IT started with an email to a German casting agent back in May. Details were sent, request politely acknowledged and passed on – and then nothing. Discreet enquiries were made around the Belfast boxing scene too.

Some of the old guard had been chatting to him recently, others hadn’t crossed his path in years. But none had a number, or any clue where he was now. Sure if you see him, tell him to give me a shout? Yes, no problem, will do.

Days, weeks, months went by. Life moved on. And then, while away at the end of July, the phone rang.

“Hello,” comes a gravelly voice from the other end, barely audible above the waves crashing onto Whiterocks beach, “I think you were lookin’ me?”

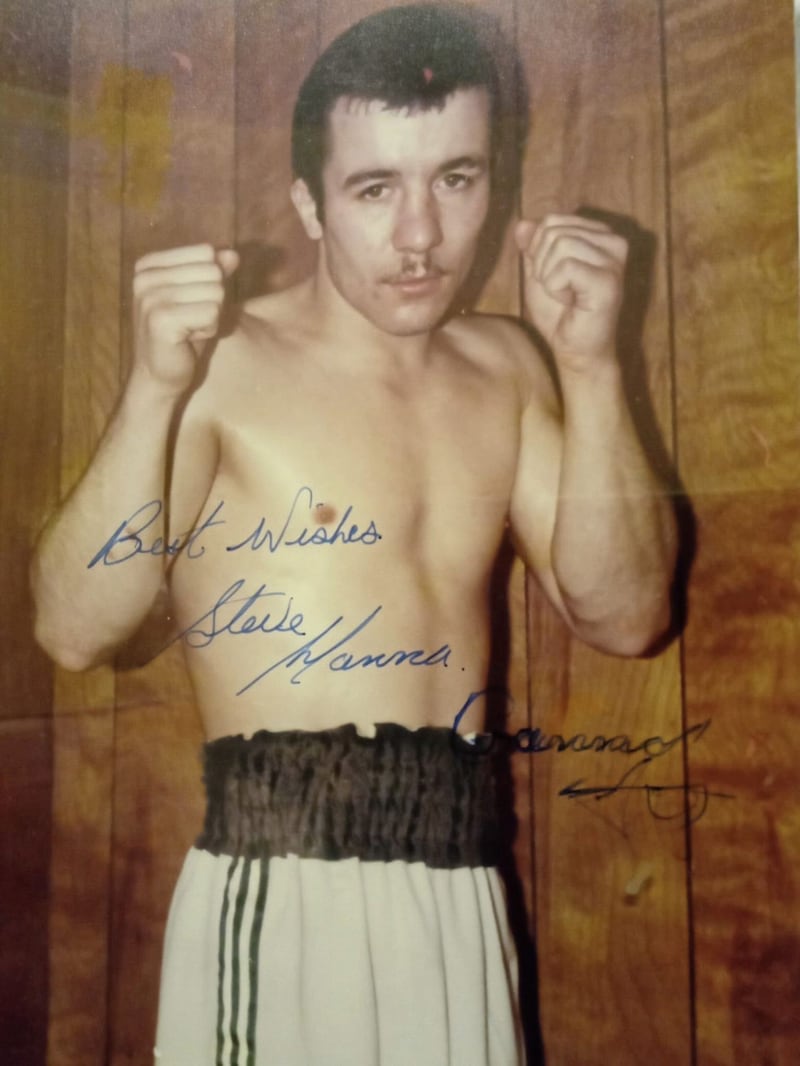

Meet Stephen Hanna – boxer, actor, artist, singer, guitar slinger, international man of mystery.

In the ring he was a stalking southpaw good enough to represent Ireland and reach finals night of the national senior championships twice during the early 1980s before sparring the likes of Barry McGuigan during a short-lived dalliance with the professional world.

Yet his relationship with the noble art is conflicted.

After initial scepticism (“I couldn’t honestly sit there and talk to you as though I had any kind of boxing career”), the phone buzzes out of the blue the morning after last month’s Feile fight night.

“What about McKenna?”

Now we’re getting somewhere. Tyrone McKenna, like Hanna, is a product of the Oliver Plunkett club in Lenadoon.

Standing 6”1 and blessed with long limbs, a lefty too, McKenna has all the tools to make life easy for himself against the smaller men at super-lightweight.

Sometimes he says he will, the odd time he does, but it is completely at odds with his instinct. After a cagey opening round against Mexican Jose Felix, McKenna decided enough was enough, bowing to the will of the Falls Park crowd, planting his feet and going to war.

By the time his hand is raised, having been dropping by a body shot in the third, swelling is forcing McKenna’s right eye to shut. Blood trickles down along his cheek and across his nose from a nick near the eyebrow.

The wide smile, soaking in the adulation, masks it all.

Hanna watched the fight follow its familiar pattern, gripped yet uncomfortable.

“I was probably a bit of a Tyrone McKenna, though Tyrone’s a far better fighter than I ever was,” he says over a coffee a few days later, raising his voice above the mid-afternoon traffic on Royal Avenue, a necklace bearing a small pair of golden boxing gloves sitting out over a black t-shirt.

“He was a cracking wee actor – did you ever see ‘The Mighty Celt’? Aww man, what a beautiful movie. The thing about McKenna is, while the rest of the fighters all hung around, he went off to America early in his career. That’s what makes him who he is today.

“And you can see it in him when he steps through the ropes. He loves the drama; he lives for it. I think I was a bit like that too...”

And as the conversation unfolds, you begin to realise why.

*************

STEPHEN Hanna had no intention of ever returning to Belfast. This time last year he was still in Berlin, the place he has called home since 1999. It was in the German capital that stage and screen ambitions started to take flight, new doors opening the longer he stayed around the scene.

Family circumstances have brought him back, for now. Earlier this summer his mother, Rosaleen, passed away. That came just a couple of years after the loss of father Hugh.

Without parents to anchor us, the world can seem a lonely place. It is a feeling Hanna has long wrestled with. Since being told he was adopted at six, there have always been questions and, now 61, the search for answers goes on.

“When you look at kids today, you’re always reflecting on your own upbringing. I was a very needy young lad. My oul lad ruled the roost. I wouldn’t have been a very confident child growing up, and I imagine all that played a part in it.

“Today, there’s a more enlightened way of dealing with that sort of thing. Back then… it wasn’t pretty. I suppose there’s an element that no matter how you doctored it up, however many ribbons you tie it up in, it still wouldn’t be pretty. To be honest, I remember even when I found the documents, I used to wish that it wasn’t true.

“My brother Paddy has Downs Syndrome, and it seems that when my mother was pregnant with him, the terms of my adoption hadn’t actually been settled.

“The doctor advised that maybe it might be best not to proceed, in the circumstances, but she disagreed. My mother would come to Nazareth Lodge and take me out for the weekend then bring me back.

“That happened for a long time, until eventually they took me home for good.”

And while he tried to find his way, boxing found him.

His introduction to the sport came when, on a whim, Hanna and a group of friends hopped into the van that used to ferry kids up to the old Oliver Plunkett club in Hannahstown. There was no prior interest, no posters on the wall – it was just somewhere to go.

From day one, it was sink or swim.

“Jimmy Finnegan, God rest him, used to put us all in the ring together and we’d all fight each other.

“I was terrified, all weights were in, big digs flying everywhere. It was madness. Jimmy was a great man, a hero who did a lot for the community in Lenadoon. He was a father, a man who was there for any fighter who needed a home.”

Hanna thrived on Finnegan’s one-to-one approach, and by his late teens had gone through a whole season without defeat, picking up an Ulster junior title along the way.

Within another couple of years he was competing against the best in the country, his first appearance on the screen coming on Irish senior finals night. But it never felt natural, or normal.

“I remember I was to fight Hugh Russell as a juvenile and, before one of the other fights, I saw this fella’s coach pushing him up into the ring. This guy didn’t want to be there. That unsettled me; my fear recognised his fear.

“You don’t need that, because the hard part about boxing is you go in there wanting to believe you’re Superman, only to find out you’re actually Clark Kent.

“That’s why I love watching the female fighters these days, because you can see they don’t have that machismo that men have. When they get instruction in the corner, they’re clear-eyed and they go out and put it into practice.

“Where for me, every time I got into the ring, it was a mess. A complete mess.”

Confidence, of a kind, didn’t arrive until his first pro fight in February 1984, a points victory over Shane Silvester on a Birmingham bill that also featured the likes of David Irving, Danny McAllister and future world champion, Dave ‘Boy’ McAuley.

“I went from featherweight as an amateur down to super-bantam… I didn’t care who I was fighting.

“That night it felt like I finally found the clarity to fight as a southpaw. I just waited, let him throw his punches, slipped them, then made him pay. I gave him a boxing lesson – three months later he went on to fight for the British title.

“As soon as it was over, I said to McAuley ‘you’re next’.”

Hanna bursts out laughing, recalling his affection for Dave ‘Boy’ before reliving some of punishing sparring rounds with the Larne man as trainer Paddy Maguire readied him for the pro ranks.

Barry McGuigan helped toughen him up too, the wince nearly four decades on telling its own tale.

“He hurt me with a body shot during a spar one time… oh my God. I thought I was going to have a baby there and then.”

Yet the story of Stephen Hanna the boxer would last for just one more fight – a points defeat to Keith Ward at the King’s Hall, four months after his debut, turning out to be the final curtain call.

It wasn’t that he had fallen out of love with the game, because it had never taken hold of him in that way. It was just time to go, time to leave Belfast behind and find something new.

Next up, London was calling, and the pursuit of a passion that had fired a fertile imagination through the darkest of days.

*************

IT’S the Saturday evenings he remembers best. Paddy next up on the sofa, their dad in the armchair, all glued to the screen. Day by day, the chaos of the Troubles was tightening its grip on the streets around him, but the characters, the stories, the ability to slip off into another world, even just for a couple of hours, it brought joy where little else did.

“I always loved movies… it was the only real thing me and my oul lad had in common. With the boxing, it was a case of – and he was right – I wasn’t doing the things you had to do to be a boxer. I wasn’t being the body beautiful, I wasn’t living the life.

“Paddy would sit there, not saying a word. My da would be the same. Not a peep. That’s where peace was; the only time when the house was calm and everything was okay.”

When alone in his room, Hanna would immerse himself in the Tom Sawyer novels, imagining himself as Tom’s trusty sidekick, Huckleberry Finn.

And when an aunt in Canada sent a copy of Charles Dickens’s A Tale of Two Cities over to Belfast, it helped alter the course of a young man’s life for good.

“They put me into a very low class at St Mary’s after I failed my 11 plus. There were boys with moustaches they’d been there so long, and they were still in first year. I knew I shouldn’t have been there – it was like going into a prison.

“We had only one teacher and he never gave us any work, we all just sat there, everybody was bullying each other… it was terrible. I needed out of it, and one day that teacher wasn’t in, so they brought in a Brother. He was known as ‘Brother Brassneck’, and had a reputation for being wicked if you messed around.

“This day he came in and said ‘we’re going to read a book called A Tale of Two Cities, I wouldn’t expect any of you dodos to actually know anything about it’. So I put my hand up and said: ‘It was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of light, it was the season of darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair’…”

‘Brother Brassneck’ took Hanna straight down to the headmaster’s office and had him moved up in class.

“That book saved my bacon.”

When the gloves were finally hung up, he came back to his first love. London was liberating, the complete opposite to the claustrophobia Belfast inspired.

It was there he met the mother of his son, Joseph James. Life was good. But eventually he came back to do a theatre studies course as a mature student at Rupert Stanley College. If he didn’t give it a shot now, he never would.

“If you’re a person who can step up and step into a ring, you’re definitely a person who can step onto a stage. It’s probably more of a needy thing than confidence. Maybe it’s craving attention.

“One of the first productions I was ever involved with was West Side Story. Because I was playing Pepe, one of the Puerto Rican guys, I was learning bits of Spanish and talking away in that accent.

“There was one night I was heading home from rehearsal when the British Army stopped me on the Falls Road. I had curly hair - I think I might even have been in costume - and the soldier said to me ‘what’s your name?’

“Hey,” says Hanna, animated all of a sudden, mimicking the Hispanic accent from the Shark gang’s second in command, “my name is Pepe. I come from Puerto Rico. And the soldier was like… ‘you wot?’

“Eventually he let me go. These three other guys were already standing with their arms up against the wall - I knew one of them. When I gave him the thumbs up he had a big smile on his face.”

Hanna hasn’t looked back since those early steps along the boards. But it wasn’t until the intervention of fate, and faith, that the pieces scattered elsewhere began to fall into place.

“Everything changed in Medjugorje,” he says.

“I had just turned 40, I spent a lot of time on my own there, and I asked our Blessed Lady to bring my son back into my life, and I asked her for a partner to share my life with. I left a picture of my son at the statue and walked away.

“Honestly, I believe it was our Blessed Lady who brought me to Berlin…”

And when he did go, he was not alone. This is where fate comes in.

After reluctantly accepting the gift of a puppy from a Belfast barmaid, Hanna named the dog Berlin.

“I don’t even remember why…”

A year later, on the way to Knock shrine, he got talking to a German lady, a journalist there to write a piece on the pilgrim walk. A long distance relationship followed.

“And then,” he smiles, “me and Berlin went to Berlin.

“It’s one of my big regrets that I didn’t go there earlier. The people, the way of life, the languages you learn… your brain just grows with everything that’s going on around you.

“But now, here I was, back in contact with my son, I had a partner who appreciated me. I’m not sure I’d ever felt that before, but it’s better to have it happen at 40 than to never happen.”

Hanna would go on to feature in countless theatre productions across Germany during his time there, regularly popping up on the silver screen too - even appearing in Ronald Emmerich’s $30m 2011 period drama Anonymous.

“When you get a line in a movie like that… that’s the right hook.”

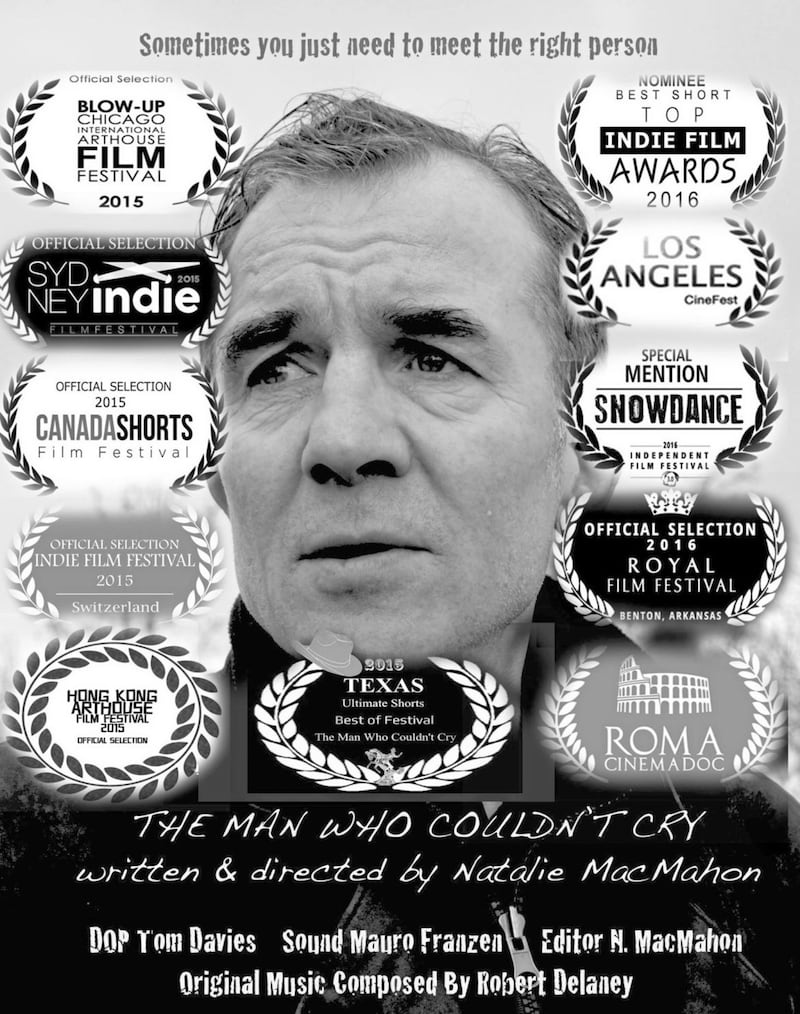

His role in the 2013 film Berlin Junction is the one that makes him most proud, while Hanna was widely lauded for his performance in the award-winning short, The Man who Couldn’t Cry.

When he looks back across his career, every story, every role has given him something. And boxing was there all along too, it still is, even if the final bell has long been rung.

“I did a workshop a few years ago with Aida Turturro [who played Janice Soprano, Tony’s sister, in The Sopranos]. She was talking about the preparation for a part, and it all sounded so familiar.

“It seemed to me that was what I was doing quite a lot as a child, preparing to go and fight, was a very similar process to acting. You go up into your room, you get your bandages, you roll them up, you get your towel, all your gear… for a long time I just had a wee VG plastic bag to put it into.

“And what went into that bag was whatever amount of fighter I had in me. And then, at the end of it all, there’s those three steps, up to the ring, and you’re on stage…

“People only see the fighter in there, but boxing teaches you a lot about life, nothing moreso than you get knocked down and you get back up again. No matter what happens. That’s what it’s all about.”