THERE’S a certain kind of glow that radiates from elite athletes in their prime. Brendan Irvine, just a boy in Rio five years ago, now a man and Ireland’s captain when the actions begins in Tokyo next weekend.

Kurt Walker, carrying cooing baby daughter Layla, exudes contentment - time served in the shadows, now ready to seize his moment.

Up front are the Walsh siblings, Aidan and Michaela. Flanked by proud parents Damien and Martine, they are a picture of good health having just come up the road from their caravan retreat in Carnlough.

Once there, boxing takes a back seat. Anywhere else and it is all they think about, their history-making appearances now just days away.

The County Antrim Boxing Board have called Ulster’s four Olympians together for a reception at Belfast’s Balmoral Hotel on this bright Saturday afternoon in mid-June, a token of appreciation not just for the boxers but also for the coaches, clubs and families who helped shape them.

Paddy Barnes sr - whose son competed with distinction at the last three Games in Beijing, London and Rio – leads the well wishes, followed by Ulster Council president Kevin Duffy and Dominic O’Rourke of the Irish Athletic Boxing Association.

Reluctant to take any of the spotlight from the fighters, Irish coach John Conlan speaks briefly before Alex Maskey is invited to offer a few words ahead of the Irish team’s imminent departure for the Far East.

A talented boxer with Holy Family in his pomp, the MLA for west Belfast and former Assembly speaker lost only four of 75 amateur fights and remains a student of the noble art to this day.

He was just 12 the last time Ireland travelled to an Olympic Games in Tokyo. That was back in 1964, and it is a legacy already secured that Maskey so eloquently describes to the four 20-somethings eagerly craning their necks towards the back of the room.

“What you have done, and the scale of it, you might not realise until you’re much older,” he said, “but even today, people still remember and still talk about Jim McCourt, Seanie McCafferty, Paddy Fitzsimons... that’s something special.

“It’s an elite club to become a part of and, just as we are still proud of those men all these years on, every one of us here today is proud of you and always will be proud of you.”

Walking towards the hotel reception minutes later, those words are still ringing in Aidan Walsh’s ears.

“It’s amazing to think of that,” said the 24-year-old, a counter-punching master cut straight from the Jim McCourt cloth.

Six days on and Sean McCafferty and Paddy Fitzsimons are sat across a table upstairs in Castle Court. Both are in their seventies now but for the most part they laugh and carry on like the same two 19-year-olds who once headed into the great unknown together.

“Isn’t that unbelievable?” says Fitzsimons, those sentiments shared in the Balmoral striking a chord, “57 years ago…”

“And here we are now,” adds McCafferty, eyes narrowing as a smile spreads across his face, “still talking about it.”

***********************

THE world was a much smaller place in the Sixties. There was no trotting off across continents for Olympic qualifiers or global jet-setting for the World Series of Boxing. Instead, your business was taken care of on home soil – Ulster seniors, Irish seniors. This was the roadmap for any aspiring Olympian.

Flyweight McCafferty was pure class, dancing in and out of range to dominate opponents while Fitzsimons could mix it up either way; if you didn’t bring the fight to him, he’d take it to you, no invitation required.

The bull-strong featherweight, a protégé of Ulster and Irish coach Harry Enright at Short Strand club St Matthew’s, secured his spot by fighting twice on the one night at the National Stadium – first for a semi-final showdown earlier in the evening, then last between the ropes for a make-or-break decider.

“They kept me in the ring after my final to announce the team there and then. It was a great feeling to hear your name being called.”

McCourt, though… McCourt was something else. The Immaculata star, the sole medallist on the Tokyo boxing team after landing bronze, was unfortunately unable to join his former team-mates for a trip down memory lane, but his standing remains undimmed among all in Irish boxing circles.

“Och it’s a shame Jim couldn’t have come today,” says McCafferty.

“Jim was always the golden boy. He was a nightmare to box, a total nightmare. Jim was a computer before the computer started.

“If you were lucky enough to hit Jim McCourt twice, he made sure he hit you three times.”

“He was very, very smart,” adds Fitzsimons, who previously went toe-to-toe with McCourt before finding themselves on the same side.

“He was always an excellent body puncher as well - he had a fantastic southpaw left uppercut. Even as a juvenile I saw him knocking boys out to the body in the Down and Connor’s at St Kevin’s.”

Making up the five-strong team were Chris Rafter and Ballybofey’s Brian Anderson, a late replacement for Jim Neill after he was struck down with appendicitis.

Rafter, meanwhile, was a Dublin native stationed in Tokyo with the American army – the elder statesman on a youthful Irish team, having come up against the likes Belfast’s John Caldwell in bygone days.

“We had never even met him until we got out there,” says McCafferty.

Having been measured up for their suits at Austin’s of Divis Street, the team departed from Dublin airport and after a brief stop in Shannon, then a longer one in Alaska, their KLM flight landing in Tokyo days before the Games began on September 10.

“I nearly got arrested in Alaska,” smiles Fitzsimons, “I got off the plane and then realised I forgot my passport, so I ran back and was grabbed from all directions, 20 questions… I got the head chewed off me.”

Fitzsimons, though, might not have been there at all.

On June 13 his father, Harry, had dropped dead at just 48. For most of the next three months, his son lost interest. Pick somebody else, he told Enright, it’s not for me.

But Enright wouldn’t let it go – and Fitzsimons is glad he didn’t.

“My father, a big country man, ach he was so happy at me going to the Olympics. Anything to do with boxing at all.

“I left him on the Saturday, I’d gone to do a wee bet for him earlier in the day, and then me and Hannah were going to the pictures up at the Forum in Ardoyne when my name came up on the screen, asking me to come to the foyer.

“When I got out my uncle was waiting for me - ‘come on son, your da’s dead’. The last time I saw him he was sitting in bed reading the paper, happy as Larry. It near killed me.

“I was the oldest in the house and I wasn’t for going anywhere, I stopped training, stopped everything, but then Enright came round to the house, he kept on and kept on. Even when I said no, he’d come back again a few days later, always saying ‘you’ll do it for your da’.

“Eventually I did come back then…”

“And Harry was right,” adds McCafferty, “your father would have been glad.”

“He’d have been delighted; he really would. I know that now.

“Even when I got picked for the Empire Games in Australia, he drove us out to the airport just to watch the planes taking off. He was so proud.”

Heading Down Under was an experience of a lifetime, but Tokyo provided a glimpse of tomorrow’s world, leaving these starry-eyed Belfast boys open-mouthed at every turn.

“It was all built brand new for the Olympics, new roads, new buildings… it was like landing on a different planet,” recalls McCafferty.

“They had this interpreter looking after us - somewhere along the way he was christened ‘Tokyo Paddy’ - and every now and again he would’ve come up and put his arm round the back of your neck. You didn’t know what was happening, but he was taking photo with this wee hand-held camera.

“Then when you got into a taxi, there was a television in the dashboard…”

“This was 1964!” says Fitzsimons, eyes widening, “we’d never seen anything like that before.

“One day I went into a shop looking to get a wee present for one of the kids back home - a wee doll or something. The guy in the shop says ‘right okay’ and then calls this electronic dog over from the corner.

“This thing was reacting to his voice. I couldn’t believe what I was seeing, it was like witchcraft. But they were brilliant people, honest to God. Do you remember the day we got lost?”

“I do indeed, I’ll never forget it,” smiles McCafferty, Fitzsimons already primed to take up the tale.

“We were in this big store and came up level with the ground - or so we thought. We actually ended up underground somehow and on a train somewhere… we hadn’t a clue where we were going or where we’d come from!”

Fortunately all competitors had been given a badge for just such an occasion, with friendly locals only too glad to put them on the right track back to the former US army camp that was now the Olympic Village.

That was an eye-opening experience too, with athletes from around the world congregated in the one place - among them a man destined to go down in history among the greatest heavyweights of all time.

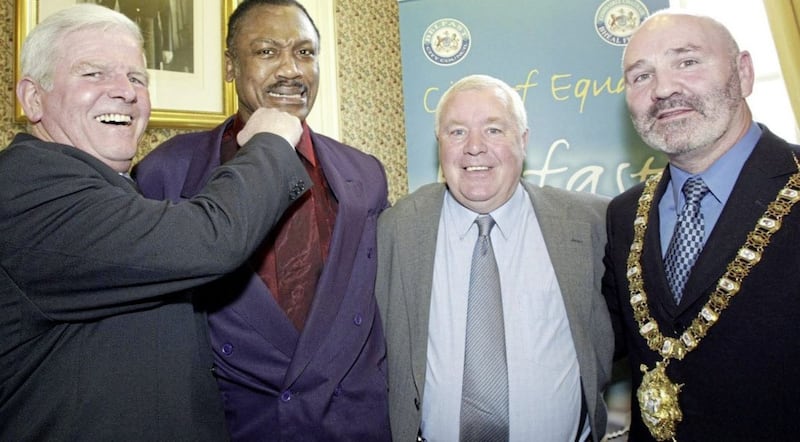

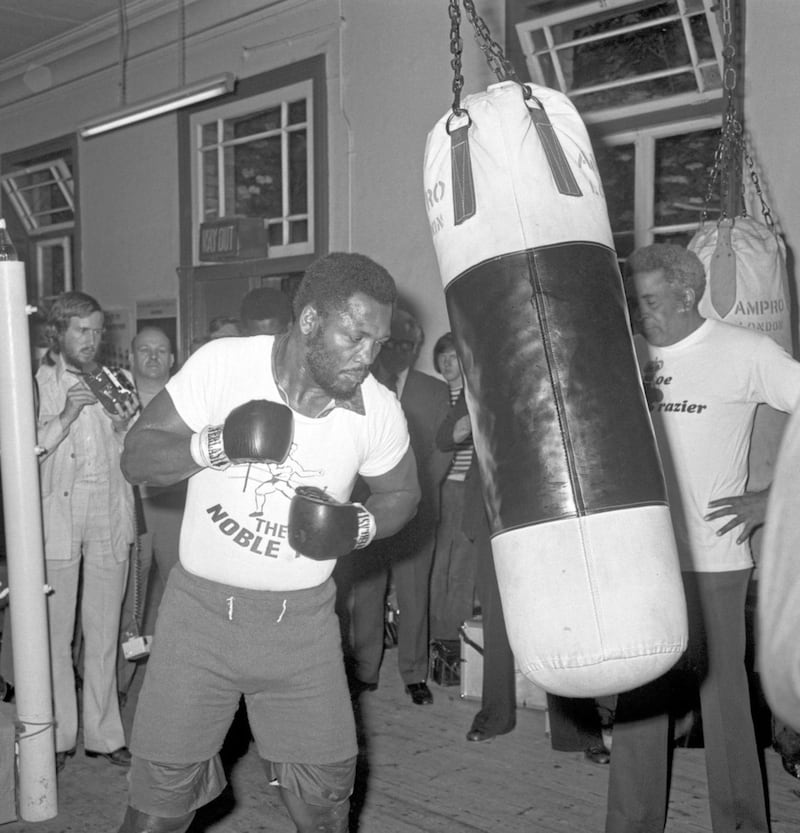

“We ran into Joe Frazier, not that you’d any idea who he was or who he would become. You were too young to really understand it, how amazing it all was. He’s got the earphones in, blaring away, telling us he’s going to turn professional after he wins these Games, no problem…”

Yet eventual gold medallist Frazier was only there because of the misfortune of his American rival Buster Mathis, the 300lb man mountain man who had beaten ‘Smokin’ Joe’ in the final of the US Olympic trials.

A broken knuckle put paid to Mathis’s dream, allowing reserve Frazier to fill the void - and Fitzsimons can clearly remember the day the drama unfolded.

“He put his hand through the heavy bag – I swear to God.

“We were training in a big gymnasium that was all partitioned off into different sections, and this one day all you heard was squealing and yelling. We went over to have a look and they were cutting his hand out of this massive hole in the bag.

“All of us were like ‘did you see that there? Jesus Christ…’”

“Frazier stepped in and was brilliant,” says McCafferty.

“At his final against the German [Hans Huber] everybody just stood up and clapped their hands for the whole three rounds - I never saw a fight like it.

“I came back home saying to a whole lot of people ‘this guy is going to be a world champ’ - but then you were only starting to hear about this other fella called Cassius Clay…”

***********************

HARRY Enright had his own charges well prepared for their own tilt at the big time too but, on a stage as big as the Olympics, only the strongest survive.

Anderson and Rafter both fell at the first hurdle, so too Fitzsimons, bowing out to experienced Pole Piotr Guzman at the Korakuen Hall – the trauma of the previous months, he believes, eventually taking a toll.

“I was disappointed because the fella I had beat in the Irish senior final in Dublin had beaten this fella, so I thought I’d be okay. But you’ve one shot and that’s it.

“It’s funny, you know what I remember about my fight, and it never happened me before? I heard them’uns all shouting,” he says, nodding towards McCafferty, “I could hear McCourt shouting ‘right hand, right hand’ - I was getting nowhere near the fella with a right hand.

“I lost concentration for the whole fight, my mind just wasn’t on it, and I think that went back to my da. I just wasn’t focused. Being honest, I couldn’t have cared less whether I won or didn’t.”

McCafferty had more joy, beating Cuba’s Rafael Carbonell and Ghanaian Sulley Shittu before being edged out by the eventual champion, stylish Italian Fernando Aztori, at the quarter-final stage.

“That fella was brilliant, but I’ll tell you what,” says Fitzsimons, “that was a very, very close fight. Nothing in it.”

“I don’t remember,” smiles McCafferty, “once you’re beat you try to forget about it as soon as you can.”

That left lightweight McCourt as the last man standing and, after dispatching the Korean Seo Bun-nam, Pakistan’s Ghulam Sarwar and Spaniard Domingo Barrera, he came out the wrong side of a split decision against relentless Russian Velikton Barannikov.

His bronze was the last Olympic medal Ireland would win until Hugh Russell in Moscow 16 years later, but Fitzsimons remains convinced McCourt should have finished further up the podium.

“To this day I would argue with anybody that he won that semi-final.

“Not long after that he beat Barannikov in Dublin, but I actually thought he won more convincingly in Tokyo. I thought he won every round, couldn’t believe it when the decision was announced.”

Barring a tour of the lower Falls Road organised by McCourt’s supporters, things were fairly low key when they got back to Belfast.

“Fair play to Jim, he asked us onto the lorry as well, but we just wanted to get home to see our own people,” said McCafferty.

“There was hundreds came out for him; it was brilliant of them to do that, and he deserved it. But we just got a taxi on home.”

And while the modern Olympian is cherished and looked after by the island’s various sporting bodies, the original Tokyo crew returned to work days later – Fitzsimons to the docks, McCafferty to his job as a paint mixer in Smithfield market.

“The only fanfare I remember after was being told by the brew I owed them four weeks’ money,” laughs Fitzsimons.

Both men would go on to give plenty back to the fight game, with McCafferty a central figure at the famous St John Bosco club through the years, still popping in when he can to lend a hand.

Fitzsimons, meanwhile, has been the beating heart of the Dockers club for as long as most care to remember, the love for the game still intact, so too a gratitude for all it has given them.

“You just get on with your life,” says McCafferty.

“He’s looked after clubs, I’ve looked after clubs… we’ve both put a good bit back into boxing and kept training kids.

“You wouldn’t have got to half the places we did without boxing, and it’s only now you realise how lucky you were. In those days, you’d nowhere else to go. It was either football, or boxing, so you did what you were asked to do and got on with it…”

“Maybe you hadn’t,” snaps Fitzsimons, “I’d everywhere to go – John Dosser’s, the Plaza, the Tudor Hall, Romano’s… we had about 15 dance halls to get around, every night of the week. Catch you yourself on!”

“It’s funny,” adds McCafferty, “the only thing I regret is not having a book or something with me to write down everything we did while we were there.

“That would be my advice to the ones in Tokyo at the minute - take a few minutes to write down what you’ve done every day, just something small, because you’ll be glad of it later in life.

“They’re memories you don’t ever want to lose a hold of. Take it from us.”