NOT for the first time, history awaits Katie Taylor. In the early hours of Sunday morning, she will be the A-side in the first female headliner at Madison Square Garden, breaking new ground at boxing’s most storied venue after 140 years hosting the great and the good.

It won’t take place at the smaller Hulu theatre either, but upstairs. The big room. The place where Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier went toe-to-toe in the ‘Fight of the Century’, Rocky Marciano and Joe Louis 20 years before that – ghosts of greatness everywhere you turn.

The Garden isn’t quite a sell-out yet, that could happen by the time the doors open tomorrow, but the battle to become undisputed lightweight queen recorded the second biggest pre-sale in the venue’s history when tickets were released earlier this year.

An estimated 4,500 fans are travelling to New York from Ireland and the UK. The fact it is a pay-per-view event also ensures both women are guaranteed seven-figure purses – another first.

This is a watershed moment for women’s boxing, and for Taylor. But she, more than anybody, is acutely aware of the many barriers that had to be broken down to get here; her own remarkable rise from amateur star to professional standard-bearer only a part of the story.

Think of the biggest days in Irish sport – the penalty shoot-out win over Romania at Italia ’90, Michael Carruth’s Olympic gold medal in 1992, Taylor following suit in London two decades on. This weekend could join the list too.

March 2, 1997 doesn’t feature much in the conversation. It doesn’t feature at all, truth be told. Yet 25 years ago, Deirdre Gogarty became Ireland’s first female world champion at the third time of asking, defeating Bonnie Canino to claim the IBF featherweight crown.

That show played out before a meagre crowd at the Lakeland Arena in New Orleans, and took place way down the undercard.

Still, it secured Gogarty the biggest payday of a seven-year career that saw her leave Drogheda for the US because females weren’t allowed to box in Ireland - and that’s before you even get near the blood, sweat and tears required to simply stay active.

The purse? $12,500. And even then there is an asterisk.

“You know I never got paid for that?” she told me, “no, we never got a penny. Nobody on that card got a single cent. The promoter, I dunno, he claimed he didn’t bring in enough money to pay anybody.

“So the biggest purse of my life, and I never saw any of it.”

Yet having her hand raised that night meant more than anything money could buy.

Gogarty may not have been splashed across newspapers back home, no crowds gathered at the foot of the airplane steps next time she touched down in Dublin, but it was vindication for dedication to a dream that began in her bedroom.

Inspired by Barry McGuigan, Gogarty snaffled a large blue bag from her father’s workshop and stuffed it full of foam, old clothes and newspapers before hanging it in the wardrobe. Far from prying eyes, she would let rip with punches, pretending she was in Madison Square Garden rather than Mornington.

An orange peel didn’t quite have the cut of how she imagined a real gumshield would feel, so instead a white candle was melted and rolled before eventually being molded around her teeth.

After eventually being allowed to train at Drogheda and then St Saviour’s boxing clubs, her first (illegal) fight took place in the beer garden at the back of the Shannon Arms pub in Limerick.

As the heavens opened, she found herself stepping over mud puddles on the way to a makeshift ring.

After her second underground fight months later, Gogarty sent off letters to managers and promoters across the US, begging for a chance. Very few responded. Of those that did, topless boxing and mud-wrestling were the options on the table.

Louisiana trainer Beau Williford, an imposing ex-heavyweight who once sparred with Muhammad Ali, eventually reached out and offered an opportunity that would change her path. Yet even then it was made clear – the men in the stable come first.

Gogarty sparred countless rounds against them all in a run-down chicken shed in Lafayette, where the already unbearable heat was cranked up by a crawfish boiler bubbling over in the corner.

The landscape, in terms of female boxing, was light years from where we stand now – a fistful of dollars often the most she would make after weeks of painstaking work.

“It was the fear that it would be an embarrassment, a sideshow, a novelty act, a catfight… there was a lot of resistance,” she said.

“You had old school boxing promoters, and it just seemed to turn their stomach.”

Yet back home, a new admirer was following her journey.

A young Katie Taylor devoured any coverage that came Gogarty’s way as her career progressed – if this woman from up the road can do it, why can’t I?

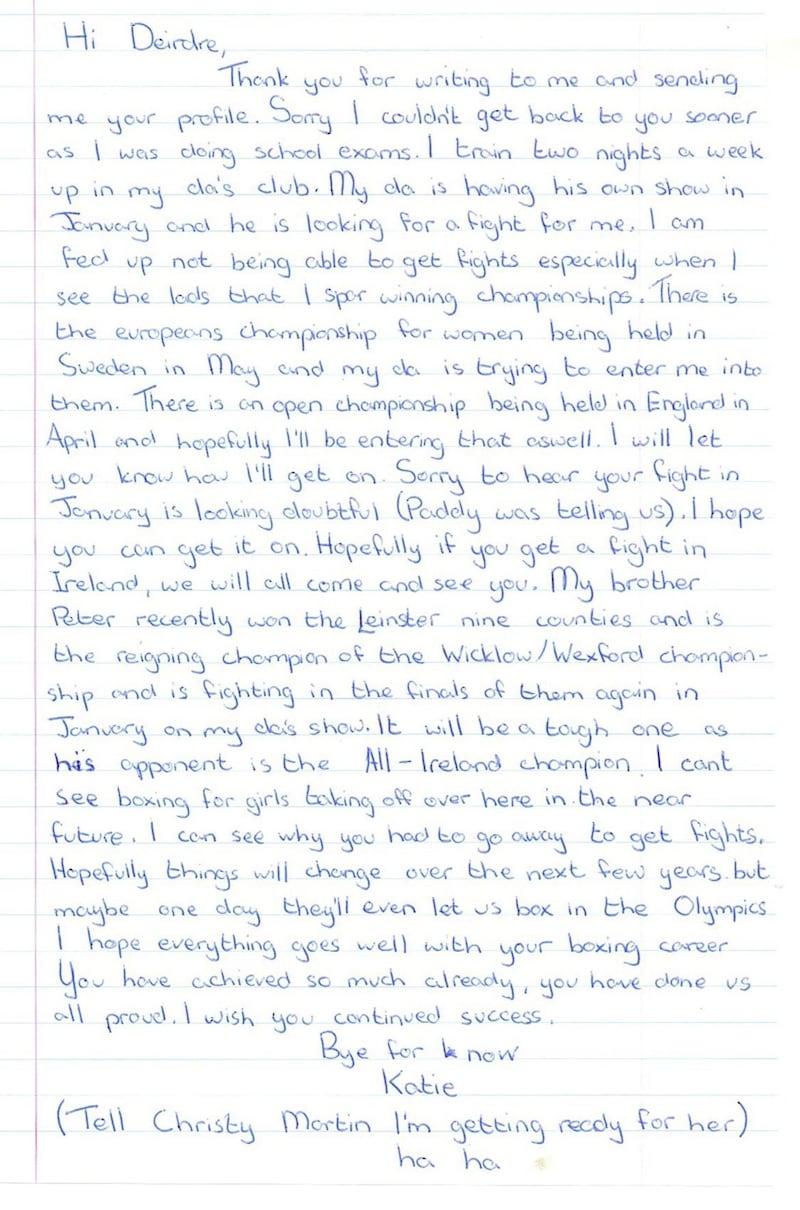

That’s why Gogarty still treasures a letter from the 10-year-old Taylor.

It arrived in the months after her historic 1996 showdown with Christy Martin on the undercard of Mike Tyson-Frank Bruno II in Las Vegas, while Taylor – along with father Peter – would later visit Gogarty on a return trip to Ireland.

Quiet and shy, just like her hero, Taylor would tuck her ponytail under a headguard and pretend to be a boy so she could trade leather in Bray. Yet, with acceptance still so far off in both the amateur and professional worlds, the shared sense of despair was clear when she put pen to paper.

“I am fed up not being able to get fights, especially when I see the lads that I spar winning championships,” she wrote.

“I can’t see boxing for girls taking off over here in the near future. I can see why you had to go away to get fights. Hopefully things will change over the next few years… maybe one day they’ll even let us box in the Olympics.”

Five years after sending that letter, Taylor's persistence paid off as she ducked between the ropes at the National Stadium to face Belfast’s Alanna Audley in the first sanctioned women’s fight in Ireland. Her brilliance thereafter ensured the men in suits at the very top of the game could no longer turn a blind eye.

Eventually, with Taylor’s status key, women were allowed to box at the Olympics – and when they did so for the first time at London 2012, she was the star.

Ten years down the track, and now 35 years old, Taylor is still there, front and centre, kicking down walls and dragging the sport along with her.

Yet the sense of gratitude to those who sailed choppy seas before has always been there - sympathy for the struggle even as she holds history in her hands once again.

“I’m also very grateful for the women that went before me – the likes of Christy Martin and Deirdre Gogarty, Lucia Rijker, Laila Ali who were pioneers in their sport,” she told reporters earlier this week.

“I don’t think I’d be in the position I’m in today if it wasn’t for all those girls.”

For keeping up the fight and continuing to make their voices heard, even in a world unprepared to listen, their contribution should never be forgotten.