Given the enormous shift in social attitudes, it takes some doing to lose two referendum votes on an issue most people agree with. But in this uncertain world, you can be sure of one thing: if the current Irish government can mess things up, it will.

An ability to make a pig’s ear out of a silk purse is one of the defining characteristics of the coalition. It did that big-time at the weekend when the electorate effectively gave a vote of no confidence in the Republic’s political class.

Yes, it happened on Leo Varadkar’s watch, and he must take his fair share of the blame. But all the major parties endorsed the changes – designed to rid the constitution of language which diminishes the role of women and relationships outside marriage.

It could have been different. Clearer drafting of the changes, answers to meet concerns, and a positive campaign that engaged the electorate, might have seen a better outcome. But the electorate wasn’t convinced that there would not be unintended consequences, and decided the status quo was the lesser of two evils.

The next government, of whatever complexion, will have to address these issues again. De Valera’s constitution – flawed by the Catholic hierarchy’s overt influence – hobbled Ireland then. The flaws which remain must be addressed. Whenever the vote comes, the government will need to make a better job of the campaign.

Referendums are a blunt instrument, as history has shown. These results would be less worrying if they did not point to a much more fundamental problem with this hapless administration – namely its inability to read the writing on the wall and plan for the future.

That can most clearly be seen in the Irish government’s failure to prepare for the inevitable vote on Irish unity. We don’t yet know when it will come, but we know it is coming.

Speaking after his referendum humiliation, Varadkar said: “It was our responsibility to convince the majority of people to vote ‘yes’ and we clearly failed to do so.”

If the Irish government continues to manage its northern policy in the way it has done to date, he (or, more likely, a future taoiseach) will be using the same form of words after a border poll.

From what can be seen, little or no progress has been made on framing the debate on a unity poll which makes the benefits – economic, social and cultural – clear.

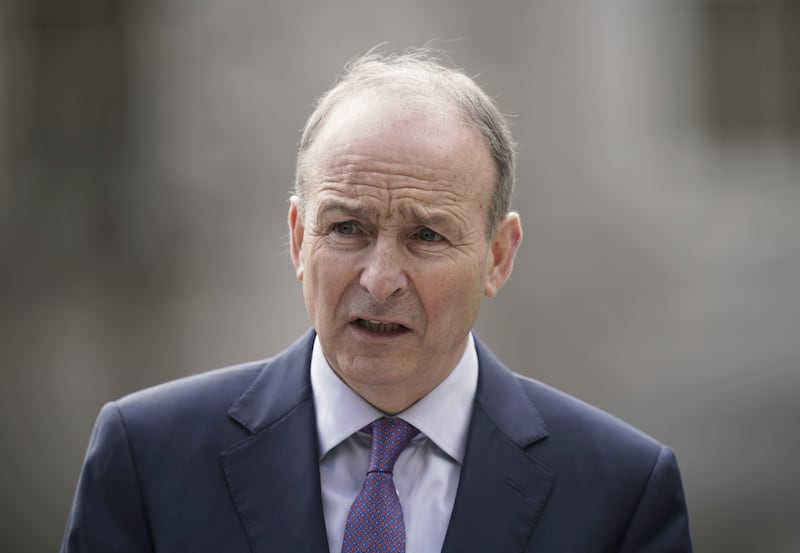

We are at one of those all too familiar points in Irish history when an inept and disinterested British administration is looking across at its mirror image in Leinster House. While unity should be a policy imperative, neither of the main parties in the south has dedicated the energy needed to achieve it. As taoiseach, Micheál Martin was as useless as Varadkar.

With the British economy in freefall, and fatally undermined by Brexit, the economic case for Irish unity has never been stronger. But more than that, it is clear there has been a cultural shift in the north – and it is not just the change in the demographic balance between Catholics and Protestants.

Without evidence, voters will revert to the status quo. Varadkar and Martin need to get the finger out

Many young men and women from a unionist background see through the smoke and mirrors of Orange politics, and want to build better lives for themselves in a democracy that is connected globally, not disengaged from the world.

A border poll will be won on the middle ground – soft nationalists and soft unionists. The type of people likely to be freaked out in the privacy of a polling booth by the fear of unintended consequences.

It is the responsibility of the Irish government to prepare the ground and to be explicit about what unity means – politically, economically, socially and culturally. Promises of a brighter future must be underwritten by hard evidence. Facts, figures, the fine details.

Without evidence, voters will revert to the status quo. Varadkar and Martin need to get the finger out.