It was 40 years ago – a lifetime, and yet almost every detail is still crystal clear.

April 12 1984. The phone in the hall at my parents’ home was ringing in the darkness. It wasn’t yet 3am, but the sound woke me with a start. A phone ringing at that time of the morning was only ever going to be bad news.

I ran downstairs and picked up the receiver to hear my aunt Margaret say: “Your Auntie Peggy’s been killed in a bomb at their house. Wake your mammy and tell her.”

To this day I regret how I broke that terrible news. I rushed into my parents’ bedroom, waking them from their sleep, shouting: “Auntie Peggy’s dead. There was a bomb…”

In the next few moments, I went into automatic pilot. I’d been doing reporting shifts at The Irish Times office in Belfast, and one of the duties was to ring the police press office every hour until midnight to check if there’d been any “incidents”.

I rang, and June, the press officer who answered, didn’t query the fact that it was hours after after the normal time for calls. “There was a bomb attack on a house in University Street. Two fatalities at the scene, a 52-year-old woman and a police officer.”

A UVF murder gang had left a bomb in a hold-all on the window sill at the front of their house. Peggy spotted it on her way in from working as a part-time taxi driver. The police were called, but somehow didn’t see it and rang the doorbell.

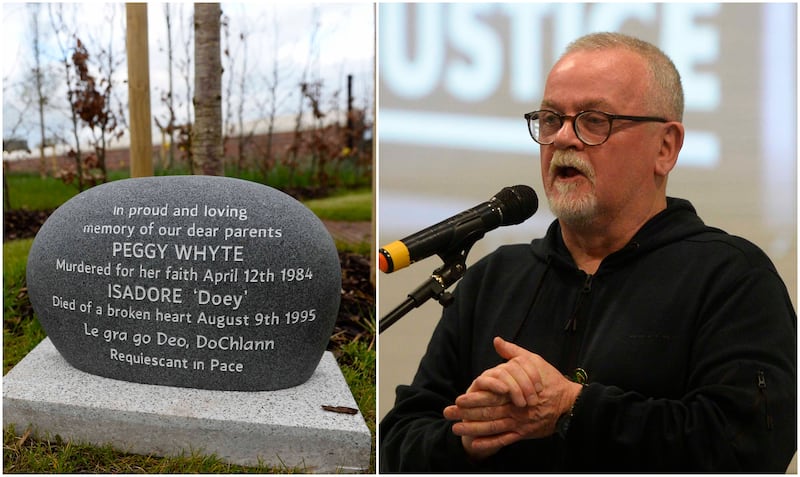

The bomb went off as Peggy opened the door, killing her and the young police constable, Michael Dawson, instantly.

The attack by the UVF came just a few days after the IRA shot dead 22-year-old teacher Mary Travers in a gun attack on her father, the magistrate Tom Travers, who was seriously wounded.

They’d been on their way back from Sunday Mass at St Brigid’s on Derryvolgie Avenue, on April 8.

My mum was in the choir there and they sang at Mary’s funeral the following Wednesday. In the small world that is Northern Ireland, Constable Dawson had been on duty, only the day before, sitting guard outside the ICU where the magistrate was seriously ill.

Peggy, my mum’s youngest sister, was a red-headed bundle of energy and laughter. A mother-of-ten, she’d found a new lease of life after passing her driving test and taking up part-time taxi-ing.

She used to regale us with tales of the “ladies of the night” that she often picked up, listening to their stories and always anxious that they got home all right. “They have a hard life,” she would say.

It wasn’t the first time her home had been attacked. Just a year earlier, a young loyalist man lost an arm and a leg when a bomb he’d planted at the back of the house exploded prematurely.

At that time, Peggy ran outside and put a pillow under the injured man’s head while they waited for an ambulance, whispering prayers into his ear.

Her son, Jude, remembered the young man saying, “Mister, don’t kill me” when they ran to his assistance.

Why was the family targeted? They were a large family of mainly boys and they were frequently harassed by UDR patrols in the area.

In the days of “nods and winks” in the wrong quarters, they were identified as “republicans”. In the first Press Association bulletin that went out immediately after her killing, Peggy was described as “believed to be republican”.

I ran downstairs and picked up the receiver to hear my aunt Margaret say: “Your Auntie Peggy’s been killed in a bomb at their house. Wake your mammy and tell her”

My brother, also a journalist, rang a colleague who worked for PA who told him the information had come from the cops.

- Northern Ireland Lower Ormeau Catholics were among the most targeted during The Troubles, says son of UVF murder victimOpens in new window

- Kingsmill families ‘treated with utter contempt’ says victims campaignerOpens in new window

- Victims campaigner Jude Whyte appalled by Shankill Butchers memorialOpens in new window

She was actually a member of the Alliance Party. But nods and winks were good enough to get you killed back then.

Being simply Protestant was enough to get the workmen at Kingsmills killed too.