ON a typically frenetic morning at Belfast City Airport, Ray Close does a double take as he peers through the crowd of bodies criss-crossing the arrivals hall.

The moment passes in a millisecond as reality kicks in. There are some men on this earth of whom there can be no mistaking, and Christopher Livingstone Eubank is one of them.

It’s early 2012 and the former world super-middleweight champion is in town on business. His son, Chris junior, is preparing for the third fight of a fledgling pro career on the undercard of Tyson Fury’s Odyssey Arena showdown with Martin Rogan.

Close may no longer boast the welt of jet black hair from his fighting pomp but recognition is instantaneous as he emerges from the masses.

Back in the early ’90s Close and Eubank shared a ring for 24 gruelling rounds at packed halls in Glasgow and Belfast. On this morning they share a hug, a handshake and a few minutes of reminiscence as the world carries on about its business.

It is the first time they have laid eyes upon each other since the late 1994 press conference to announce the third, potentially most lucrative instalment of the series – a fight that never happened after Close failed a brain scan.

Rough, tough Dubliner Steve Collins stepped into the breach on a famous night in Millstreet the following summer and the rest, as they say, is history.

Eubank lost that fight, the first defeat of his career, but had further money-spinning outings against Collins again, the up-and-coming Joe Calzaghe and big-hitting Carl Thompson at cruiserweight.

Sat alongside earlier epic duels with Nigel Benn and Michael Watson, his body of work stands up to the closest scrutiny. The snarling, the sneering, the posturing and preening, it was all part of the show and when the curtain finally came down, it did so on his terms.

The same could not be said for Close.

Eubank was the golden ticket he had been waiting for to propel himself into the world title mix. Yet when he finally got there in his mid-20s, it was snatched away in the blink of an eye.

Banned from boxing in Britain, his career fizzled out with five low-key fights in America as dreams of another world title crack, another shot at the big time, faded from view before he last laced up gloves in 1997.

Close started working at the City airport a year later and remains there to this day, helping passengers with mobility difficulties; happy and healthy with the same unassuming disposition that placed him, in personality terms at least, on a different stratosphere to his most famed opponent.

The old foes press flesh one final time before setting off in different directions. Almost two decades had passed then since their first meeting, now stretched to a quarter of a century, and all that remains are moments frozen in time and the memories of two nights when David thought he had slayed Goliath.

***************************************

THE pause lasts just six seconds but feels like an eternity. Very quickly you learn that Chris Eubank is not a man to be rushed.

“Hmmmm,” comes the low response on the other end of the line before another short spell of silence, “underestimated would be the wrong word.”

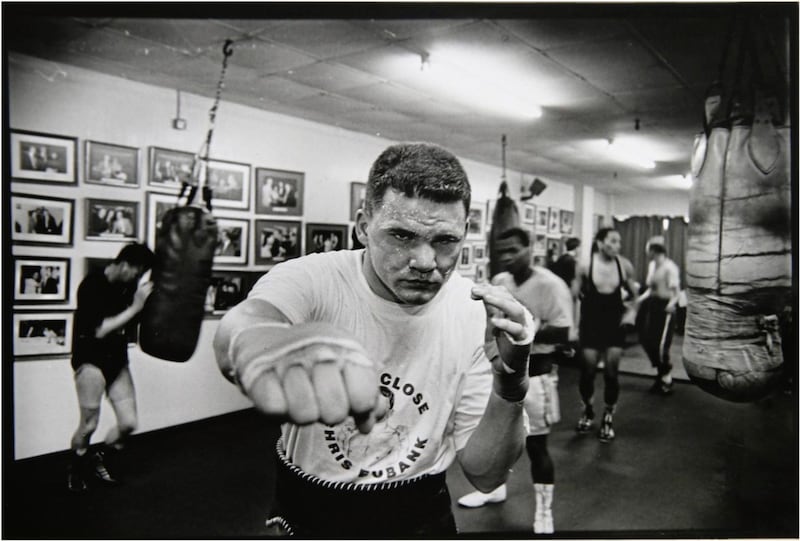

With 35 wins from 35 fights, a curious aura surrounded Eubank by the time he agreed to defend his WBO crown against Ray Close in May 1993.

Curious because Eubank wasn’t so good that you could never see him being beaten. This wasn’t Sugar Ray Leonard bamboozling opponents with speed of hand and thought, nor was it a young Mike Tyson steamrolling one man after the other.

But, somehow, Eubank always, always found a way to win.

“He was a hard bastard.”

This is the matter-of-fact appraisal of Ronnie Davies, the trainer who was with Eubank through the main stretch of his career and, at 72, still works the corner of Chris junior.

“The old man could fight. He came up hard. You couldn’t hurt him, he would walk through anything.”

Davies well remembers the day Senior first strode into his gym having returned to England from New York in 1988, a raw but robust 22-year-old, charisma bursting from the seams.

“He walked in, started training and said ‘I like you Mr Davies, I’m going to give you a three month trial’.

“Three month trial?! F**king cheek. But it just went from there…”

By the time they were preparing for Close five years later, the pair were on exactly the same wavelength, even if the frequency had to be dialled in every now and then.

The first meeting with the unheralded east Belfast man in Glasgow was viewed with cynicism. In some quarters it was seen as nothing more than a marking time fight for Eubank ahead of a much-anticipated rematch with Nigel Benn.

Not that the champion’s camp was taking anything for granted.

“Ray Close was a very, very good boxer and a top amateur before,” says Davies.

“I rated him very highly and anybody who didn’t, didn’t know their boxing.”

“I knew I had the beating of him,” says Eubank after careful consideration, “but here is a guy who was so much more than what he appeared.

“Ray had the beating of most men - they would under-estimate him because he was… what’s the word? Hmmm. Probably the word is ‘stealth’.

“He almost came to you as though he was invisible - ‘this guy’s going to be no problem’. But this is probably how he beat most other guys, because he was stealth.

“My thing was; I’m going to make you afraid of me in terms of the way I look. I’m going to look fierce. Sometimes I’m going to act vicious… not that I was,” he adds before breaking into a chuckle.

“I was always that person who gave you all the theatrics so people said ‘this guy looks the real deal in every department’, whereas Ray was like ‘oh well, y’know, this is the way I beat people’ - by making them think I’m not going to be there.”

***************************************

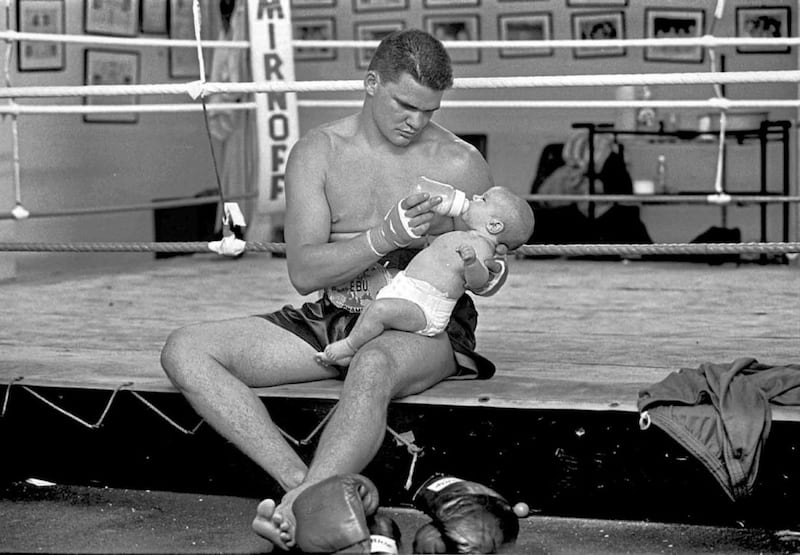

A SMALL rectangular frame hangs in the middle of a living room wall, the only visible reminder of a past life between the ropes. The photograph contained within is instantly recognisable, and remains as strikingly beautiful today as it was when Irish News photographer Brendan Murphy first clicked his camera all those years ago.

It shows Close sat on the ring apron at Eastwood’s Gym in Castle Lane, hand wraps still on, EBU European belt around his waist, staring lovingly into the eyes of baby daughter Sarah as he feeds her a bottle.

Once seen, never forgotten, it takes pride of place in their Bangor home.

“She was born one day and he went away to his training camp for the first Eubank fight the next day,” recalls wife Linda.

“We stayed in Beresford House down in Bangor, did all our runs around there and trained at Eastwood’s,” explains Ray, “and once you were in camp, you were in camp.

“So the next time I saw her was the day that photo was taken when she was five or six weeks old.”

Sarah - who would go on to follow her father into the ring, competing in the first-ever female bout at the Ulster Hall - is expecting her first child in December. Twenty-five years on, the couple smile at the timing.

Yet, had things been different, there might have been no Eubank fights to look back upon and celebrate.

After all, 10 months prior to Glasgow Close was stopped in his tracks by Frenchman Frank Nicotra eight rounds into his first challenge for the European strap – a second career defeat and one that threatened to derail any world title ambitions.

“That was a big learning curve for me. I just thought ‘I have to run more’,” he smiles.

“After five rounds I was spent. I had been doing well up to then, but these things happen. After that I started to run harder and longer, up the coast path, up to Crawfordsburn, Helen’s Bay, back and forwards.”

Promoter Barney Eastwood secured another crack at the EBU belt, now held by Vincenzo Nardiello, on St Patrick’s Day 1993 and this time the tank was fully loaded.

Close took a technical decision over the Italian after an accidental clash of heads brought the fight to a premature end in the 11th round. There was talk of a defence back in Belfast until Matchroom boxing chief Barry Hearn presented them with an offer they couldn’t refuse.

“I suppose ideally you’d have had a defence but when the world title chance came up we said ‘yeah, we’ll take that’.

“I only caught the tail end of Muhammad Ali’s career but he was my idol, and when I was young I said ‘I’m going to be heavyweight champion of the world too’ - I just needed to grow a few inches!

“But I had no reservations about fighting Eubank because it was always my goal, from I started out, to become a world champion like Muhammad Ali. And at that time I didn’t really rate him that highly. For me, he wasn’t a boxer.

“He had a good punch, and the reason he beat Nigel Benn was, although Benn had a big punch, he didn’t have a chin to go with it.

“Eubank had a great chin and a big punch, but other than that I thought he was quite one-dimensional.”

With only 59 days to prepare, it was out of one camp and straight into another. There may have been a new arrival on the way, but business was business and coming down the road was the fight of Ray Close’s life.

***************************************

THE plan drawn up by Bernardo Checa and John Breen was simple: establish the jab early, use your footwork, put the pressure on with quick, sharp combinations, then get the hell out of there.

Close felt relaxed. He had never been in a fight of this magnitude and while he wasn’t one for trash talk, he made sure to have a ready-made rhyme to counter Eubank’s press conference patter.

‘Chris, you’re good

Better than most,

But compared to Ray,

Nothing comes Close’

Outside of those few lines was the ‘stealth’ Eubank speaks of. Close gave him little else to work off and, as a member of the Church of the Latter Day Saints, instead placed his faith in the power of prayer moments before making his entrance at a raucous Scottish Exhibition Centre.

“I always said my prayers before I went into the ring, and a prayer for my opponent as well.

“There were nerves coming in but once you get in there, nerves leave you. Once you get a punch in the face you’re in it and away you go.

“I was a boxer and I think that’s the best way. I had a good jab and I was always told from my days at Holy Family, Ledley Hall, always start with the jab so I always led with my left hand.

“Everything else came from that.”

Using his fleet of foot and clever boxing brain, Close settled quickly. Soon it became clear that he was exactly the kind of man who could cause Eubank problems.

“He didn’t like them clever boys,” laughs Ronnie Davies, “he wanted them to come to him.”

“Light shots and light feet always troubled me because I always set myself to pivot with correct technique,” says Eubank.

“I was too correct for my own good, and Ray used the in-and-out game. I would have said him and a fellow called Dan Schommer were the best boxers I fought - skillsters, men who used their jabs, men who were not gung-ho.

“These are the guys who are very dangerous.”

Close ate up the early rounds, taking control heading into the second half.

Eubank, though, was never beaten. The championship rounds were always his; these were the moments when his grit and determination, that famous steel, would shine through.

Heading down the stretch he started to look the boss and, 59 seconds into the 11th, a brutal short uppercut on the ropes crumpled Close’s legs and left him on his backside.

Somehow he struggled to his feet to beat the count, even managing to win the last, but it was this shot that saved Eubank’s skin as the scorecards were read out.

London judge Dave Parris had Close three ahead despite the knockdown, Denmark’s Torben Hansen gave it to Eubank by four and Roy Francis scored it level, 115-115 - a split decision draw.

“The uppercut I hit him with travelled about three inches,” says Eubank.

“If I hadn’t scored that knockdown, Ray would have won that fight on points.”

So if underestimated was the wrong word, how does he reflect on a night when his unbeaten record almost disappeared against a man given little chance by most observers?

“Here was a guy who would always be ahead on points in fights because he was busy and he was technical in scoring those points and building. He knew he wasn’t a one-punch knockout artist.

“In that fight he would have been ahead on points because his workmanship was brilliant. So it’s not so much that I underestimated him, it’s that I knew I would catch up.”

“I think maybe I surprised him,” adds Close.

“If he hadn’t knocked me down, it wouldn’t have been a draw. It was the first fight he hadn’t won, and at the time that was unheard of. It was also the first time I’d gone 12 rounds.

“Everybody was telling me I’d won, but a draw is better than a loss. I was the first one to put a mark on his record and he’d been in with some great fighters, so I was happy enough.”

He was happier still as talk turned immediately to a rematch, and ecstatic when the King’s Hall was later confirmed as the venue. It may have been just over a year in the making but as the roof threatened to come off the iconic Belfast venue on May 21, 1994 you knew it had been worth the wait.

IN TOMORROW’S IRISH NEWS

“There was a very, very small man who threw glitter over me. It would have been known by the people within the game that we’ve got to find some way to disarm or discombobulate this man because he’s too solid. He’s too sure. We have to do something”

From Don King singing Danny Boy to leprechauns spraying glitter, don't miss part two as Neil Loughran looks back as an eventful fight week unfolded when Ray Close and Chris Eubank did it all again in Belfast