After the North-South Ministerial Council meeting on Monday, Leo Varadkar’s last political event as taoiseach, he emerged and gave an interview in which he said he was “confident that the institutions [of the Good Friday Agreement] are stable and will be sustainable”. The two are not the same.

The institutions are sustainable because they’re well devised and designed, but they’re not stable. Indeed, in his next sentence Varadkar revealed his concerns about possible destabilising events.

He said: “Events happen in politics, whether it’s changes in leadership, there’ll be elections for the House of Commons, there’ll be elections for the Dáil all within the next year, and what’s really important is that institutions should be able to function through them and withstand any disruption that may occur.”

- Red, white and blue command paper seeks to restore unionist veto at Stormont – Brian FeeneyOpens in new window

- Simon Harris’s waffle on Irish unity shows he couldn’t care less about the north – Brian FeeneyOpens in new window

- Collapse of Stormont and the powersharing Executive: An explainerOpens in new window

He was correct. There’s potential for serious disruption because of election campaigns and because of the elections themselves and their outcomes. The indisputable fact is that this artificial British creation is inherently unstable and will remain so.

The north is not unique in that respect. Belgium, another artificial creation, is also an inherently unstable place, divided between Flemings and Walloons, with growing numbers of Flemings not accepting Belgium as a state and demanding independence. The place has been more or less in permanent constitutional crisis since 2007. It holds the world record for running without a government: first, 541 days after the 2010 elections, then beating that record when the government collapsed in 2018 with 652 days.

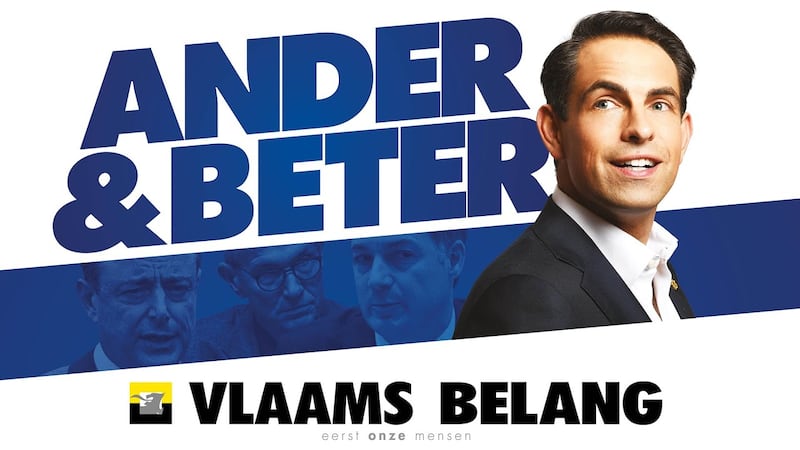

Now there is the prospect of an even bigger crisis after elections which are due in June. The far-right Vlaams Belang party which says Belgium doesn’t work, and certainly not for Flemings, wants an independent Flanders. It’s now the biggest political force in the state. Its ranks have been swelled by opponents of immigration which, as in in other European countries, has become a major problem.

The Vlaams Belang, allied with the second largest Flemish party, hopes to win June’s elections and control the government, compelling the Walloon (French-speaking) parties to negotiate independence. However, the Walloon parties won’t turn up to such negotiations. And then…? Any of this sound familiar?

There may be similarities with the north, but there are important differences which should make the Stormont administration more sustainable. For a start, we have only two major parties, who have seen off their politico-ethnic rivals. In Belgium there was a five-party coalition which collapsed in 2010 and in 2020 a seven-party coalition emerged, each coalition composed of differing factions of Flemings and Walloons and a German minority party. Talk about herding cats.

Compared with that the power-sharing executive here should be child’s play but nevertheless, it’s precarious. The immediate threat is the developing internal civil war in unionism becoming poisonous around the prospect of pacts and splitting the unionist vote.

The TUV/Reform deal threatens DUP safe seats in the upcoming British general election. The DUP election manifesto will need to deploy as much smoke and as many mirrors as the British ‘Safeguarding the Union’ paper, but will still not manage to satisfy the TUV whose leader threatens to stand candidates against anyone implementing what he calls (correctly) the ‘Donaldson deal’. The outcome remains to be seen.

The indisputable fact is that this artificial British creation is inherently unstable and will remain so

Be that as it may, the main difference between political crises here and those in Belgium is that Belgium is an independent sovereign state with no external mitigation, whereas this place is the decaying remnant of England’s first colony, still governed from London but critically with input from Dublin.

The prospects of events such as Varadkar described destabilising the GFA’s institutions is real, but the lesson for avoiding that is closer cooperation between Dublin and London in running this place.

The blame for much of the disruption and destabilisation in the last 14 years can be laid at the door of the British government which breached the ‘rigorous impartiality’ obligation of the GFA and consorted with the DUP. Secondly, the British government deliberately and wilfully excluded the Irish government from critical decisions affecting politics here, particularly since 2016.

Varadkar and the EU ran rings round the British on Brexit, but the treacherous British solo run with their DUP dupes did profound political and societal damage here.