WHEN you’ve been at it as long as Patsy McAllister, another four or five months isn’t anything to get excited about. In boxing as in life, it’s all about patience - so long as the job gets done, and done right, that’s all that matters.

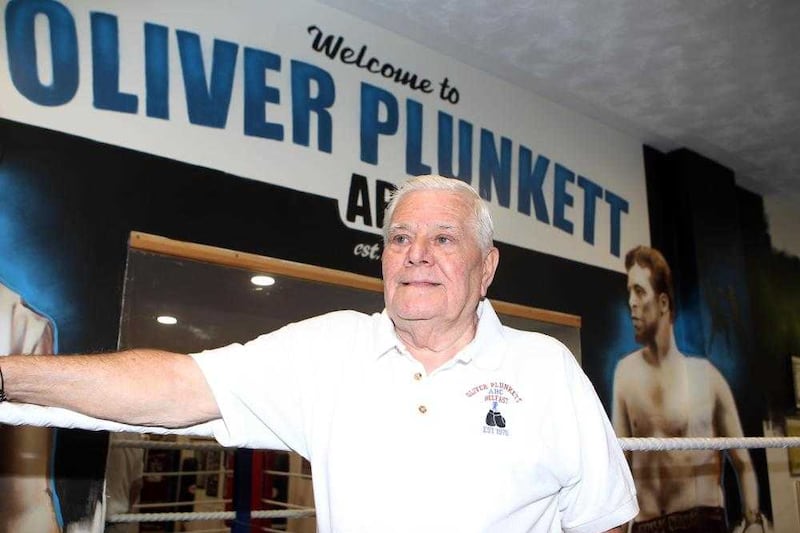

Standing in the middle of the newly-refurbished Oliver Plunkett boxing club last Saturday afternoon, surrounded by young kids, proud parents, old friends and new, the man who first opened its doors was in his element.

“They were working on it the last four or five months, but it’s finished now," he said.

“We got a grant from Sport NI and we were able to get a new sign, murals, two shower rooms, changing rooms, new lighting, new flooring, gas heating, new doors and windows, the outside of the club tarmaced, spotlighting… A friend of the club took away all the pictures and posters and got them framed. Look at it now, the place is in great order.”

A new lick of paint may have given Patsy McAllister a new lease of life but, with his 80th birthday just around the corner, it has also led him to reflect on his own journey. From sparring his father in the living room of their Sailortown home to picking up the pieces twice after previous club buildings were razed to the ground, to all the hope that today inspires, there are memories at every turn.

The eldest of 15 - nine brothers and six sisters - McAllister believes he was destined for a life in boxing after an early introduction to the fight game through his father. One of Patsy’s earliest memories is sitting outside the ropes at the old Jack Robinson gym in the Market area of Belfast (it would later become St George’s ABC) while his father did his business in the ring.

Despite being christened Gerry McAllister, his father fought under the moniker Patsy Quinn during a 16-year, 64-fight career. The only people who knew him as Gerry were his work-mates down at the docks and his mother.

Indeed, that’s the very reason he took an assumed name. Only 15 when he made his professional debut in 1933, Gerry McAllister didn’t want her to find out he was trading leather for pay: “His mother would’ve killed him - she didn’t want him fighting at all,” laughs Patsy.

“There was an old flyweight champion, Jackie Quinn, who lived around the corner from us. Jackie had a brother called Patsy who died young, so that’s where the name came from. Even until he died, people would’ve always known him as Patsy Quinn.”

Patsy McAllister, meanwhile, was 13 when his father eventually hung up the gloves and, by then, boxing had taken a firm grip: “I used to spar my father in the living room in the house - the only rule was I couldn’t hit him,” he says.

Bringing down the curtain on his own fleeting career in the ring at just 18-years-old, McAllister’s own calling was as a coach. Having learned his trade at the Dominic Savio club before it was disbanded, McAllister and Jimmy Finnegan opened the first incarnation of Oliver Plunkett in Hannahstown in 1970.

It was short-lived, however, with an early morning knock on the door coming as the rudest of awakenings just two years after the club was formed: “At three in the morning, Jimmy [Finnegan] came down and woke me up to tell me the club had been burnt to the ground. We lost everything.

“I don’t want to accuse anybody, but we had a certain boxer at the time - God rest him, he’s dead now - who was very fond of a cigarette after training so, rightly or wrongly, we always put it down to him,” recalls McAllister with a smile.

Like a phoenix from the flames though, the club rose again, a wooden hen house at the bottom of Hannahstown hill the next place to be called home. There Oliver Plunkett remained until 1992 when, on July 4, came another knock at the door.

“Patsy, the club’s on fire,” informed the bearer of bad news.

McAllister takes up the story: “I went down and the firemen were standing looking at it.

“I said to one: ‘are you not going to do anything here?’ He said ‘what’s the sense? Let it burn’. It was an old timber structure, we couldn’t even insure it.”

Undimmed by such rotten luck, McAllister rallied the troops and started again from scratch. Not once did the thought of throwing in the towel cross his mind. The third - and hopefully final - incarnation of the club opened at South Link in west Belfast a year after its second untimely demise.

“I sent out begging letters everywhere,” explained McAllister.

“We got good support from the people I knew - I couldn’t say I had good support from the community as a whole. Nothing, to be quite honest. As a matter of fact, there’s people who live around here who don’t even know the boxing club’s there. That’s the truth.”

With or without them though, McAllister, along with fellow coaches and comrades Jimmy McGrath and Eamonn Finnegan, has made it work. Throughout the years, the club has produced some top quality boxers, the likes of Christy Carleton, Anthony Cacace and cruiserweight hope Tommy McCarthy just some of those to have passed through his hands.

The official reopening last Saturday was vindication for all their efforts and, in the case of Patsy McAllister, reward for a life dedicated to the sport: “I’m still in the club every night, I’d miss it if I didn’t have it. Sure, what else would I be doing? It’s my life. My father and my family all boxed, my brothers boxed, my sons boxed.

“I’m lucky that I have great people around me. Being honest, I’m very selective in picking people who come into the gym. I like people I know I can depend on and trust. We’re a family-oriented club, when you look at the Finnegans, the Deeds, the Youngs, all families who have come through the club. It was always just like that.

“I’ve great faith in men like Jimmy. You couldn’t ask for better men to work alongside. But the final word still rests with me.”