In the autumn of 1925, Irish Free State president of the Executive Council, WT Cosgrave, directed government departments to produce memoranda highlighting the main implications of territory potentially being transferred from Northern Ireland.

With the Boundary Commission’s award imminent, the British and Free State governments wanted to arrange for as smooth a transition as possible.

While the commission’s award and its report would ultimately be shelved, with the border remaining unchanged, the preparatory work highlights the importance of considering the many changes that might occur when territories undergo constitutional change – something that everyone who is contemplating such change in Ireland soon needs to bear in mind.

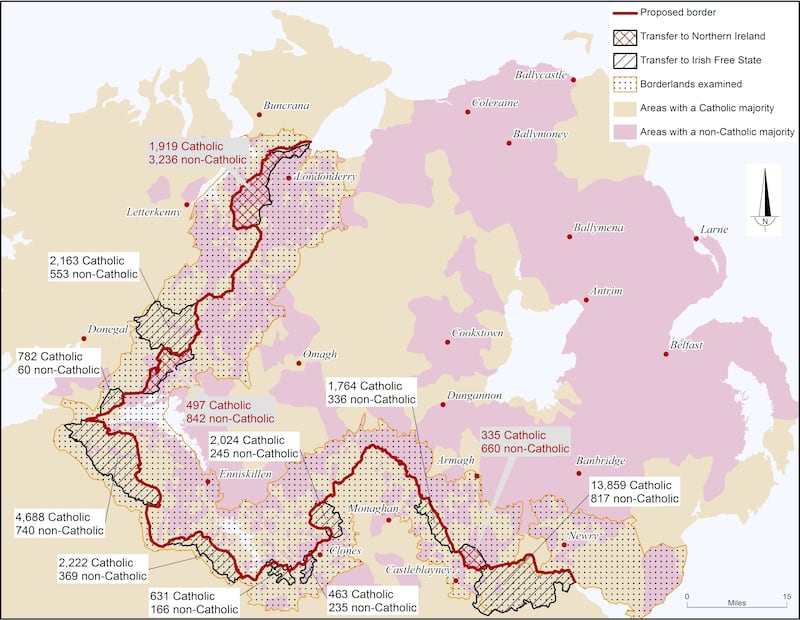

Under Article 12 of the 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty, the boundary of Northern Ireland was to be determined by a Boundary Commission. No legislation was required, nor was any period of transition recommended between the announcement of an award and its enactment.

Fearing the dangers of the border being changed without prior notice, the British and Irish Free State governments met in London in July 1925 to discuss the arrangements they could collectively make for the required changes across multiple departments, and the need for a transitional period from announcement to enforcement.

It was proposed that the “first essential was the preservation of law and order, and the administration of summary jurisdiction; next the postal services; then the fiscal services; and finally the principles on which officials were to be dealt with”.

The Free State Justice Minister, Kevin O’Higgins, saw no difficulty in gardaí replacing the RUC in transferred barracks. However, B and C-Specials resident in areas transferred to the Free State would have to abide by the Free State law on possession of firearms. He recommended that they be disarmed by either the northern or British governments during the transition period.

The Free State Army chief of staff, Peadar MacMahon, insisted that it must be prepared for three eventualities: a peaceful transition without any disturbances; acceptance by the northern government but armed conflict with inhabitants of transferred territory; or the refusal of the northern government to accept the Boundary Commission findings.

MacMahon declared: “Should the third eventuality materialise, unless the British step in and force the commission’s findings, then war must be the inevitable result.”

In June 1924, the British Army general staff had envisaged that three divisions and a cavalry brigade would be needed “to control an organized Ulster Unionist opposition”.

In a memorandum to the northern cabinet, Home Affairs minister Richard Dawson Bates warned in August 1924 of the artillery and aircraft superiority of the Free State army who, according to his intel, had 11 aeroplanes as opposed to none being possessed by the northern government. He stated: “Even a single bombing aeroplane can do a great amount of damage, which we have no means of preventing.”

Most departments who replied to Cosgrave’s request were less apocalyptic in their answers than MacMahon, with some, such as the Department of External Affairs, claiming that no changes were required at all on its part.

The Department of Agriculture envisaged that little change was required for legislation enacted before partition, but for 1924 Acts such as The Agricultural Produce (Eggs) Act and the Dairy Produce Act, “some legal instrument would appear to be necessary before they could be made to relate to added areas”.

Eoin MacNeill’s Department of Education did not envisage any serious difficulty in assuming control of transferred services but did want to know beforehand if the northern government would facilitate the transfer of records and documents of the schools affected. In the likely probability of it not cooperating, experienced inspectors would have to visit the schools and procure the information needed.

Transferred teachers were expected to be subjected to the 10 per cent salary reduction in operation at the time in the Free State. Initially, teachers’ word on what their salary was would suffice, “subject to adjustment when the necessary verification had been obtained”.

For the Department of Finance, customs barriers posed the biggest challenge with the transfer of territory. Customs stations and boundary posts would have to be uprooted, if possible, and moved to the new boundary line. Arrangements with railways and on approved roads would have to be changed, as would all the supplementary notifications.

The changes imposed on staff, all public sector employees, including their housing, needed to be considered as well as the disposal or examining of goods in transit.

The rates for old-age pensioners would require adjustment in accordance with the provisions of the Free State Old Age Pensions Act 1924. As with teachers, if the northern government did not help with the transfer, “it would be necessary to obtain fresh claims from pensioners and to investigate each case de novo”.

Unemployment Insurance at the time was paid as an uncovenanted benefit in Northern Ireland while in the Free State the unemployed only received benefits covered by contributions. A danger was envisaged that some people who were receiving unemployment benefit in the north would immediately become penniless once transferred to the Free State, unless some special provision was made such as relief grants or employment schemes.

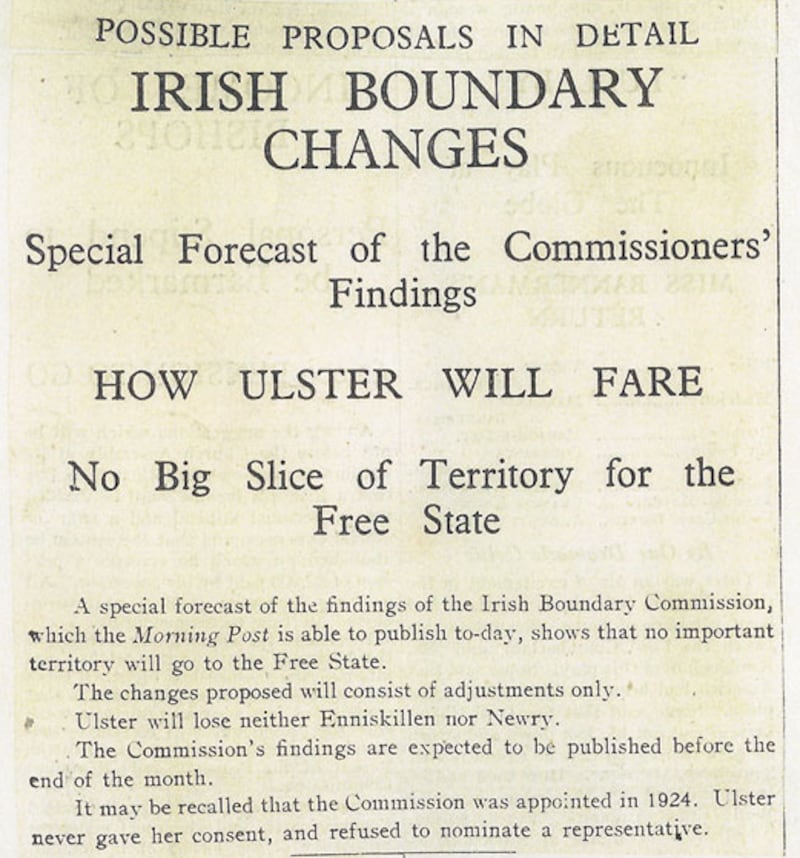

As it transpired, none of the changes were required as the border remained unaltered due to the collapse of the Boundary Commission later in 1925. It does provide, though, some examples of how the two Irish jurisdictions had diverged in just four years after Ireland was partitioned.

Now, more than 100 years since partition, naturally the challenges of constitutional change will be of a far greater scale and depth.

It is imperative on all who desire a united Ireland to prepare fully for the comprehensive changes likely to occur in multiple facets of life and society, should the people of Northern Ireland vote for unity.

Most importantly, as Leo Varadkar advocated at an Ireland’s Future event in June in Belfast, the next Irish government needs to actively works towards a united Ireland “to prepare the ground for it”. The scale of the change involved demands it.

Home Affairs minister Richard Dawson Bates warned of the artillery and aircraft superiority of the Free State army who, according to his intel, had 11 aeroplanes as opposed to none being possessed by the northern government. He stated: ‘Even a single bombing aeroplane can do a great amount of damage, which we have no means of preventing’