THE shake of the head and shrugging of shoulders are almost apologetic; a mixture of wearied exasperation and awareness that a familiar drum beat is about to sound.

From rule-makers to rule-breakers, Kieran McGeeney’s musings about the nitty-gritty of GAA officialdom and occasionally inexplicable decisions are generally measured and considered, yet you needn’t always scratch too hard at the surface for his truth to out.

The definition of the tackle, or lack thereof, has long been a stone in his shoe. What constitutes hard but fair and what is a foul?

With that in mind McGeeney, not one for donning sepia-tinted specs, might find it hard to suppress a smile - possibly even a swelling of the chest - as Sherman Hall recounts his first-ever experience of Gaelic football.

“I had come over from the States in 1989. So this was maybe 1990 or thereabouts, and Forkhill were playing Mullaghbawn in Forkhill. It might have been a friendly game, I don’t remember, but I was standing right on the sideline, trying to follow what was going on.

“Next thing I look up and Kieran McGeeney hits one of the Forkhill players with an absolute bulldozer of a shoulder. He milled him man, just milled him...”

The Forkhill player landed right on the chalk beneath. Hall remembers looking down towards the stricken body at his feet, then up at McGeeney, moving purposefully back into position.

“Shitttttttttt,” he thought, a surge of electricity shooting through his core.

“I love this game!”

Hard but fair, and nobody was about to argue.

Brought up in a die-hard American football household, Hall could never have imagined feeling so at home, so far away.

Almost 30 years on from that afternoon at Pairc Ui Dhoirnin and All-Ireland winning captain McGeeney is now manager of an ambitious Orchard squad that counts Sherman’s son, Jemar, among its number.

Hall senior is involved in coaching the Orchard Academy U15 squad and, when he can, helps out with a fledging American football team, the Louth Mavericks.

Yet to most around the Newry area, and at St Oliver’s Community College in Drogheda where he has worked for 19 years, Hall will always be ‘the basketball guy’.

He still takes groups of kids all week in school and on Saturday mornings at Newry Leisure Centre, teaching them the fundamentals of the game.

Increasingly, though, he is finding the rest of his weekends governed by football. If Armagh are playing Meath in Navan, then that’s where he’ll be. If it’s a trip to Ballybofey on a stinking wet Saturday night, as was the case a few weeks back, Sherman Hall will be there in the stands.

Words of advice are offered only when asked for on those long journeys home, the gentle rumbling of rubber on road enough to pass the time.

The father gets it; once upon a time it was him looking out the window at the night sky reliving every play, smiling at the good memories and shuffling uncomfortably at the bad, all part of the pursuit of a sporting dream.

****************************

ROCKVILLE, Maryland - about 16 miles outside Washington DC. Go there now and you will find a city that is typical of almost any other suburban outpost; a haven of high rises and huge shopping centres.

But the Rockville of the ’60s and ’70s, the one Sherman Hall knew, was very different.

His grandfather had a farm out in Poolesville where the family would take friends to show them what rural living really was. Thinking back, it could just as easily have been south Armagh.

“I’m a country boy. Back then it was rolling fields, cow sh**e and everything that goes with it,” he says in a thick American drawl that contains only the odd fleck of Forkhill.

Hall was born in 1956, just as the American civil rights movement was beginning to gather momentum but still nine years away from the abolition of the Jim Crow laws that enforced a form of racial apartheid in the southern states.

His father Frank was a US army drill sergeant, mother Suzie a teacher, and Hall’s childhood memories are of long sunny days spent playing with the other kids in the area, regardless of colour or creed.

And while America was changing, sport could still serve as a unifying force even during those troubled times. Thankfully for a young Sherman Hall, it was a world in which he excelled.

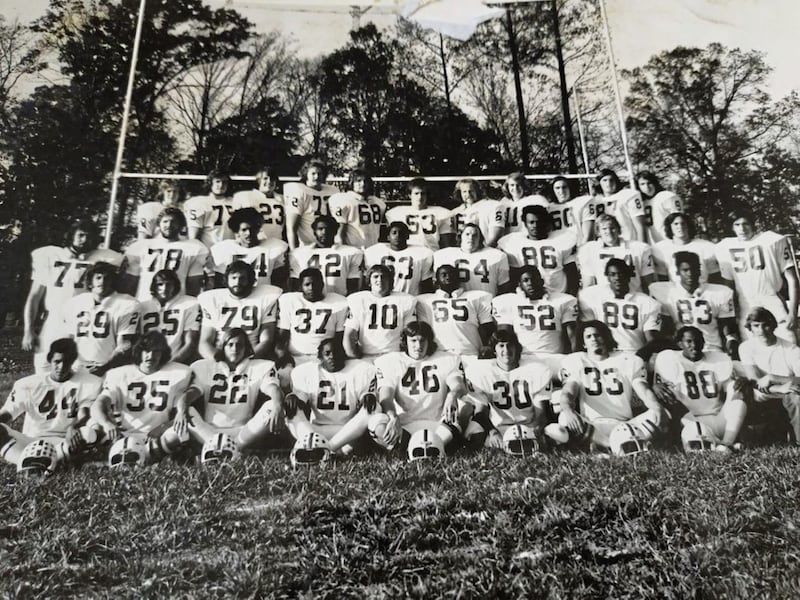

Standing “six foot even” and naturally athletic, he starred at basketball, baseball and American football, soon making a name for himself as a jet-heeled wide receiver at Richard Montgomery High School.

It was here that Hall began to appreciate the role a coach had to play, instantly name-checking one early influence in particular.

“Kanesky,” he grins, shoulders shuddering up and down as his mind travels back in time.

Mike Kanesky was an ex-military man like Hall’s father but, beyond the abrasive, Full Metal Jacket veneer, he had an aptitude for dragging the best from young men right across the board.

“Before a game he would come in and make this big speech. The boys would warn you not to sit at the front – he would start throwing shit, getting all fired up, getting the whole team fired up.

“He was a great motivator but, when he needed to, he had a soft side. He could say ‘so what you’re not playing well; give me something next week’, or ‘give me something in training’.

“He wanted you to enjoy what you were doing, to enjoy playing and to make the most of what you had.”

Hall did just that, and was offered a scholarship to Knoxville College in Tennessee where he completed a degree in elementary education, making him a qualified international teacher.

But he wasn’t ready to trade the football field for the front line of the classroom just yet.

A deal was agreed to play for a semi-pro side called the Frederick Falcons, a nursery club or ‘farm team’ for NFL giants the San Diego Chargers. So the big time was finally within reach?

Well, not quite.

“Ahhhh man, you don’t wanna know!

“At the time my ambition was to go all the way. I wanted to be on TV, I wanted to play. I wanted to be in the limelight. It’s a great feeling coming out from the locker room and there’s fans screaming and you don’t hear nothing but aaaaaaahhhhhhh...

“I got paid good money but it’s not always what everybody thinks it is - just because a team like the Chargers is monitoring you doesn’t mean they’re gonna take you.

“I was sent there to develop to where they wanted to play me. If I had’ve come through the NFL Europe generation, they would’ve sent me to Europe to play, but this was in the States and you played in this league where you travelled on a bus, you lived out of a suitcase… it was f**kin’ horrible.

“All you want, all everybody wants, is to get to the big show; to go out to California to play out there, play in warm weather.

“That doesn’t happen for too many guys; you’re told that on the first day. I remember coming back one day after training and this guy who was playing with us, they shipped his ass off to North Carolina.

“Literally, you could find a tag on your locker that you’d been sold – that’s how cut throat it was. We had to take him straight to the airport and all the stuff from his apartment was on the plane already.

“They put him in a hangar, it wasn’t even a seat! He could see his stuff, everything he owned, and he was on his way to North Carolina. That’s it. Even when you play with the big clubs, your ass gets sold, you gone.

“Ah man, it was bad. I’m telling you it was bad. Imagine travelling from the east coast to the west coast on a Greyhound Bus for two days, stopping in the Arizona desert taking a piss, looking up and saying ‘what the f**k are we doin’?’

“But you’re young and you don’t care.”

The dream of making it to the big show drifted further from view with each year that passed, before all hope was ripped away when Hall suffered a devastating back injury just short of his 24th birthday.

“I got flipped in the end zone and I couldn’t feel anything in my toes or my legs.

“I was just… numb. Numb from the waist down. I still remember the doctor coming to me and saying ‘son, continue playing if you want to end up in a wheelchair’.

“Once he said those words, my decision was made.”

Within a couple of years he was back at his old high school, the beginning of a long journey using the tools he had equipped himself with in Knoxville, his mother’s gift for broadening young minds clearly passed down to her youngest son.

No more travelling through the night on buses, no more mothballed motel rooms and no more football. After years of chaos and disorder, he was happy that was the case.

But then, well, something – everything – changed.

****************************

THE Marriott Hotel in Gaithersburg, Maryland and a conversation with an Irish lady called Denise Cunningham that would set Sherman Hall’s life on a completely different course.

“It was a split level bar, I’ll never forget it. I went there with friends but I spent the whole night standing on a stool talking to this beautiful woman.

“My wife actually came there to meet some other guy that night but he never showed up, thankfully. She was over nannying at the time, she just came to see America, and that’s how we became…”

The couple married in America in 1988, with daughter Shahara born the following year. After that, it was decision time – stay or go? Even though he was in his early 30s, with an established career, it was an easy call to make.

And when Hall first clasped hands with his new brother-in-law inside the Dublin airport arrivals hall, he had a feeling everything was going to be okay.

“When I saw Joey [Cunningham], I knew then I was home,” he says of meeting a man who, at that time, spent his Saturday afternoons terrorising Irish League defences in the red of Portadown.

“Now when I go back to the States I want to get back here as quick as I can. I don’t know what it is, I just felt at home here from very early… it’s as though it was meant to happen.

“And when you’re here, you have to decide what you’re going to do. I thought ‘what do I always do?’ – I’m involved with sports. I coach.”

Hall quickly hooked up with the local basketball club in Newry, who were playing in the Ulster League at the time. That soon transferred to coaching, and he eventually ended up helping out with the Irish team during the 1990s.

The basketball coaching also dovetailed with a growing involvement in Gaelic football, a path that led to him being deployed as a makeshift midfielder or full-forward with Forkhill.

His instructions were simple; catch all you can, pass to the closest man, and never, ever put your boot near that ball.

“Dessie McCoy, Peter McGeough and a couple of other boys got me involved, and when I did the youth club in Forkhill, these two kids - Darren King, who’s now a soccer player with Newry City, and Donal Murphy - used to come in early to teach me how to toe tap, fist pass... they were my first coaches in Gaelic football, those two boys.

“It was a culture shock. There were certain things you had to get used to…”

Such as?

“Well, such as one time I ran clean over the top of this guy and I went over to help him up, as you do - or as I would do.

“But all the boys were in my ear saying ‘buy him a pint after the game if you want, but don’t ever help his ass up…’”

Football has gone through several stages of evolution since those days.

On the inter-county scene in which Jemar is making his name, Dublin have been far and away the dominant force since the turn of the decade. This is the same Dublin who have utilised the skills of Jason Sherlock as a forwards coach during their march to four in-a-row.

A 1995 All-Ireland winner, Sherlock’s legendary status in the sky blue is long secured, but basketball was his first love. He played internationally up until U19 level and Jim Gavin felt that, allied to his obvious top level experience, Sherlock’s education on the hard court could offer the Dubs something unique.

How right he was.

“For it to really work, you have to get them at a young age,” says Hall, who has long believed that the skill sets and tactical nuances seen in basketball are easily transferable to the football field

“When Forkhill had their first ever basketball camp about 70 kids showed up – Paddy Burns and Stephen Sheridan play for Armagh, and my son, they were all in that camp. Stephen Sheridan is one of the best basketball players I’ve ever met.

“You have to know what you’re doing with the ball before your feet touch the ground – am I laying it off? Am I running? Am I going back to a safe place? Making those kind of decisions in a split second, that’s what basketball will do for you.

“So if you get that instilled, they will carry those skills and you’ll see that take off on the field.”

Passing on those skills and watching them develop, that’s why Sherman Hall started coaching in the first place. That was the buzz. Now 62 years old, the story remains the same.

This morning he will be at Newry leisure centre, tomorrow in the stands at the Athletic Grounds as Armagh welcome Cork, ready to talk afterwards - good or bad.

And the lessons learned from Mike Kanesky back in Montgomery High all those years ago remain at the very core of his own philosophy today.

“He wanted you to play with freedom, to play with no pressure. That’s the same thing I tell Jemar – play with this here,” says Hall, beating his chest, “and he plays with his heart on his sleeve and he enjoys himself when he’s playing.

“That’s why I still love coaching, no matter what I’m coaching. Watching a kid execute what you taught them... that never, ever gets old. Watching a kid love what they are doing is all you can really ask because that’s the most important thing - just to play. Just to play.”