government equally insisting it must not, Craig, helped by key British political figures and the right-wing press, conducted a media campaign throughout much of 1924 aimed at destroying all the main arguments put forward by the Dublin administration and northern nationalists.

This was achieved by false claims that Ulster unionists were promised by the British government in 1920 that the six counties included in Northern Ireland under the Government of Ireland Act 1920 was a final settlement, and by equally vociferous claims that the British signatories of the 1921 Treaty only envisaged small rectifications through the Boundary Commission with the full knowledge of the Sinn Féin signatories at the time.

Hugh A MacCartan was responsible for the publicity department of the North-Eastern Boundary Bureau, whose job was to make the case for Irish nationalism at the Boundary Commission. He complained to his colleague Bolton C Waller about the “reckless propaganda” from the British press, saying it “would require one man and one typist working full speed to reply to all the misstatements in the provincial press alone”. He intended to publish “a weekly summary of misstatements entitled ‘Fallacies of the Week’, giving the misstatement and the reply in each case”.

MacCartan recognised the “great advantage” the Belfast government had with the Conservative papers who were “definitely committed to the ‘Ulster’ attitude and are very influential, whereas the Liberal papers have not yet had a clear lead from the party and will not face this handicap and do what we can in spite of it”.

He thought that “the Liberal papers incline towards the ‘rectifying’ view. I doubt very much whether any party in England will enthusiastically adopt our larger view”.

Cosgrave railed against the English press for treating the Free State government as unreasonable and Craig as “the white-haired boy”.

In newspapers like the Morning Post and Daily Mail and Belfast-based papers like the Northern Whig, stark and sensationalist headlines were used throughout 1924 to paint the Free State as a place full of extremists and the demands of Ulster unionists to be reasonable and just.

Punch magazine portrayed the typical Irishman as an ape-like figure in contrast to the stoical, strong Ulsterman. Craig wrote an article in The Spectator claiming that “Ulster” was as British as Lancashire. The 1921 Treaty was referred to as the “surrender Treaty” and the six counties “the irreducible minimum”.

By the time the Boundary Commission finally met for the first time in November 1924, so intense was the propaganda campaign that the accepted orthodoxy throughout Britain was that there could only be small changes, and that the “extreme” claims for the Free State to take Tyrone and Fermanagh were fantastical and would never be entertained.

Given this background, it was always unlikely for the British-appointed members of the Boundary Commission, Justice Richard Feetham and Joseph R Fisher, to do anything but tinker with the border, which is precisely what they recommended.

While the wording of the Boundary Commission clause was at the root of most of the subsequent problems nationalists encountered, the intensive media campaign of 1924, largely based on falsehoods, was decisive in shaping the boundary question as one of rectification rather than substantial surgery.

Fake news existed 100 years ago as it does today and can still come from many different sources.

The most worrying factor from today’s perspective is the power of social media which, to date, has escaped many of the regulations and libel laws more traditional forms of media face, allowing those platforms to spread lies and misinformation with little or no consequence.

The erosion of democracy will continue at pace until this elephant in the room is addressed.