It is generally agreed that we should speak only good of the dead, but in the case of General Frank Kitson who died last week, some might be prepared to make an exception.

Kitson is best known for supervising repression, torture and killings and while that made him a military hero to some, he might more accurately be remembered as the sting in the tail of the dying wasp that was the British Empire.

Most commentary on his passing tended to portray him as some form of maverick soldier. Even his obituary in the London Times said that no general “has provoked more intense and sustained controversy”.

However, the truth is that Kitson did not act alone. Everything he did had political approval, as subsequently evidenced by his collection of ‘honours’. These included the Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the British Empire (which many might regard as a dishonour) and becoming the Queen’s Aide-de-Camp (a sort of upper-class domestic help).

We know what he was associated with here: the creation of the military reaction force, internment, the torture of the hooded men, the Ballymurphy massacre, Bloody Sunday (he complained that not more had been shot) and the use of widespread military disinformation, including false claims that the McGurk’s bar explosion was the work of republicans.

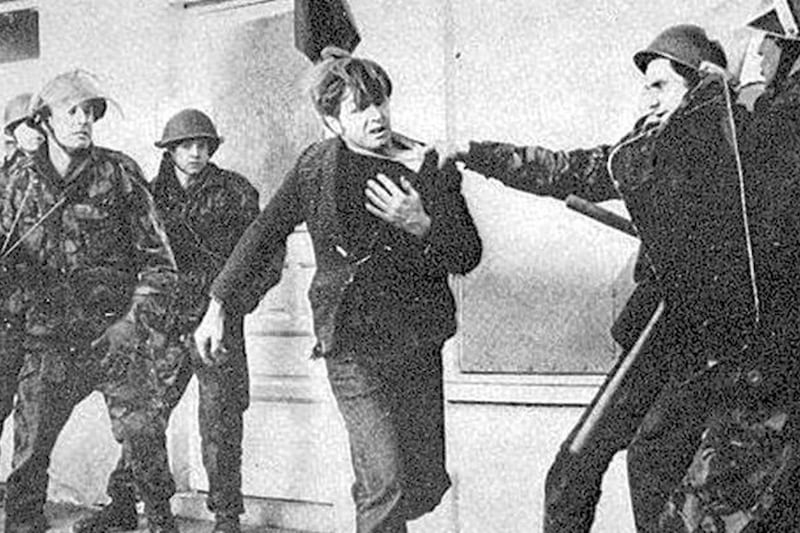

He did not have a particularly high public profile when he arrived here, so when I helped to produce, They Came in the Morning, the first detailed account of internment, we put his photograph on the front cover.

He had published Low Intensity Operations the previous year, which effectively advocated anti-civilian terror. (He predicted that the wars in Vietnam and the north would be over within five years. He was right about Vietnam.)

However, to portray Kitson as a mere soldier is to miss his true purpose. He served in Malaya, Bahrain, Cyprus and Aden, but Kenya best explains his function.

The truth is that Kitson did not act alone. Everything he did had political approval, as subsequently evidenced by his collection of ‘honours’. These included the Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the British Empire (which many might regard as a dishonour) and becoming the Queen’s Aide-de-Camp (a sort of upper-class domestic help)

The 1884 Berlin conference divided most of Africa between major European states. Britain claimed part of east Africa which became Kenya, without any reference to the 40 tribes who lived there. (The Turkana and the Samburu tribes did not even know they were in Kenya until after the British left.)

In pre-colonial Kenya, tribes adapted their agriculture to the local ecology for the collective good rather than individual wealth. However, British settlers exploited Kenya’s natural resources, forcing native farmers onto infertile land and making them work on European-owned farms and plantations.

The Master and Servant Act (1920) enabled white settlers to exploit the Kenyan population by criminalising any disobedience, making it punishable with prison or hard labour. When Kitson arrived there as an intelligence officer in 1953 he later remembered “the strangeness” of seeing so many black people.

When the Mau Mau rebelled against injustice, the British interned one million people in what were effectively concentration camps and confined another half million to their villages. It was a tale of systematic violence and high-level cover-ups.

So Kitson was actively involved in the destruction of a people’s culture, beliefs, economic activity, social structure, values and behaviour. Today the UK is the largest European foreign investor in Kenya, through about 100 investment companies, valued at more than £2 billion. The country has 970 precious minerals.

Less than 0.1% of the population (8,300 people) now own more wealth than the bottom 99.9% (44 million people) – a far cry from pre-colonial times. This illustrates the long-term consequences of what Kitson and his political masters did across the globe.

Their impact also lives on here. In his 1960 book, Gangs and Counter Gangs, Kitson described how to exploit tribal rivalries by supporting one side against the other. We know which one he supported here.

His advocacy of unrepentant and arrogant colonialism is currently reflected in the secretary of state’s refusal to meet the reasonable pay demands of public sector workers here.

You see, Kitson may be dead, but we are still living with his legacy.