“Look at the stateeeeyaaaaat…”

CHRIS Eubank emerges from a white stretch limo outside the Europa Hotel, clad in brown knee-high riding boots with a monocle pressed to his right eye. A riding crop is tucked neatly into the nook of his arm.

As he makes his way towards the entrance, the sound of laughter echoes down Great Victoria Street as builders shout across scaffold on an otherwise quiet Tuesday lunchtime.

“Big man... big man... what time’s the next race?”

Eubank judiciously ignores their jibes but the message has been delivered, loud and clear: welcome to Belfast.

From Frampton to Burnett, McGuigan to McCullough, there have been some huge fight nights down the years. But a city synonymous with boxing has rarely, if ever, seen anything like the razzmatazz that surrounded the 1994 rematch between Eubank and home favourite Ray Close.

With Don King in town it was never likely to be anything but a circus.

The shock-haired American, a co-promoter on behalf of US network Showtime, was more than happy to assume the role of ringleader at the pre-fight press conference, eclipsing even the charismatic Eubank.

Close could only smile as King belted out a few bars of Danny Boy in that familiar booming bass before launching into a bizarre homily from his assumed pulpit.

“Ray the giant-killer,” announced the high priest of hype with a twinkle in his eye, “will muster up the Irish spirit of the shillelagh, the shamrock, the four-leaf clover and the dandelions jumping up in the field and going from glen to glen.”

“Between Eubank and Don King it’s a wonder I got a word in at all,” laughs Close 24 years on. “I enjoyed all that side of it. Anybody who says they don’t, they’re lying. That’s all part of it.”

And, just as he had done before their first meeting in Glasgow, the Belfast man took the wraps off his latest rhyme for the assembled media hordes.

“Chris says he’s the best but he’s simply the worst, and on Saturday night his bubble will burst.”

Predictably though, Eubank was never going to settle in the shade.

In a typical show of bravado he agreed a £1,000 bet, at odds of 66/1, with Close’s manager Barney Eastwood that he would stop his man inside the first round.

Headlines assured, the riding crop found its home once more as he strode through the revolving door and out into the mid-May sun.

The time for talking was now over; the real show was about to begin.

***************************************

‘Let me hear you say yeeeeaaaahhh!

No no, no no no no, no no no no,

No no there's no limit’

THERE was almost no distinction between the crowd and the fighter’s walkway as Ray Close travelled towards his date with destiny, the deafening sound of 2 Unlimited’s techno classic bouncing off every wall and back down from the steel roof.

If Don King’s hair didn’t already point to the sky, it surely would have by the time the Belfast man and Barney Eastwood negotiated their way through the charged, hyped masses.

“It was absolutely electric, that’s what I remember,” says Close, thinking back to that May 21 night.

“Coming in, see the noise… I was walking from my changing room and then you come in and the noise… that’s when the nerves kicked in.”

The decibel levels were cranked up further as the familiar strains of Simply The Best signalled Eubank’s arrival, a hail of boos and cat calls battling with Tina Turner for supremacy.

Republic of Ireland manager Jack Charlton, sucking on a huge cigar, leaned back in his front row seat, craning that long neck left and right as Eubank played up to his pantomime villain persona.

He slowed his step for dramatic effect before standing on the ring apron, snarling and sneering as men, women and children bayed for blood. The trademark hop over the ropes brought a lusty cheer from all four corners before a sharp shimmy gave way to a stand and stare moment.

Throughout his career Eubank had been no stranger to going behind enemy lines; every time, for those few minutes, he would feel completely at home.

“I was inspired by a few movies when I was a child.

“The Three Musketeers… in this particular one Michael York played D’Artagnan. If you think of that character, if you think of Charles Bronson’s character in the movie Once upon a time in the West.

“Going into that cauldron and being defiant, that was all inspired by Charles Bronson and Michael York. All these movies depicted an individual going into hostile environments so let me tell you, going to Belfast, it was beautiful.

“The Irish love a character, and who doesn’t adore defiance?”

Before a punch had been thrown in anger, however, the fight was held up for 11 minutes when Eubank found himself covered in glitter courtesy of a leprechaun-like figure spotted doing laps of the ring.

British Boxing Board of Control officials insisted every last bit of the offending material was removed before the fight could begin.

Matchroom boxing boss Barry Hearn fumed at ringside, but Eubank has his own suspicions about how, and why, the delay came about.

“There was a very, very small man who threw glitter over me,” he says, taking up the tale.

A leprechaun…

“Well I wasn’t going to call him that because leprechauns don’t exist, but very, very small men do.

“You know, the Irish are a very clever people. It would have been known by the people within the game that we’ve got to find some way to disarm or discombobulate this man because he’s too solid. He’s too sure. We have to do something.

“Now Steve Collins happened to find it a couple of years later in Millstreet, but at that time it was probably a very good idea to have a very, very small man throw glitter over me.”

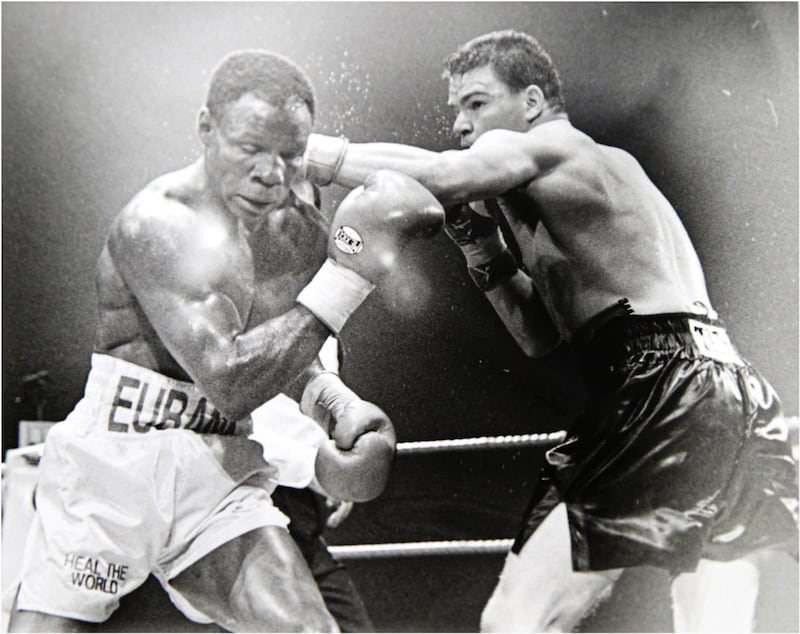

Whether by accident or design, the pause in proceedings did the home fighter no favours as Close struggled to find his feet in the early rounds.

The tension was simply too much for Linda Close who sought refuge backstage.

“In Glasgow I sat ringside and left. In Belfast I got into the seat, watched him walking in, then left.

“I was in the bathroom and had to keep hitting the blow-heaters – that’s all I can remember about Belfast because I could hear the crowd. It was awful. I just couldn’t cope.”

“I think I was lost in the atmosphere for a while,” says Ray, smiling at his wife’s recollection.

“It probably wasn’t until the fifth round where I started to find my accuracy, and I think that’s because I’d only had the one fight in 12 months. I could have been a bit sharper.

“But after the fifth round, I was taking over.”

The second half of the fight belonged largely to Close as he clawed back the rounds, although he had to survive a 10th round onslaught after a chopping right hand saw him desperately grasping for survival.

Somehow he managed to stay on his feet and, when the final bell eventually sounded, a nervous hush descended on the King’s Hall as the crowd caught its breath. Most thought Close had done enough, but then they thought that in Glasgow too.

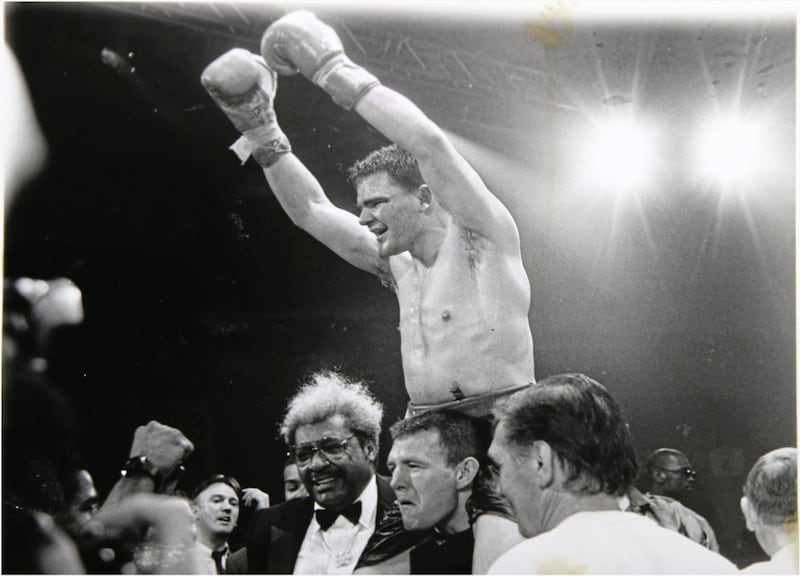

Don King hailed a new world champion, but the judges had other ideas.

They also had other ideas from each other, with Americans Gene Clark (118-112) and Clark Sammarino (115-114) both going for Eubank by varying margins, while England’s Roy Francis scored it 117-113 in Close’s favour.

Eubank had held on to his belt with a split decision win, but uproar followed revelations that the WBO-appointed supervisor had been unable to locate the master scorecard which tallied up the scores of the three judges as the fight progressed.

A furious Barney Eastwood called for an official inquiry and a WBO investigation. For the two men who had just slugged it out for 12 rounds, though, it remains a matter of debate to this day.

“I thought I’d won,” sighs Close, before Linda chips in: “I think everybody in the King’s Hall thought you’d won too.”

“Roy Francis was a judge at both fights - in the first fight he had it a draw, in the second fight he had me winning by three rounds. I thought that was about right. I thought Eubank only fought for one minute of each round.

“I have to say though, at the end of the fight, when it didn’t go my way, it could have turned ugly because the crowd thought I’d won it. I thought it might have got nasty but thankfully it didn’t.”

“I knew it was a very close fight,” says Eubank.

“The Irish rallying behind their man does have a way of concentrating your mind wonderfully on getting the job done, which is what I was trying to do.

“I can’t say that I had in my mind whether I’d done enough. If I lost a round, I lost it, but my job was always to complete a round being in front.

“Even if I hadn’t won a round on punches, I’d win it on foot movement and posturing, showing defiance to the crowd. I’d be a showman. So if I didn’t win physically, by theatrics I would win.”

WBO chief Nick Keriosotis insisted another rematch should be ordered immediately, and within weeks the wheels were in motion for a £2million trilogy fight back at the King’s Hall. That purse would have set Close up for life.

But when a routine MRI scan revealed the presence of two lesions on his brain, the British Boxing Board of Control revoked his licence.

All of a sudden his world was turned upside down, his world title dreams left in tatters.

***************************************

“WHEN I went to America I took all my scans from here, one every year, and they said those lesions had been present in my first scan in 1989. If they were there in my first scan, why did they pass me and then say I couldn’t box five years later?”

Ray Close sits forward on the sofa at his Bangor home as he asks the question, still vexed. The sense of frustration hasn’t dimmed almost a quarter of a century on as he recalls how the rug was ripped from under his dancing feet.

One minute Close was centre stage at one of the biggest fight nights his city had ever seen, the next he was going through the motions in Stateside outposts like Cicero, Dolton and Waukegen.

“It was difficult. I wasn’t making a lot of money. I was away from my family too, but that next world title shot was keeping me going.

"Hopefully then you’d see a bit of money and get back on track…”

Close was ringside in Millstreet in 1995 as Steve Collins ended Chris Eubank’s unbeaten record. On one hand he was delighted to see his old Eastwood’s Gym sparring partner do the business, but at the same time knew that elusive world title shot was drifting further and further away.

“I knew Steve Collins would never fight me.

“Before we were fighting for big titles, he was the Irish middleweight champion, I was the Irish super-middleweight champion and he always told me ‘I’ll never fight you’. We sparred lots and he knew I had the measure of him.

“I could’ve fought him in his home town, Dublin, because I had an Irish licence. But it was never going to happen.”

Post-Eubank, Close had five more fights in the US before the end came at the age of just 28. Talk of a comeback swirled around but never materialised.

Nowadays he is helping out at his old amateur club, Ledley Hall, but all these years later, what he wouldn’t give for one more fight. One more round even.

When boxing is in the blood, you can’t just flick a switch and forget.

“I’m still dealing with it,” he says with a rueful smile.

“If they gave me three months to train, to get back to 12 stone and get fit and sharp, I’d get back straight away. No problem.

“I’d love to box again. If you retire on your own merits, okay, but when you’re told ‘that’s it’, it’s harder to deal with. It was never my decision.

“But now I’m putting my energy into the boys up at Ledley and that helps a bit. Hopefully we can get a champion out of one of them.

“I enjoy it... my old trainer Herbie [Young] would’ve wanted me to do it.”

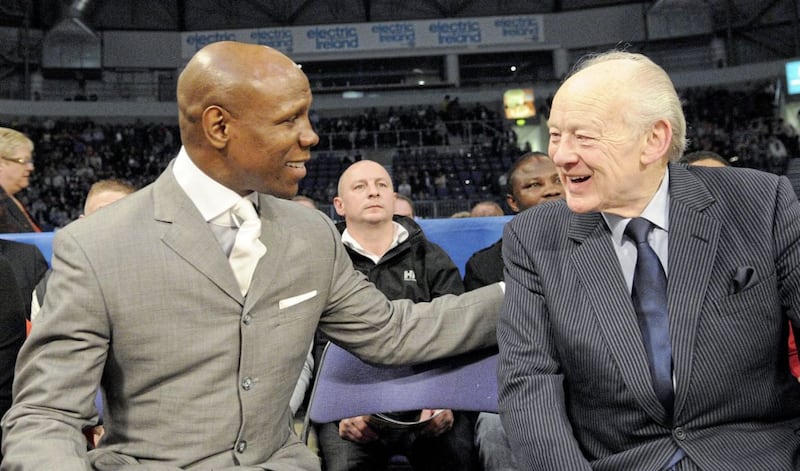

Eubank is still involved in the game too through his son, Chris junior, but doesn’t feel the same pull as Close.

“Boxing is a way of life, you can’t do it part-time.

“After fights I’d be back in the gym on the Monday. I didn’t club. I was ashamed to go into night-clubs, to wine bars, because I thought people would think ‘oh this guy’s a fake because real fighters don’t come into these places’.

“And you know, now looking back, nobody thinks like that. No-one. It’s a normal thing but it was so prevalent in my mind and this is the reason why… it may sound funny. It may sound nonsensical. But the reason I was back in the gym on the Monday is because I knew I wasn’t that good.

“That’s the reason I kept on winning – because I knew I wasn’t that good.”

Even in his 53rd year, however, he continues to be linked with a third showdown against old foe Nigel Benn. The temptation is always there but, for Eubank, sense has to prevail.

“They are still chasing me to fight him,” he laughs.

“Does it pull at me? Okay… of course it does but when you are using your intelligence, you are weighing things up and if you weigh them correctly, then you always do the sensible thing and the dignified thing.

“The great sages, the men of experience, they point these truths out. If we think of Desiderata [the 1927 prose poem by American writer Max Ehrmann], there is a line in it that goes as follows: ‘Take kindly the counsel of the years, gracefully surrendering the things of youth’.

“But wow… what a great time I had living the daydreams I had when I was a kid. It was beautiful. I didn’t like these times, I loved them.”