THE scene could have been scripted by Flann O'Brien: policemen on bicycles puffing through the backroads of county Monaghan on a warm summer's day, chasing a contingent of at least 32 cyclists who, somewhat strangely, looped three times around Newbliss before heading on home to Clones.

Perhaps O'Brien would have called it 'The Tired Policemen' or, knowing his love of puns, 'The Tyred Policemen'. Yet although this comic tale from the summer of 1918 had a darker twist typical of Flann's writing, it did actually happen.

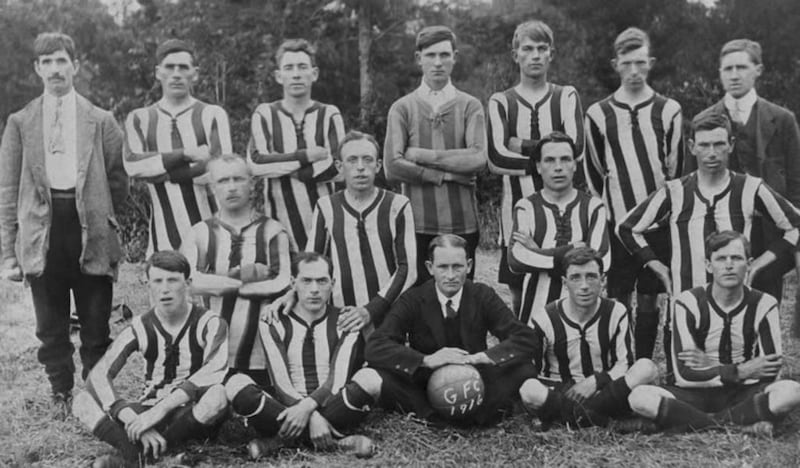

The Clones-bound contingent were returning home from the re-fixed Ulster SFC semi-final between Cavan and Armagh at Cootehill, which the home team won by 2-4 to no score. The cyclists were 'tailed' by memvers of the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC).

One of the cyclists recalled the events years later: "As we pedalled along, on the return journey, we saw that an 'escort' of RIC men, also mounted on bicycles, had been sent after us. The temptation to have a little fun at their expense was irresistible.

"Instead of taking the direct homeward route out of Newbliss, we took a little bye-road which led back eventually to the village. The RIC men toiled after us, on their heavy official machines, less athletic than were the Clones lads for this or any other sport, under the warm sun of July.

"Three times the unfortunate constables found themselves doing a circular tour of Newbliss after us."

The leaders of that cycling group, Eoin O'Duffy and Dan Hogan, were later arrested and sentenced to a couple of months in Belfast Prison for unlawful assembly.

O'Duffy at that time was Ulster Council Secretary and Tipperary native Hogan, who lived in Clones then, was the match referee.

Fine Gael and Blueshirts

Both went on to greater fame, or infamy in the case of O'Duffy. Rising to IRA Chief of Staff in January 1922, he then became Garda Commissioner, before lurching into fascism with the Blueshirts and being the first leader of Fine Gael. He even went with an Irish Brigade to fight for Franco in the Spanish Civil War.

Hogan – whose brother Mick was one of those killed in Croke Park on 'Bloody Sunday' 1920 – rose to be Irish Defence Forces Chief of Staff in the late Twenties.

O'Duffy's merry tour around Newbliss has often erroneously been reported as following the initial forced cancellation of that Cavan-Armagh Ulster SFC semi-final in July 1918.

Yet the confrontation in Cootehill on July 7, 1918 undoubtedly was one of the major sparks which led to Gaelic Sunday spreading like a fire – a very well-organised fire - to cover much of Ireland.

"When we refused to take a permit for the Ulster Senior Football Final at Cootehill, fixed for July 7, 1918, the match was 'proclaimed' [i.e., declared an illegal assembly] and when the game was due to begin the field was in possession of a big detachment of military, fully armed," recalled O'Duffy.

The forces of 'law and order' were under the command of an RIC Inspector McEntee, who, the Freeman's Journal reported, "intimated that forcible methods would be used if the match was persisted in".

As O'Duffy remembered, "It was impossible to play owing to the danger of tripping over some 'Tommy's feet, or of falling on a bayonet…"

The FMJ reported an attendance of 5-10,000 , the then unionist 'Northern Standard' said 'hundreds', so the probable 3,000-strong crowd of spectators marched into Cootehill where the local parish priest, Fr O'Connell, addressed them, "exhorting self-restraint and to return home quietly". He had been Arthur Griffith's election agent in the recent East Cavan by-election won by the Sinn Fein founder, so the PP held considerable sway in the area.

The crowd followed Fr O'Connell's advice and dispersed peacefully so O'Duffy and the Ulster Council re-fixed the match for the same venue, and it duly took place – but more than a month later.

The game went ahead on Sunday August 18, perhaps because of the intervening influence of 'Gaelic Sunday', although it still did not pass of without incident, before Cavan won by 2-4 to 0-0, as O'Duffy remembered.

"This time it was a force of armed RIC men who attended, but they were rather fewer and less formidable, and there were no projecting bayonets."

The RIC also "had their revenge" for O'Duffy and Hogan's wheeze of exhausting the 'escort' around Newbliss afterwards.

"Like any cycling club, the Clones contingent obeyed whistled orders from Dan or myself – for instance, as to mounting or dismounting on hills.

"At six o'clock next morning Dan and myself were taken from our homes by RIC supported by military and solemnly charged with 'unlawful assembly, by leading a procession of cyclists from Clones to Cootehill and back and blowing whistles as signals for mounting and dismounting'.

"We both refused to give recognisances for future 'good behaviour' to the would-be reasonable resident magistrate and duly spent a couple of months in Belfast Prison."

Read more:Part one of the series - 'Gaelic Sunday' 1918: When GAA opposed British oppression

Authorities increasingly suspicious of GAA

The authorities were increasingly suspicious of the GAA in 1918, states historian David Hassan: "A range of very prominent GAA people, like O'Duffy and Harry Boland [who refereed the 1914 All-Ireland SFC Final], were leading a double life, actively involved in more militant aspects of revolutionary politics, advocating military resistance.

"In June and July the British start to agitate much more against Gaelic games and the Association was feeling mal-treated."

Since the introduction of the prohibition on public meetings without permits at the beginning of July, there had been numerous reports of interference with GAA fixtures throughout Ireland.

Games disrupted

Later that month police had charged at a crowd gathered to watch a football match in Ballymena, and apparently attacked players assembled to take the pitch at a match in Kerry.

The RIC noted down names of spectators and players at a junior football match in Castleblayney and even arrested nine boys playing a game in Dublin's Phoenix Park.

In Tyrone by the end of June, when most of the league games in both divisions had been played, Omagh O'Neills (who in January had won the Erne Cup), were declared winners of the West Tyrone League, while Cookstown Brian Og, who had won the 1917 county football championship, emerged victorious in the East Tyrone League.

At a meeting of the County Board held on June 30, it was decided to play the county final at Dungannon on Sunday July 21. However, the match does not appear to have been played on that date, however, due to the July 4 proclamation, with GAA officials warned that the match would not be allowed to be played unless a permit was received.

With all this disruption of games, the GAA held a special Central Council meeting at its offices at 68 Upper O'Connell Street, Dublin on July 20, 1918.

The meeting, at which there was a full attendance and at which President James Nowlan presided, having been released from internment in Frongoch after his arrest earlier in the year, was summoned to consider 'how to proceed with the organisation of matches in light of the existing conditions in the country.'

'Gaelic day' proposal

Perhaps significantly, the proposal for a 'Gaelic Day' came from the Ulster Council, according to Sighle Nic An Ultaigh in 'An Dun, O Shiol go Blath, The GAA Story'.

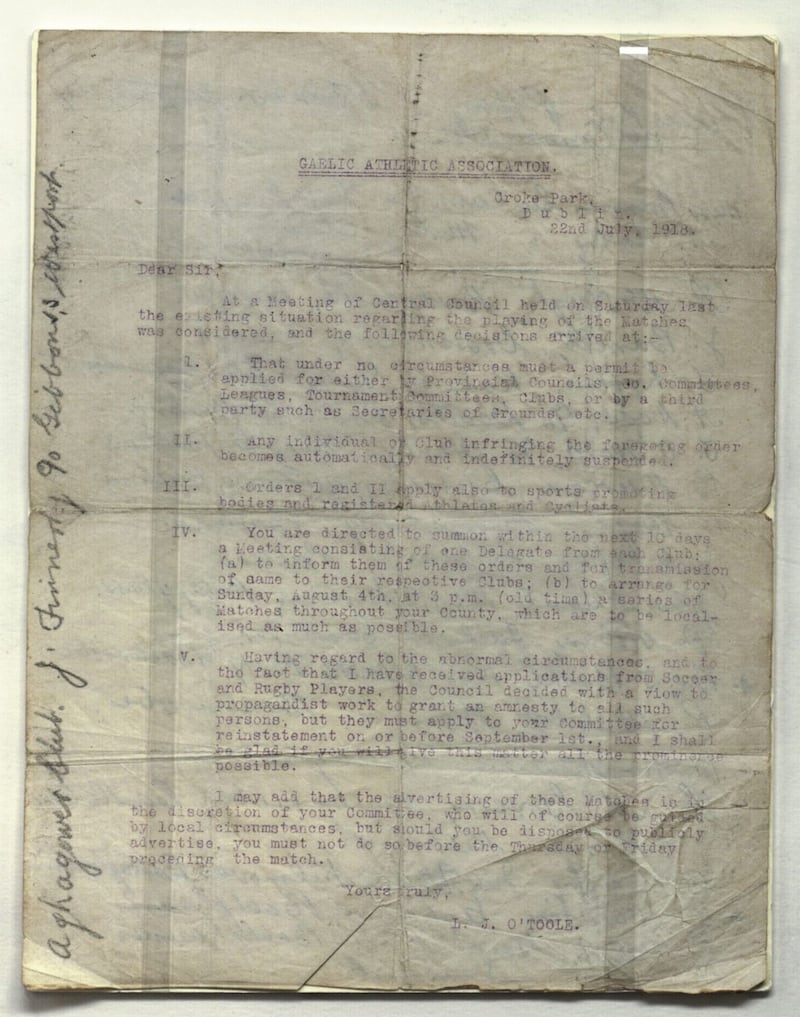

Central Council ordered that "under no circumstances must a permit be applied for either by provincial councils, county committees, leagues, tournament committees, clubs or by a third party such as secretaries of grounds etc."

The penalty for infringing this order, for a club or an individual, was indefinite and immediate suspension. The second part of the missive, though, was massive:

"You are directed within the next 10 days to summon a meeting consisting of one delegate from each club: (a) to inform them of these orders and for transmission of same to their respective clubs; (b) to arrange for Sunday, August 4th at 3pm (old time) a series of matches throughout your county, which are to be localised as much as possible."

Amnesty for players subject to 'The Ban'

In the letter on the subject sent out by Luke O'Toole, the first full-time Secretary-General of the GAA, was also an often-overlooked aspect of the GAA's approach – an amnesty offered to all those who wished to return to the Association after falling foul of 'the Ban' on participation in 'foreign games' such as soccer and rugby.

According to Hassan it was a case of "all were welcomed back, it was essentially 'all hands to the pump', let bygones be bygones and let's move on.

O'Toole wrote: "Having regard to the abnormal circumstances, and to the fact that I have received applications from Soccer and Rugby players, the Council decided with a view to propagandist work to grant an amnesty to all such persons but they must apply to your committee for reinstatement on or before September 1st., and I shall be glad if you will give this matter all the prominence possible."

However, O'Toole did advise county boards, clubs, etc, not to advertise any planned matches before the Thursday or Friday of the first week of August. Clearly interference from the authorities was still a factor to fear.

Hassan feels that "both the Central Council determination and subsequent ones made by various county boards were almost like the flicking of a switch – the GAA had been passive, then all of a sudden there was this resolute determination that they would not stand for it any longer.

"People sometimes think 'Gaelic Sunday' precipitated the decision to remove the ban on mass gatherings – but that came before, almost as if British saw what was coming down the tracks in terms of mass opposition."

Keeping politics OUT of sport

The GAA wasn't 'the IRA at play', as has been the jibe from unionists/ loyalists at times, in fact Hassan agrees with the suggestion that 'Gaelic Sunday' was actually about keeping politics OUT of sport:

"Absolutely, that's the essence of our argument. Other historians and commentators, and the Association itself, were too quick to position the organisation as an associate element of the military or political uprising.

"For the most part, the GAA was a cultural organisation, it played games. It had amongst its membership, unquestionably, people who were also involved in these other activities, but as an Association itself, even in that second decade of the 20th century it was a virtual political bystander – with the exception of Gaelic Sunday.

"Yet when people write the history of that period Gaelic Sunday still barely gets a mention, because it's almost the exception that proves the rule. Eventually the GAA finds its voice."

The British heard the message loud and clear. Hassan and McGuire noted that "Throughout the first week of August, newspaper reports outlined the government's new position on Gaelic matches.

"It came to light that the authorities sent a circular around to the police outlining how Gaelic matches were no longer considered to fall under the restrictions of the proclamation. Previous police interference in matches was said by Secretary Shortt to have been a result of police who 'had unfortunately misunderstood their instructions'".

IPP leader John Dillon was cynical about this rather Trumpian explanation of a 'curious telephonic mistake' and told Parliament that the enforcement of a ban on social gatherings and public meetings was "greatly to the annoyance of the people of Ireland, where the feeling is extremely bitter and exasperated."

Having forced the British to back-track, why did the GAA go ahead with 'Gaelic Sunday' anyway? Partly because plans were already in place, but mostly perhaps due to its propaganda value. A 'Meath Chronicle' editorial said that 'every Irish man and woman worth of the name is expected to patronise in some practical manner their national pastimes'.

Hassan and McGuire opine that "Gaelic Sunday was to be used as a show of cultural nationalism so that the authorities might know not only the seriousness with which the GAA viewed the ban on Gaelic games, but also the sheer numbers of people and the clout which it had at its disposal. The importance of Gaelic games within society necessitated that those who treasured Irish culture take the opportunity to stand with the GAA."

While the First World War was coming towards its end, there was a growing cultural war within Ireland, leading towards the War of Independence breaking out in 1919.

Gaelic Sunday undoubtedly played its part in that movement.

Read more:Part one of the series - 'Gaelic Sunday' 1918: When GAA opposed British oppression