ON Sunday afternoon, Stephen Cluxton could win a seventh All-Ireland title, and a sixth as captain. At 37, he remains the standard-bearer for an all-conquering team.

The mythological status that he’s earned across an 18-year career with Dublin is primarily down to what his wand of a left foot is able to do off a kicking tee.

The story is well-worn at this stage. Teams have become so wary of what he might do, they’ve stopped looking at what he’s actually doing.

For years, opposition teams have tried to analyse him. Tried to find some sort of secret, high-pitched Bat signal that only Dublin ears can hear. None have managed it, because there is none.

“My own opinion is that it’s not as set-piece at this stage,” says Meath manager Andy McEntee.

“The real beauty of Cluxton from a Dublin point of view is that he reads the game so well, he’s a good ball-player.

“They have set moves but within that, he’s still very much able to play what he sees in front of him.”

There has, however, been a noticeable difference this year in how often teams have forced him to kick long.

Largely due to sitting out the dead-rubber Tyrone game, and the fact that the All-Ireland final has yet to be played, he’s taken just 109 kickouts this summer so far compared to 159 last year.

But already teams have managed to contest 42 of his 109 (38.5 per cent), compared to just 46 of 159 last year (29 per cent).

_____________________________

Stephen Cluxton’s 2019 championship so far

Kickouts taken | 109

Kickouts won | 90 (82.6%)

Kickouts lost | 19 (17.4%)

Uncontested kickouts | 66 (60.5%)

Contested kickouts | 43 (39.5%)

Contested kickouts won | 24 (58.1%)

Contested kickouts lost | 19 (41.9%)

Saves | 6

High balls | 5/5 (100%)

Goals conceded | 2

Errors leading to goals | 0

_____________________________

Prior to the final, where Tyrone had joy with a zonal shape in the first 15 minutes, almost all of the contests last summer were man-to-man.

This year a lot of teams have managed to put some sort of zonal squeeze on that’s made him, at worst, think twice about going short.

And when teams have contested, the results don’t conform to the preconceptions. When Stephen Cluxton’s been forced to kick to midfield this summer, Dublin’s success rate off those restarts is just 58%.

Where Kerry can find joy against him is in knowing his habits. It may not be set-piece, but he still has a favourite out-ball like everyone else.

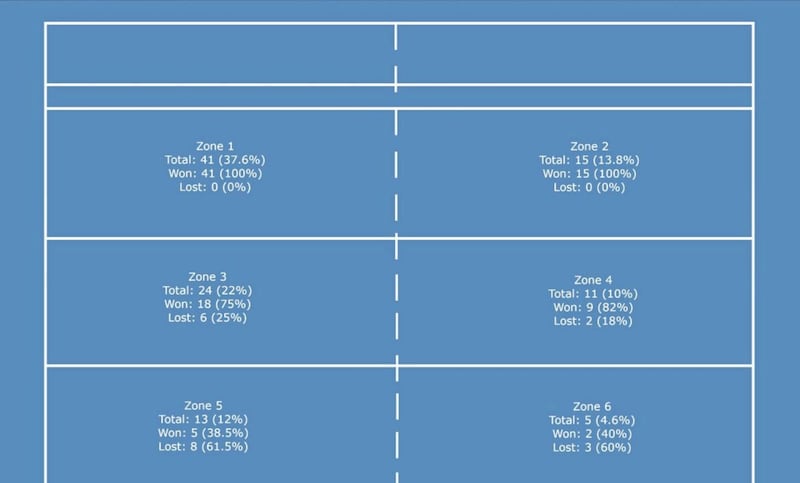

The first kick he’ll always look for is to the right corner-back area. He’s kicked more ball there than anywhere else this year. The area between the 13’ and 45’ to his right hand-side has been the target for 41 (37.6%) of his restarts.

The next biggest area is between the 45’ and 65’ on that side (24 kicks, 22%), and the area beyond the 65’ on the right wing is fourth with 12%.

In total, just under three-quarters of his kickouts (71.6%) have gone to the right wing.

“We’d have said if we were going to give him a corner to kick to, at least give him the left corner to kick to,” says McEntee.

“That’s the least of all evils. We didn’t over-commit to his kickouts.

“I think if anything, you’re trying to force him into areas he’d prefer not to go to. Giving him the opportunity of kicking to his left or his right, you’d want him kicking to his left, because he doesn’t get the same distance and he doesn’t have the same accuracy.

“If you’re going to give up a space, if you’re not in a position to go man-on-man and make sure he kicks it long, then give up his left corner. Kerry will be doing something similar, I imagine.”

They will have had three weeks to prepare where everyone else had a fortnight at most.

If you can force Cluxton to kick the ball long, you’ll give yourself a chance. If you can time it right and do it often, the better a chance you’ll give yourself.

Against Kildare, despite the beating they eventually took, Cian O’Neill’s side managed to contest nine of Cluxton’s 17 kickouts. Of those nine contests, Kildare won four.

In the semi-final against Mayo, James Horan’s side also contested the exact same number – nine of 17. But Mayo took the spoils, winning 5 of them to Dublin’s four.

The most kickouts he’s taken in a game this summer was against Cork, where the Rebels scored 1-17 and kicked seven wides.

They managed to get up and force Cluxton to kick 50-50 on ten of the 25 occasions he set the ball down. The sides won five each.

Meath were the only side that really went man-to-man against Dublin, rather than zonal. Yet they still got pressed up for 7 of the 15 kickouts that day, but won just two.

Teams have learnt from Dublin’s work in pressing the opposition kickout and become a lot more proficient at closing the Parnells man down.

He is human. But, despite the fact he’s only kicked beyond the centre-line on the pitch twice in the last two summers, there is the eternal threat of getting caught in behind by him.

“I think a lot of it is because teams are afraid to push up. With Paul Flynn’s demise, if you like, and Connolly not being there, that’s probably one of the reasons he doesn’t kick as long any more,” says the Meath boss.

“You’re missing two guys very capable of winning high, long ball if you decide to push up on them. Teams are probably a bit frightened to push up, because if that ball does go over the top, you’re left exposed.”

How you view that threat would perhaps be altered by the numbers as well.

Over the course of this championship, Dublin have scored 3-9 off the 24 long kickouts they’ve won. That’s a fairly handsome return.

But equally, the opposition have scored 2-5 off the 19 he’s lost. Cork and Mayo both got goals off it.

At what point does the reward outweight the risk?

Stephen Cluxton’s always been a problem for any opposition. Little bits of the code have been decrypted over years, but the best you’ll ever do off him is the 29% success rate (5/12) Mayo had in the semi-final.

And they were still obliterated.

Good luck Kerry.

***