In the 1980s and ’90s, Barney Eastwood’s Belfast gym was one of the world’s most successful boxing stables. From it emerged a stream of world champions including Barry McGuigan, Dave Boy McAuley and Crisanto Espana. In the second chapter of his story, ‘BJ’ looks back at some great fight nights and one that got away. Andy Watters writes…

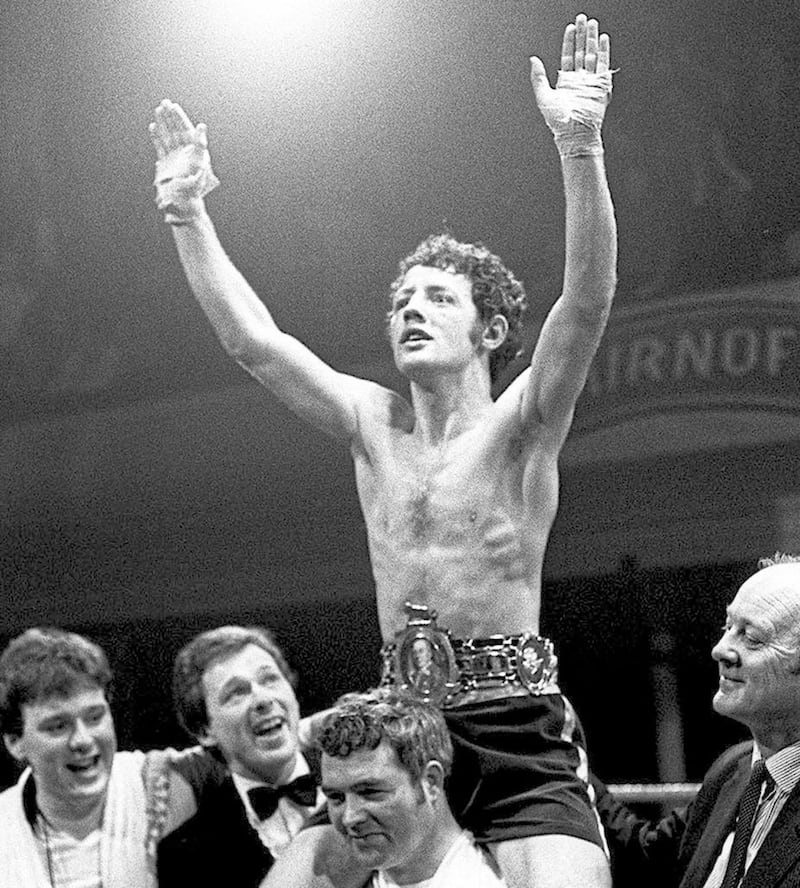

WE begin in London in June 1985. That night at QPR's Loftus Road stadium Barry McGuigan beat Eusebio Pedroza to win the featherweight championship of the world in a battle that has retained it's status as the biggest fight, and one of the greatest events, in Ireland's sporting history.

Barney Eastwood, promoter and manager, was helping McGuigan prepare for his date with destiny when news of another undercard drama broke.

‘BJ’ takes up the story: “Jim Jordan came running up to say: ‘Eddie Shaw (coach) wants you down right away’.

“I asked him what was wrong and he says: ‘Dave Boy (McAuley) has broken his left hand. He wants to be pulled out’.

“So I went down and I said to Dave: ‘Look, you could beat this boy (Bobby McDermott) with one hand, all you have to do is stand there and jab, jab, jab…

“He said it was too sore. I said: ‘Tell you what, if you don’t hold your own in the first round I’ll pull you out.”

McAuley nodded in agreement and a short while later he knocked McDermott out with his good hand.

In boxing, victories are building blocks and after a couple more wins Larne flyweight McAuley captured the British title and moved into pole position for a crack at Fidel Bassa’s WBA belt. But he lost twice to Bassa and his progress stalled as confidence and self-belief drained away. That could have been the end but BJ found a way to make McAuley believe in himself.

“He was working hard to try and improve and there were a lot of good people around him like Eddie, John Breen and Paul McCullough,” BJ explains.

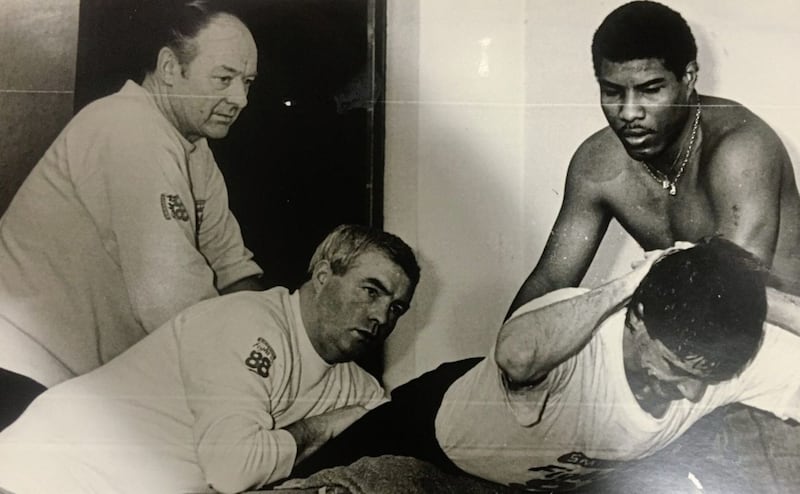

“Eddie was a guy, like John and the other trainers who would have told you: ‘I don’t know it all’ but he picked up a lot of things from fighters and trainers coming in. Bernardo Checa (a fighter from Panama who went on to train ‘Hands of Stone’ himself, Roberto Duran) was in town at the time and he came in to spar.

“I said to him: ‘McAuley has got loads of guts, there’s plenty of fight in him and he’s a lot better than you’re seeing’. I was sure there was something holding him back; he just couldn’t take that final step.

“I was always very friendly with Dave Boy. He didn’t give a damn about fighting anybody. He used to say: ‘What weight is he? What size is he? Aye, that’s ok, I’ll fight him!’ He was never one to turn down a battle and I could see something in him if we could get it out of him.

“Anyway, Hilario Zapata (former WBA flyweight champion) had got into some sort of trouble and he was out of boxing and had his licence suspended.

“Checa told me: ‘Zapata is doing nothing and he’s on the straight and narrow now’ and I said: ‘Would he come in for a spell’. He asked him and he came in and worked with McAuley for quite a few months.

“He knew all the tricks. He was a very skilful fighter, very cute… He could spot big faults, two or three serious faults in McAuley. McAuley liked him and they worked together and Zapata showed him so much in those few months and all of a sudden I could see that he had taken the step, he was a new man.

“Whatever had been holding him back, he just decided: ‘I’ll go for it’. It was marvellous the way he was able to do that and I’ve seen it in other fighters, I’ve seen it in footballers too.

“They’re working hard, they’re eating well but they just can’t make it. You need something different to pull it out of them.”

McAuley went on to beat Duke McKenzie to win the IBF flyweight title and then defended it five times in a series of thrillers. He was never, ever, in a bad fight.

By the time McAuley had become world champion, Eastwood and McGuigan had parted company. Their split, a falling out that ended the harmonious days of ‘Thank you very much Mr Eastwood’, ripped apart what had appeared to be an unbreakable father-son bond.

The Eastwood-McGuigan rise was a harmonious white knuckle ride but the fall, which came after McGuigan's loss to unheralded Steve Cruz in Las Vegas, shattered their relationship beyond repair.

“I spotted him (McGuigan) early on and I thought he had a lot of potential,” BJ recalls.

“If you let him take the centre of the ring and let him come forward he could destroy you.

“His one big fault was that anybody who could keep the centre of the ring and make him go round them caused him problems. He couldn’t go backwards, he had no reverse gear and he found it very hard with somebody who could straight jab him.

“We could never, ever teach him to move his head properly and slip punches and when he met guys with big jabs, left or right hands, he found it very difficult. But he made it anyway. People say he was well matched and that I matched him very well and I suppose I did do that because I was aware of his faults.

“But that doesn’t take away from him being a world champion and you’re not a bad fighter if you become world champion.”

McGuigan had already defended his title twice – against Bernard Taylor (at a packed Kings Hall) and Danilo Cabrera (at the RDS) - when he travelled to Vegas to meet Cruz and lost his belt.

Now over 30 years since the split, his former manager has come to terms with the acrimony: “These things happen,” BJ says.

But he recalls his forlorn efforts to do a deal with Wilfredo Gomez that could have made the Clones Cyclone Ireland’s first ever two-weight world champion. For him it was an opportunity missed.

Gomez had been a world titlist at super-bantam, featherweight and super-featherweight but the word was that he had lost his fire and that one more payday was all he was after.

“At the finish-up, he (McGuigan) had too many advisors and he stopped listening to me,” says BJ.

“He would listen to anybody only me probably.

“I went to Puerto Rico and signed up Gomez to fight him. He was the super-featherweight champion but he hadn’t fought for a year or more.

“The WBA were saying to him: ‘Look, we know you need a payday and then you’re stopping but you’ll have to make a move shortly or we’ll have to strip you (of the title)’.

“I stayed in San Juan (capital of Puerto Rico) for a fortnight and I met his manager. Gomez was a nice lad and a terrific fighter but by that stage he was nearly three stone over the weight.

“Anyway, his manager said to me: ‘There he is, he’s at the end of his career and he’s only looking for one thing: A good payday and he’s gone. I’m not saying he still can’t knock you out with one punch, but he’s at the end of the road’.

“So we talked terms and I signed an agreement for him to fight McGuigan and it was a big scalp.”

A clause in the contract stated that if McGuigan won the super-featherweight title he’d have had to give up his featherweight belt. But if he lost, he’d keep the featherweight title.

“It was commonly known in San Juan that Gomez was past his best,” BJ continued.

“Anyway, I came home delighted, I was paying a lot of money for him to come and everything was signed and sealed and the (British Boxing) board had agreed to it.

“So McGuigan was on a good one because if he did lose at 9st4lb, he still retained his featherweight title. I met him outside Enniskillen. I said: ‘I’ve something very important to tell you’ and I explained it all to him.

“He said: ‘Who?’ I said the fighter’s name and he said: ‘I’m not fighting him, he’s a three-time world champion’. I said: ‘Yes he is’ and I went into all the detail.

“I spent half-a-day trying to coax him but he wouldn’t fight him under any circumstances.

“I told him, this is an easy fight, it won’t go four rounds, the fella is only here for his final payday. It’s a big, big scalp and it would be wonderful for you. But he wouldn’t fight him. I pressed it home and pressed it home but it never happened.

“He was listening to everyone except me who was trying to do my best.”

Not long afterwards, McGuigan faced Cruz at Caesar’s Palace and a disastrous final round cost him his title. He parted company with Eastwood and didn’t box until almost two years’ later when he made a comeback under new management. He finally bowed out for good after losing to Jim McDonnell in 1989.

Most recently the Clones Cyclone remerged on the Irish fight scene and helped Carl Frampton achieve what had eluded him: world titles in two weight classes. Sadly, that working relationship has also broken down.

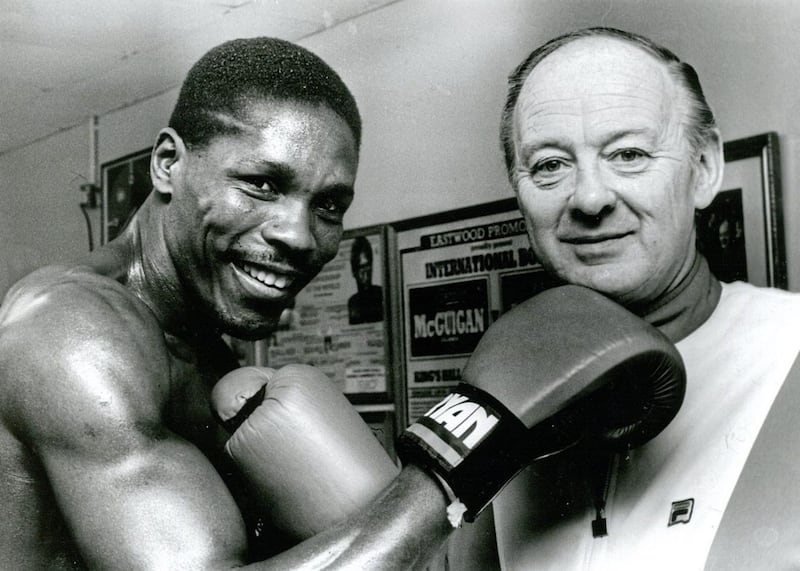

Not long after his split with McGuigan, Cookstown-born BJ came across the man he rates as the best fighter he ever worked with; Venezuelan welterweight Cristanto Espana. Nowadays many Irish boxers travel abroad to train but back then Eastwood’s pulling power enticed fighters from around the globe to come to Belfast and Espana couldn’t come quickly enough.

A tall, lithe southpaw, with built-in radar and concussive power in both hands, he was a class act who went on to win the WBC and WBA welterweight titles after a chance meeting in Venezuela.

BJ explains: “His brother Ernesto was lightweight world champion and I met him at a WBA meeting.

“He came over to me and said: ‘I’d love you to come round with me to the gym and watch a brother of mine’. He said: ‘If you like him, he’ll go home with you’.

“I asked him if he was any good and he said he’d let me make up my own mind. So I went to see him spar and he was only in half-gear, he was just playing with this guy he was sparring.

“His brother asked me what I thought and I said: ‘He’s very good’. He said: ‘I’ll tell you something and remember it: I was lightweight champion of the world, but I’m only a bum compared to Crisanto. He can fight’.

“At that stage he was 22 or 23 and you couldn’t have met a nicer fella. He was a big, tall guy and people thought that when they got in close to him they could hit him with bodyshots but he would have killed you when you got inside.

“He is a very kind guy, he would be sparring fellas for three or four rounds but after he got the better of them he did very little, he realised that they were out of their class and he didn’t punish them. I’d say he was the best I ever had.”

That is high praise because there were so many world level fighters in his gym including Belfast’s own Hugh Russell. A medallist at the Moscow Olympics, 'Wee Red' went on to win the British bantamweight title and he hung up his gloves after stopping Charlie Brown in his third defence of the flyweight belt.

“Hugh was a wonder,” says BJ.

“A great lad, I never had a bother with him. He got on with it and he was right up there, very close to a world title.”

Paul ‘Hoko’ Hodkinson was another. ‘Hoko’ – “a very good fighter and a worthy world champion,” according to BJ - relocated from Liverpool to join Eastwood’s Gym. The Scouse featherweight won British and European belts and then captured the WBC world title, successfully defending it against McGuigan’s nemesis Cruz.

In the build-up to his world title shot he met classy former Mexican contender Eduardo Montoya in Manchester and would have lost had it not been for another example of Eastwood’s ability to think clearly under pressure.

“His original opponent pulled out and Montoya came in,” BJ explains.

“He had been a good fighter but was a bit over the hill and he didn’t arrive until the night before the fight - at that time you were allowed to do that.

“He was 7lb overweight but his trainer says: ‘He’ll be nine stone in the morning’.

“I was thinking: ‘That’s a load of nonsense’ but he turned up on the scales nine stone exactly.

“When the fight started, Paul went straight at him and the boy slipped two or three shots. He put himself back in the corner, Hoko threw a punch and the Mexican hit him on the chin and down Hoko went.

“At the end of the round, we freshened Hoko up but he still wasn’t too good. He was saying: ‘Where am I? Who’s winning the fight?’

“I thought hard about pulling him out and I was 90 per cent sure I would. Then it struck me: Seven pounds off overnight? The other boy could hardly stand nevermind box.

“I thought, I’ll let Hoko out and if he hits this boy with one punch it’ll go our way. He went into the middle of the ring, caught him and the other boy was sprawled out, out for the count.”

All’s well that ends well.

Thirty-five years on from that unforgettable night at Loftus Road, BJ has a vast catalogue of stories to tell. He rose from humble beginnings in Cookstown to live successful parallel lives in sport and business and, although he hasn’t been in the best of health recently, he’s as sharp as ever at 88.

I'll bet he beats the count…