THAT familiar voice, always so confident and knowledgeable, wavers as Mike Costello talks about his late father.

Like so many thousands of other Irish men and women throughout the 1950s, Peter Costello, from the tiny coastal village of Spiddal in county Galway, swapped the west of Ireland for the chance to find prosperity in lands far away. Some of Peter’s brothers and sisters chose to cross the Atlantic to the USA, but he decided to try his luck in England.

And so he swapped the rugged beauty of Connemara for the unfamiliar streets of London and he took up a pick and a shovel and went to work. It was in London that he met Annie Burke, from Loughrea in his native county, and they married and raised their family in Camberwell, in the south-east of the city.

He passed on his pioneering spirit to Mike. His son started in the BBC accounts department as a 16 year-old but has risen through the ranks to become 5 Live’s popular and respected athletics and boxing correspondent. Sadly Peter didn’t live to hear Mike call the track action at the biggest sporting event in Britain’s history – the 2012 London Olympics.

On a magical ‘Super Saturday’ evening at the Olympic stadium in the East End, the Games reached an exhilarating crescendo. First long jumper Greg Rutherford won gold and when heptathlete Jessica Ennis did the same it sent the 80,000 delirious fans into a frenzy. Creating what Costello described in his commentary as “a wave of emotion” they cheered on Mo Farah in the 10,000 metres final and he completed a stunning hat-trick – three gold medals for Britain in the space of 44 breathless minutes.

Millions around the world listened to the radio coverage as the 25-lap race reached a thrilling climax.

“He is being carried on this wave of emotion… Farah hits the front… and Farah wins gold!” went Mike’s unforgettable commentary as Farah crossed the line.

A recording of Costello’s spine-tingling and passionate description of the events of ‘Super Saturday’ has since been enshrined in the BBC archive and it will remain there forever as a lasting legacy to his commentary skill.

More than that, it meant that Mike had kept the promise he made to his father.

“My dad died in 2009,” he explains, the emotion clear in his voice.

“He was so proud of our family and I remember thinking: ‘I’ll get our name in the BBC archives dad, I’ll get it there for you’.

“Whenever anybody goes back to play the BBC radio commentary of that night, they’ll see the name Costello in there and that means a lot. It was really important to me because my dad was so proud of our name and the family and the roots and everything so to have it lodged in there is really special.”

Mike, who turned 60 earlier this month, is a Londoner at heart but Irish blood flows through the veins of the former amateur boxer and coach who, having commentated on close to 100 world title fights, is at least as synonymous with the noble art as he is for his work in athletics.

“We grew up in the Irish diaspora in Camberwell,” he explains.

“There were tons of Irish families around and in both schools I went to it was a third Irish, a third West Indian and a third English.

“As a kid we were either labelled ‘thick Micks’ or ‘Irish bombers’ because it was at a time when there was a lot of bombing in London but we just seemed to ride the tackles. Anyway we were hanging around with a lot of West Indian kids who really were getting stick that we just couldn’t understand.

“It was a time that you really felt the need to be around that wider Irish family because you had a sense that we were all sticking together. We were going to Irish dances and festivals and that sense of Irishness was a big part of our youth.”

Both of his parents were raised on farms, which are still going, and both came from big families. Mike has visited Loughrea and Spiddal regularly throughout his life and also has aunts, uncles and “tons of cousins” from Boston to New York.

“I’ve got as much family in Boston as I’ve got in London,” he explains.

“Any time there’s a fight on the eastern seaboard I try and get to see the clan over there.”

As a youngster the family would sometimes catch the number 36 bus and travel the couple of miles to The Harp Irish Club where his parents would enjoy meeting old friends, hearing the news from home and enjoying the ceili music. On other occasions, the jigs and reels would even come to the Costello household.

“We were a long, long way from well-off but what we didn’t realise at the time is that we had a lot of what sociologists would call ‘social wealth’ we had a very happy family life,” says Mike.

“When you’re a kid all you want is money to spend and there wasn’t a lot of that but we had a very, very good upbringing in terms of friendly faces, laughs and happiness.

“They were great days but there was definitely a period when I wanted to leave all that behind and when I look back now, I was just a kid wanting to make his own identity because it was a great time.”

Like many a teenager he had a rebellious streak and, also like many a teenager, he saw his future as working in television. So after finishing his ‘O’ Levels in 1976 he wrote to the BBC and some other broadcasters asking for a job: ‘Dear sir/madam, My name is Michael Costello…’

It couldn’t happen nowadays but it paid off and he’s been in the BBC ever since.

“I genuinely don’t know why I did that,” he says, 44 years on.

“Just as I was about to go back to school for the sixth form the BBC replied and said they had a vacancy in the accounts department and would I come for an interview.

“I got the job and started in accounts. I had zero qualifications in terms of anything that mattered for broadcasting or any university degree but it was a different time.

“Certainly for someone from a working class background like me, it was very unusual to go to university but it wasn’t unusual to be going out to work at 16. My own son can’t believe it was like that then but it was the norm.”

He says he “made a nuisance of myself around the sports room” and it was his sheer enthusiasm that got him noticed and convinced a producer at the BBC World Service to give him an (unpaid) role on Saturday’s as a ‘runner’. In those pre-internet days that meant he took results from the chattering tele-printer and literally ran then to the sports desk where they were read out on air.

Eventually an opportunity came up as a broadcast assistant. Mike was encouraged to apply, did so and got the job to move onto the sporting ladder he wanted to climb.

“It was tiny steps up the ladder but one-by-one they got me higher and higher,” he says and it was his involvement with boxing that enabled him to eventually make the great leap forward.

Boxing began for him at Lynn AC at first in the ring and then as a coach.

“Everything me and my brother did was basically part of a herd instinct in south-east London,” says Mike.

“We weren’t pushed towards the gym by dad or our uncles or anyone else. In south-east London in the 1970s there just were so many boxing clubs and every kid, even if he only went for one night, went at some stage in his life.

“I just happened to like it more than others. My brother had a couple of bouts and he won one and lost one and walked away but I stuck around for a long time. I had about 65 amateur bouts over about nine or 10 years and then I coached for about the same amount of time.”

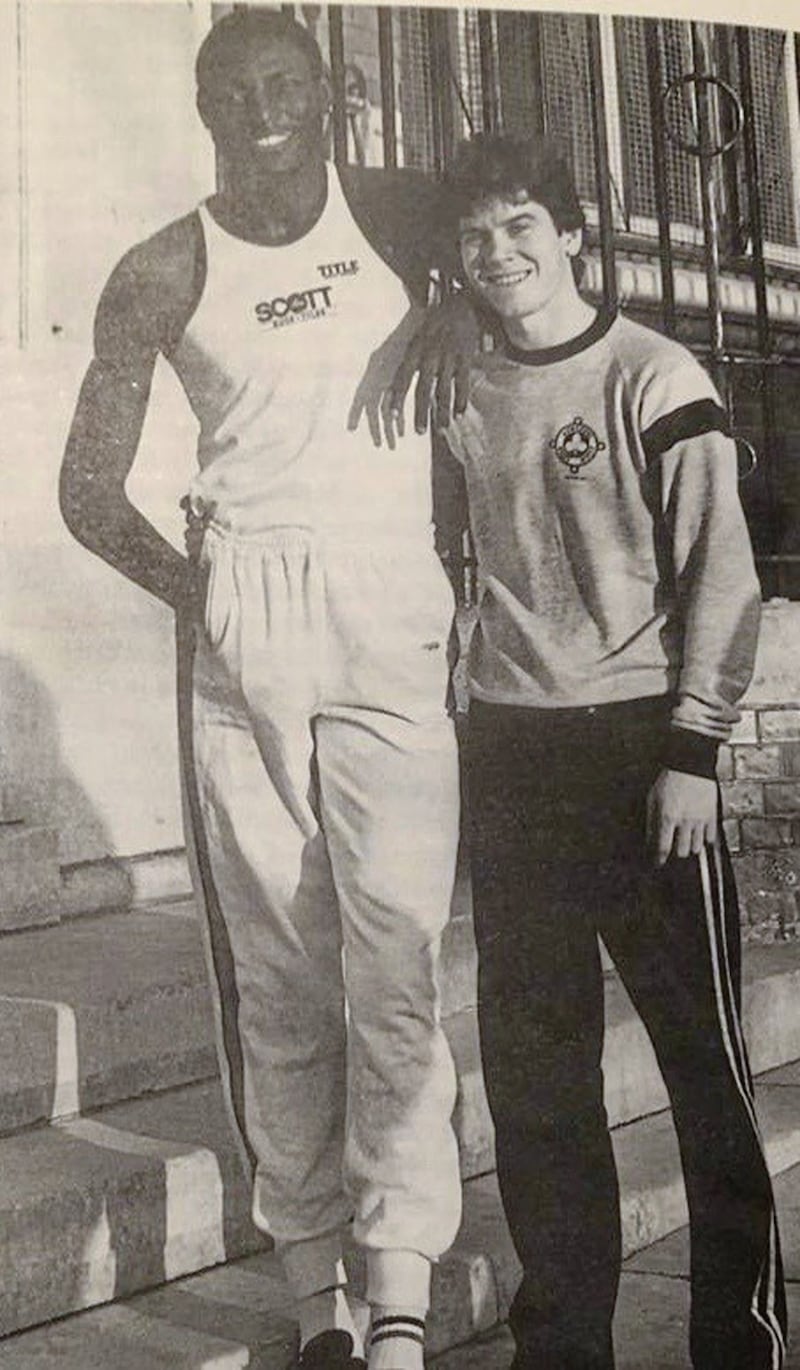

After he hung up his gloves he trained London lads to national championships and heavyweight Henry Akinwande (who went on to fight Lennox Lewis as a professional) to qualification for the Olympic Games in 1988. But his career was increasingly soaking up his time and after a period trying to fit “nine days into a week” and he had make a decision.

“I was starting to slowly climb the ladder at the BBC so it got to the stage where I could spend less and less time at the club,” he recalls.

“It got really difficult because you build a bond with the boys but then one night you have to say: ‘I’m sorry lads, I won’t be here tomorrow night, I’m working’. It just seems like an excuse. I had been during four or five nights-a-week and a Sunday morning and I went down to doing two or three nights and then I ducked out of it and it was horrible.

“It was like letting go of a family but I had to do it because I was working for the World Service at the time and their sports coverage moved form 18 hours a day to 24. It only sounds like six hours but the job suddenly started to incorporate night shifts which had a massive effect on the rota and meant there was virtually no time when I could promise to be at the gym. So that was when the BBC took over really and I was dragged away from the boxing club.”

He had hoped to forge a career in boxing but the World Service budget didn’t stretch to buying commentary rights so he gave up on it. But he was still making progress and was sent for voice lessons before his first commentary stint came at the World Athletics Championships in 1995.

“They weren’t raving about my efforts at the BBC but they did say they’d give me another go and over the years it increased,” he says.

His first commentary at the Olympics was in 2000 at Sydney and two years later another opportunity knocked – the one he had been hoping for - and he was ready, able and willing to open the door.

“The luckiest strike of my career was in 2002 and it’s why I’m doing boxing now,” he explains.

“The 5 Live commentator at the time was John Rawling (now the boxing commentator on BT Sport).

“After three days of the Commonwealth Games in Manchester he lost his voice and they didn’t quite realise how bad it was until they got him to do a preview at half-five on the Monday evening.

“The competition started at six o’clock and he couldn’t utter a word so the producer came running up, ashen-faced and said to me: ‘Mike, Mike, Mike, we’re desperate, can you please get us through tonight?’

“I did the commentary and they liked it, John didn’t get his voice back to I did the rest of the Games and that established me within 5 Live.

“After that I was always in their thinking and then in 2005 John went to ITV who had decided to get into boxing based around Joe Calzaghe and Amir Khan. They head-hunted John and he went there and I got the job at 5 Live as the boxing and athletics commentator. That’s the story really and I’ve been there since 2005 and it has just been the greatest time.

“My tenure in boxing has coincided with Floyd Mayweather and in athletics with Usain Bolt and that’s not to mention all the British stuff which has been fantastic – Carl Froch, Tyson Fury, Anthony Joshua, Mo Farah, Dina Asher-Smith, Jessica Ennis-Hill… I have been bloody lucky because it has been a joy.”

Peter Costello must be very proud.