FOR the last 14 years, John Lowey has been back where it all began. Well, almost. Dad John and mum Peggy still live at Durness Walk, the family home for 55 years and counting, their eldest son’s flat just a short dander through the familiar streets of Ballybeen estate.

Living by himself, with his four children all up, Lowey operates at his own pace. These days he works as a taxi driver, the freedom and flexibility of the job suiting a life that remains open to possibility.

“My friends call me ‘yes John’,” he smiles, “any time they phone me and say, do you want to go here, do you want to go there… we’re heading to Finland, are you up for it? Yes, no problem, let’s go.”

In mid-November 1997, John Lowey was a long way from east Belfast when the phone rang. Chicago had become a home from home since a failed brain scan brought a promising pro career to a shuddering halt, forcing him to relocate Stateside in a bid to salvage something after three lost years.

On the other end of the line was Mike Joyce, the Chicago-based promoter charged with steering his career back on track. Married to Muhammad Ali’s daughter Jamillah, Joyce’s link with the sport’s ultimate deity gave him plenty of pull, but edging Lowey into the world title mix was proving anything but easy.

The reason was simple; he was too good - certainly too good to take a chance against, the risk-reward scales tipping too heavily towards the former. As Steve Bunce might say, he was chairman and secretary of the ‘who needs him?’ club.

“John, I’ve got some big news. A world title shot has come up… it’s quite short notice.”

“How short?”

“Three weeks…”

“Against who?”

“Erik Morales… in Tijuana. The guy he was supposed to be fighting has picked up an injury and is out of the show.”

Morales was the new darling of a thriving Mexican boxing scene, and had hammered his way to an unbeaten 28-0 record, 21 by knockout.

At 21 he was 10 years Lowey’s junior, and in the decade-plus that followed Morales would establish himself among the very best of a stacked generation, the trilogy fights with Marco Antonio Barrera and Manny Pacquiao cementing a remarkable legacy.

The fight with Lowey would be the first defence of the WBC super-bantamweight title he had ripped from the grasp of Wayne McCullough-conqueror Daniel Zaragoza in El Paso three months earlier, a much-anticipated Tijuana homecoming for this son of the city’s dangerous northside.

“December 12th... what do you reckon John?”

“Yes, no problem, let’s go.”

******************

THERE was no family history when it came to the noble art – not in name anyway. John Lowey’s father and uncles had spent their working lives under the shadow of Samson and Goliath, solid men hewn of shipyard steel but not a scrapper among them.

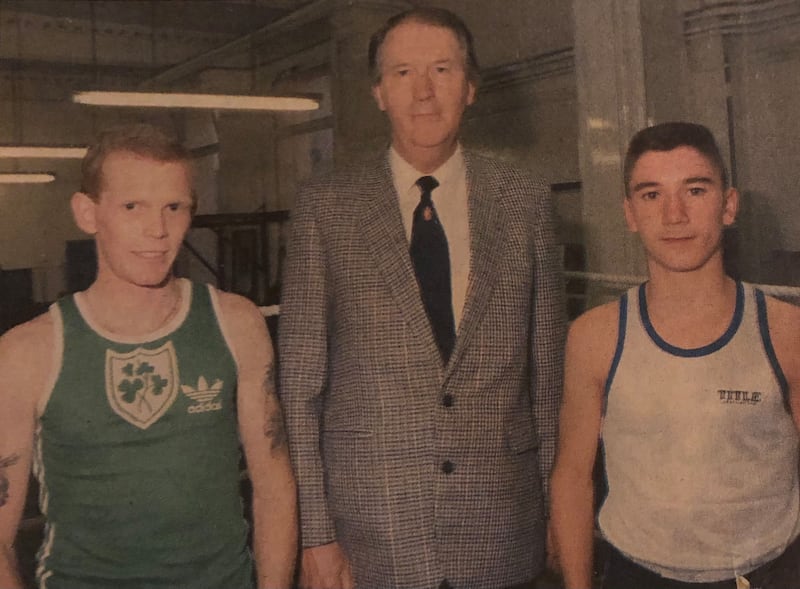

And it wasn’t until his early days training under the watchful eye of Herbie Young at Ledley Hall that Lowey found out about a blood link that went some way to explaining his own ease between the ropes.

“My granda on my father’s side used to box on the back streets. Apparently he didn’t want to taint the family name so he went by the name Kid Thomas.

“This had been going on for a while, he was doing well, then one of the neighbours said to his mother ‘there’s a boxing show on, do you want to go and see it? A young fella from the area called Kid Thomas is boxing’.

“So his mother went over but when she got there he saw her and threw his boxing stuff over the yard wall – that was the end of him. She didn’t want him to box and he didn’t want to let her down.”

Like his great-grandmother, Peggy Lowey could never bring herself to watch John in action either. Her support was constant, however, and if there were tickets to be sold at shows, she’d busily make her way around the hall. The second the bell sounded though, Peggy was nowhere to be seen.

Yet it was his mother who had, albeit inadvertently, played a key part in John Lowey taking up boxing at nine.

“She used to childmind for a fella Sammy Nicholson in Ballybeen, his sons Paul and Bill both boxed for Ledley Hall. I used to get a lift down with them but then there was some fall-out and I started getting the bus up and down the Newtownards Road myself.

“I was never a confrontational kid or anything, I wasn’t getting into bother, I just loved the sport, and the art of boxing.

“My first contest was in the local community centre, September 1976. That trophy is still in my mum and dad’s house. It’s funny now looking through old scrapbooks, they bring back memories of the early mornings, dad shouting up ‘right John, time for your run’ before he went to work.

“We’d have gone round to the track at Dundonald girls’ school and done sprints, him stood with the stop watch. My parents instilled that work ethic in me.

“A lot of my friends would’ve come to the club too at the start but they didn’t stay – they were coming to 15, 16, 17 years of age, wine, women and song, but I was focused.

“I knew what I wanted to do and where I wanted to get to. I wanted to go to the Olympics, and I wanted to be world champion.”

Lowey left school at 15 and started working at crockery company Hotelware, but boxing was all that mattered. He would do his roadwork at the crack of dawn before heading straight down to the club once his shift had ended.

It was during these formative years that the skills which would help him achieve both those heady goals were honed.

“Herbie always told us he couldn’t teach us everything, so he encouraged you to try and go around to different clubs and pick up as much as you could. We went everywhere.

“In 1986 I was over in London with friends and went to the gym Terry Lawless and Frank Bruno were in. I’d have done the pads with anybody and before I went back home he tried to get me [to turn over] but I said no.

“I was 20 then, and there was nothing in my head but the Olympics.”

To make it to the Seoul Games in ’88, Lowey would have to get the better of his personal bête noir - bantamweight rival Roy Nash.

The Derry southpaw held a 5-1 winning record when the pair were ordered to box-off but, before a packed house at Donaghmede leisure centre in Dublin, Lowey did the business to secure his spot on the Irish team.

Teenage team-mate Wayne McCullough, born and bred on the Shankill Road, famously carried the tricolour at the opening ceremony. Regardless of the tensions back home at the time, McCullough insisted it was an honour to be asked.

And, for Lowey too, wearing the green vest was never an issue.

“It wasn’t mentioned, not once. We were associated to Ireland and that was it.

“Making it to the Olympics was the pinnacle for me. I’d never really wanted to go pro or anything. I won two fights out in Seoul but lost the third [to Mongolia’s Nyamaagiin Altankhuyag] for a place in the quarter-final.

“I’d injured my knuckle before that but I was still gutted. Same as when I’d lost to the defending champions at the World and European Championships… for me, I never had that inferiority complex some boxers have.

“Anybody I ever fought at my weight, including Morales, I always – always - thought I could beat them.”

Barney Eastwood shared that belief and snapped Lowey up the second he landed back in Belfast.

After making his debut in December ’88, Lowey was unbeaten in 13 fights when the rug was whipped out from under his feet in 1991.

“I was to box for the IBO international title in Scotland when brain scans came back and showed what they called a cave of septum – basically a pin prick in the layer of skin that covers your brain.

“They said it had been caused by boxing… not by the time I fell off the garage roof twice in the one day, or all the times I fell out of trees when I was a kid. They told me it hadn’t been present in the scan I had done in Dublin before the Olympics three years earlier, so that was that...”

He was 25, and seemingly at the peak of his powers. And yet, with the horror of the near-fatal injuries sustained by Michael Watson against Chris Eubank months earlier still reverberating throughout the sport, Lowey was in no doubt.

“I was on the Gerry Kelly show saying my boxing career was over. With a wife and two young kids, I couldn’t take the risk. I was finished… but then I was asked to go to America.”

Mike Joyce offered him an unexpected second chance as he aimed to expand his Windy City stable. Lowey underwent rigorous testing in America and, this time, the MRI scans came back all clear. After three years away from the ring, he was good to go.

Seven wins in less than a year earned him a shot at the vacant IBO super-bantamweight title in the spring of 1995 – Lowey grabbed his opportunity with both hands, stopping Juan Camero in the fifth round.

It’s only in recent months he has got around to having the belt engraved with his name and that of his vanquished opponent.

“This is my mum and dad’s pride and joy,” he says, removing the belt from its box, “it’s no good to anybody else – you’d probably only get £500 or £1,000 if you went to sell it - but it’s priceless to me.”

Now the aim was to land one of the straps that would bring in the big bucks, but a challenge for Kennedy McKinney’s WBU title fell flat when Lowey was stopped in the eighth round – a first career defeat that left him facing a long road back to the top.

Earning what he could while dividing his life between Ireland and the States, at times it felt as though he was treading water. Away from family for long periods, thoughts of quitting – for good this time - regularly entered his head.

As 1997 drew towards a close, he had no idea where his career was headed, if it was headed anywhere at all. And then the phone rang.

******************

'Drug war massacre at El Sauzal’

‘Tijuana lawyer's son slain’

‘Resort seized by Mexican drug agents’

THE headlines from the time tell you all you need to know about the world John Lowey was about to step into.

In 1997, there were 318 murders in Tijuana as human trafficking and drug trades run by competing criminal gangs took a bloody toll on a city dubbed the world’s most dangerous.

For Lowey, though, the only threat would come from within the four walls of the Auditorio Municipal. A famed spot for lovers of the lucha libre wrestling scene, there was nothing staged any time a fresh-faced Erik Morales came to town.

“He had beaten Zaragoza, this was his big night back at home. I had three weeks’ notice… they thought I was cannon-fodder.”

They thought wrong. Anticipation levels soared following the chief support, a hostile home crowd baying for blood. But they weren’t going to intimidate the Belfast boy.

“Officials kept coming in, saying ‘TV wants you out, let’s go’. But I knew what was happening. You see away fighters being left in the ring for five or 10 minutes with the whole crowd around them, just you and them.

“I wasn’t going to let that happen – I kept saying ‘let them wait’, and eventually he had to come out right after me.”

Smoke billowed and mariachi music filled the air but Lowey’s head rocked back with laughter as the crowd booed his name - and he further endeared himself to the home support in the opening seconds.

Having noticed that Morales always whispered a prayer in the corner before the first bell, Lowey immediately raced across the ring and landed a left hook as ‘El Terrible’ turned around.

“To do that in Mexico… oh my God,” laughs veteran trainer John Breen, “when he came back to the corner I was saying ‘what the f**k are you doing?’ But John didn’t care.

“I had told John to go out, use your movement, don’t be having a war with this guy… John went out and had the war with him. But I think Morales was more intimidated that night than John was.”

Those opening moments set the tone for the rest of his challenge.

US boxing pundit Al Bernstein had Lowey winning the first two rounds until a clash of heads in the third left blood streaming from Morales’s left eye. Even though it was accidental, Lowey had a point deducted – and the same thing happened twice more in the fifth as the fight turned ugly.

Knowing the tide was going against him, Lowey kept coming forward, the sixth ending with a phonebox finish in the corner. However, having broken his right hand in the fifth, his challenge ended when the was unable to come out for the eighth.

“I was so proud of him that night,” says Breen, “John was one of the best to come out of Eastwood’s, a very, very special boxer. But, because of what happened, we probably didn’t really get to see the best of him.

“I didn’t realise how good John really was until then.”

“It was a chance to be in a big fight on TV,” adds Lowey, “but because I made it such a contest, nobody wanted me. It didn’t do me any favours boxing him the way I did.

“If I’d stayed in there and he’d knocked me out in the ninth or 10th round, it might’ve been different but because I retired on my stool, after giving him such a hard night, I was avoided.”

The next four years brought only four more fights, pushing two-weight world champion Oscar Larios all the way in 2001 before, at the age of 35, Lowey hung up the gloves. Johnny Tapia in New Mexico was offered but, by then, the fire had burned out.

“I could have got another few quid but I knew I couldn’t keep on going forever. Money’s not everything, not to me. I live on the fifth floor and every day I come down the stairs and go outside, I think ‘right, what’s today going to bring?’

“If my life’s a book, then boxing was only one chapter. As I say to everybody who gets into my taxi, what I’ve done with my life, I’ve enjoyed. What’s next? I don’t know, but I’m looking forward to it.

“I’m in a position where I can work when I want, do what hours I want and if I don’t fancy working today or something else comes up, I’ll go with that.

“I’ve a roof over my head, I’ve food in the cupboard… that’s all I need.”