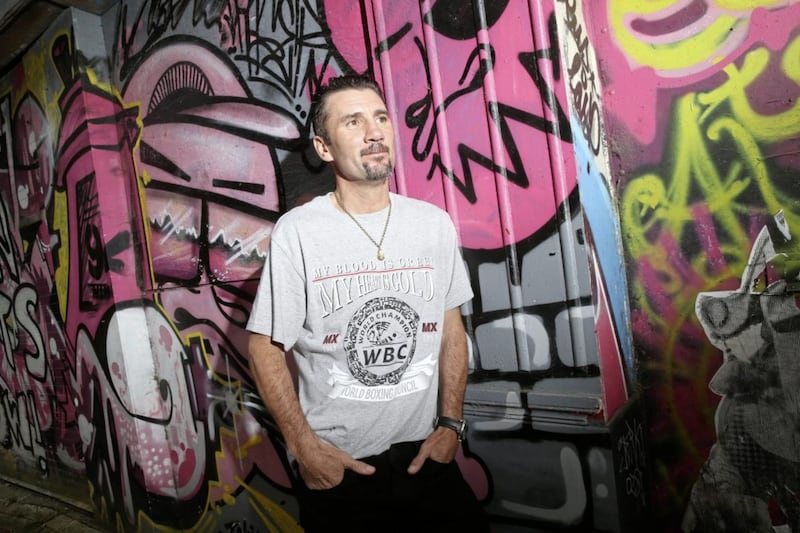

“I DUNNO… it’s just weird. Things are weird.” Wayne McCullough’s voice fades to nothing as he attempts to make sense of pandemic life in the Las Vegas suburbs. For the past two months, every day has followed pretty much the same routine.

Get up, go for a run, home for a workout, chill out for a few hours, do another workout, then a couple of scheduled Zoom sessions with clients, a bit of TV, dinner, then bed.

As we speak, an old friend drops off a food parcel for the family. Like McCullough, Frank Fusco left Belfast many moons ago, but his generosity of spirit all these years on serves as a regular reminder of home.

“We told him we’re fine, but you know the old school. We’re the ones who should be getting things for him…”

That unexpected visit was the only thing to distinguish this day from the last, or the next. McCullough sniggers at the repetition of the daily grind but, for a man who spent the guts of three decades living to rule, this is nothing out of the ordinary.

In some ways it is reminiscent of the monk-like discipline and attention to detail he would bring to training camps when shooting for the stars as an amateur, then in the paid ranks. It has also afforded time for reflection.

This summer marks 25 years since McCullough journeyed into the unknown and returned with the green WBC belt he had craved since seeing the heavyweight version draped over Muhammad Ali’s shoulder.

With an unbeaten 16-fight record, all of the bantamweight world champions were on the radar by that stage. Yasuei Yakushiji represented, by some distance, the toughest assignment. Alongside Germany, Japan wasn’t somewhere you went and won in the mid-1990s – especially not against the country’s golden boy.

Agreeing to take on a fight like that instantly placed McCullough in knockout-for-a-draw territory, but impatience was eating at him. The ‘Pocket Rocket’ wasn’t in the mood for hanging about any longer than he needed to.

“When I turned pro, I wanted to be world champion within two or three years,

“I fought 11 times in the first year. After each fight I took two days off because I couldn’t move, otherwise I’d have been straight back into the gym.

“I fought Victor Rabanales in June ’94 and in September that year I could and should have fought for the belt but Yakushiji wanted a couple more defences in between. They paid step-aside money - I got $50,000, but it should’ve been a lot more.

“My management wanted me to sit and wait for the Yakushiji fight, but I couldn’t do that. I’d been active up until then, so why slow down now?

“I took a fight in Dublin against Fabrice Benichou, moved up to super-bantam for that. He was still a live guy. It was a risk, but I didn’t want to fight dead bodies or guys who were done.”

Including Benichou, McCullough ended up having three fights between Rabanales and Yakushiji. When his shot was eventually guaranteed, veteran trainer Eddie Futch staggered the training camp from Vegas, to Utah, to the sunshine paradise of Hawaii.

A week before the fight, they flew to Nagoya, the words mission impossible fuelling the McCullough fire.

***************

THE fighter and his team weren’t the only ones with a vested interest heading to Japan. Documentary makers Dermot Lavery and Michael Hewitt had followed the Shankill Road man from the first bell of his pro career across the Atlantic, though the seeds of their association were sown much closer to home.

“We made a small film in 1992 going into ’93 called Belfast Boxers, featuring Wayne, Dave ‘Boy’ McAuley and Joe Lowe,” explained Lavery.

“That’s when we picked up Wayne’s story, and when we finished that we realised his story was really only beginning. He’d won silver at the Olympics in Barcelona, and here he was setting off for a new world and a big adventure.

“The thing about Wayne from the very start was his authenticity – from the day we met him to the day he won his world title and beyond, he has never changed how he faces the world.

“There’s something lovable about that.”

The BBC liked the DoubleBand Films pitch for a follow-up, thus Down the street of Dreams was born. The idea was to follow their subject all the way to world title glory. Despite McCullough’s stellar amateur career, that was far from guaranteed.

Yet after over two years of access-all-areas material charting his rise, the moment of truth would come in the Far East.

“When you saw him, this wee man from Highfield estate, setting off to the other end of the world with this small entourage, not a huge support, the courage and the character of that… it’s just immense,” said Lavery.

“I remember being struck by that at the time, and I still am today.”

Staying in the Nagoya Hilton Hotel, McCullough was looked after by a welcoming Japanese public but never lost the sense of being behind enemy lines – especially in the days leading up to the fight.

“Two nights in-a-row Yakushiji’s people kicked my hotel door at about two o’clock in the morning. The first night I got up and looked through the peep hole, the second night I didn’t even get out of bed.

“We always switched our meals as well – whatever I wanted, somebody else would order it. You couldn’t take any chances.”

Undefeated in his previous 23 fights, all but three of which had taken place in Nagoya, Yakushiji was the king in his adopted home town. Determined to squeeze every last drop out of that advantage, the mind games carried into the weigh-in.

“He came in wearing a pair of Bermuda shorts, I got on the scales and weighed 8st 5¾ - just under the weight. He jumps on and is four pounds over, then he yells out ‘oh no’. That’s the only thing I heard him say in English the whole time.

“He went away and came back 20 minutes later – he didn’t even go and sweat, it was all a big con. He comes back in wearing a pair of Speedos, jumps on and he’s under weight. By the time he got back on the scales I was probably eight stone nine!

“He was trying to get under my skin but I’d been around the world as an amateur, seen different cultures, different fighters… I’d seen everything. You weren’t going to pull a fast one on me.”

And with Futch and Thell Torrence in the corner, McCullough never doubted his ability to upset the odds, no matter how strongly they were stacked against him.

“Eddie was like the internet before the internet was even a thing; what was in his head was gold.

“By then, he had seen everything. I can’t even describe the stuff that came out of his mouth, the stuff he taught me; it’s priceless. And because of that, because I had him there, I felt unbeatable; I felt like Superman.”

The fight itself took place at 2pm on the Sunday afternoon, inside a packed Aichi Prefectural Gym. Fight day rather than fight night - another sign of being a stranger in a strange land.

A smattering of Irish fans made their presence felt as McCullough walked to the ring but there were probably no more than 20 in total, between family and friends who had made the trip and a handful of ex-pats there to lend their support.

“And the chef from the hotel,” smiles McCullough, “the next day he sent me up a bottle of Guinness in an ice bucket.”

Staring through a camera lens, Lavery recalls an almost eerie feel as the world title bout was about to get under way.

“It just didn’t feel like a boxing world, or a boxing crowd,” he said, “it was the strangest thing.”

“Quiet,” agrees McCullough, “in a way where it was nearly sort of spooky.”

Inside the opening 10 seconds, however, the serenity of his surroundings were rocked and his senses shaken when a chopping right hand from the taller Yakushiji landed flush.

“He came out all guns blazing. You look at that right hand in slow motion, it was bang on the chin - it would’ve knocked most people down.

“Eddie told me he was going to start fast; everything he said would happen over the course of that fight did. We knew he would start strong and finish strong.”

The Belfast man’s backside didn’t touch the canvas once in a 34-fight career that featured clashes with bangers like Naseem Hamed and Erik Morales, and McCullough’s legendary granite chin saw him weather the early storm before finding his own rhythm.

By round two he was closing the gap to Yakushiji, landing double jabs and uppercuts to head and body, the relentlessness of his work putting McCullough in total control by the midway point.

“Yakushiji had a great straight jab, so Eddie had me working on the jab the head, jab to the body, slip his right hand, come over with the jab. We did this all in camp but he didn’t tell me until the day itself in the dressing room, ‘I want you to go out and out-jab this guy’.

“I’m thinking ‘what?!’ But everything came so natural because we had done so much work on it. Boxing is all automatic, all reflex motion, so he was coming straight down the middle and I was coming off the sides, the body shots were killing him.

“He groaned one time early on and I remember thinking ‘it’s not going to be this easy’.”

As Futch predicted, Yakushiji rallied late on, the crowd finally responding in his hour of need.

“I was well ahead by the 10th round, and from then on I’ve never felt an atmosphere like it against me. It actually gave me shivers down my spine – it was really deafening loud.

“Eddie just told me to box, move around, don’t do anything crazy; I just had to keep my head. He came on strong but I knew I just had to see it out. I had the fight in the bag.”

McCullough fell to his knees when the final bell brought a thrilling contest to its climax. Despite the one-sided nature of the fight, though, the outcome remained far from certain, with McCullough’s destiny now in the hands of the judges.

When a split decision was returned, he feared the worst.

“My heart sank; I was thinking ‘here we go’. I’d done the work, done everything perfectly.

“Then they called my name after the last scorecard, and your life changes forever... it was the best moment of my pro career.

“The WBC belt, from I was about 15, I wanted that belt. And now I had it.”

His small band of supporters poured forward and chanted ‘Wayne’s World, Wayne’s World’ from the ring apron, watching on as that famous green strap was wrapped around his waist.

The party was already well under way by the time he got back to the hotel. Dermot Lavery and Michael Hewitt arrived with the champ.

For them too, it was the perfect end to the perfect story.

“We were just taking it as we went; we wanted to follow him to a point where we felt it would complete the arc – had he not won in Japan, I think we would’ve continued on until he had won a world title.

“Setting off to America then, his visibility here was lower, it gets harder to sustain yourself over years. It was only really when he became world champion that he probably felt that love again.

“It was an inspirational end really, and one he deserved.”

**************

THE end of a chapter for McCullough, but the end of the road for Yakushiji. Just eight days before stepping between the ropes on July 30, 1995, the defending champion had turned 27.

The McCullough defeat was the first he had suffered since coming out the wrong side of a six round split in just his fourth fight seven years earlier – yet it was the last time he was ever seen in a boxing ring.

Nowadays, Yakushiji is an occasional film star and commentator, around commitments at the Nagoya gym he opened in 2007. Attempts to speak to him for this article met with silence.

Managerial issues have been cited for his early retirement, while the failure to strike a deal with an old foe has also been mentioned in despatches.

“To understand Yakushiji,” said Toshihiro Yamanaka of the Asia Boxing Commission, “you need to know Tatsuyoshi.”

Joichiro Tatsuyoshi was named after Joe Yabuki, the main character of the boxing anime ‘Tomorrow’s Joe’. He was a well-loved figure in Japan in the early ’90s, and cemented that popularity when he defeated former McCullough foe Victor Rabanales to claim the vacant WBC title.

His second defence was a huge all-Japanese showdown with Yakushiji.

“Yakushiji was unknown until he fought Tatsuyoshi,” adds Yamanaka.

The fight generated massive attention, and massive money, Yakushiji taking a majority decision.

For years, both before and after his loss to McCullough, speculation swirled around about a potentially lucrative rematch between the two, but it never came to pass, and Yakushiji sailed off into the sunset.

“I’d have gone back to Japan and fought a rematch no problem; he deserved a rematch, but it was never even mentioned. It’s weird,” says McCullough.

“I’ve had no contact with him at all since then… my brother-in-law was in Japan about 10 years ago funnily enough, he stayed in the Nagoya Hilton too and when he walked out the front door he noticed a Ferrari sitting there with the words ‘Yasuei Yakushiji: WBC champion’ on it.

“Apparently he parks his car there a couple of times a week, goes out on the town… that’s awesome.”

From one hometown hero to another.

When Down the street of Dreams eventually aired, it climaxed not in Japan, but with McCullough walking out into the dazzling white lights of a packed Kings Hall. The Belfast boy back in town, feeling the love.

Twenty-five years on, that victory in Nagoya still stands on its own as the best achieved by any Irish boxer overseas. Big nights and big fights would follow, but nothing would ever surpass the day when Wayne stood on top of the world.