Approaching the first anniversary of John Morrison's passing, his son and former Armagh goalkeeper Patrick Morrison sat down with Brendan Crossan to talk about the life and times of a true original...

Phone rings (John Morrison): ‘Hi Brendan, did you go and get your ferritin levels tested again?

‘Not yet, John, but I will.’

John: ‘Your levels are no-where near as high as mine, but just get them checked out. I’m sure they’re fine. Let me know how you get on…’

‘I will, John. Thanks. See you at The Athletic Grounds…’

Phone rings (John Morrison): ‘Hi Brendan, I just thought I’d give you a call to say I thoroughly enjoyed your article on Kevin Cassidy. It was measured and very well argued.’

'Thank you, John. I appreciate that. (45 minutes fly by)

Phone rings (John Morrison): ‘Hi Brendan, I just wanted to say thank you for what you wrote about Patrick in today’s Irish News.’

‘No need to thank me, John. Patrick deserved the plaudits. He never put a foot wrong all day. Who taught him that two-step kick-out technique? And that save at the end? Gordon Banks would’ve been proud of that one. Must have been some night in the Harps.’

John: ‘Your kind words were very much appreciated…'

‘How are things with you, John? Any more coaching books coming out?’

John: ‘Yes, actually I’ve one out at the minute. I’ll send you a copy.’ (45 minutes fly by)

Sunday October 15, 2017

ARMAGH Harps had waited 26 years to win a county title. You had to wade through a few dusty volumes to when the Harps last won a senior championship (1991).

They beat Maghery in the final that year too.

It was their third final appearance in four years (2014 and 2015) before they finally touched gold.

Under the floodlights of The Athletic Grounds, Patrick Morrison produced a performance that goalkeepers can only dream about.

If he played a better game in his career, then he must have achieved perfection. His two-step kick-outs were art itself.

That afternoon, Morrison was the consummate quarter-back. Unhurried and in absolute control.

Each placed ball floated into the arms of a Harps player before they'd launch another assault on Maghery’s goal.

The great thing about Morrison’s technique was that he was able to hit anything within a 180-degree radius.

A quick shuffle of his feet. Ping… Ping… Ping…

It was effortless.

Like an arrogant Frenchman, Morrison stood as upright as his lower vertebrae would allow him, he’d puff out his chest and survey the field like it was a blank canvas. His canvas.

“It’s a way of not looking hesitant and looking in control,” Patrick says. “Referees will always blow a ’keeper that looks hesitant.”

Trailing by four points, defending champions Maghery threw Ben Crealey in on the edge of the square in search of a goal.

In stoppage-time, Aidan Forker floated the perfect high ball in.

Crealey rose and changed the trajectory of the ball with a deft flick.

It looked destined to find the corner of the Harps net until Morrison made an outrageous one-handed save just as the ball came back up off the muddy turf.

Armagh Harps were champions.

A few days later, I interviewed Patrick Morrison for the first time about their brilliant victory.

As soon as he opened his mouth you knew he was John Morrison’s son.

Weaned on a diet of ‘Beefer’ philosophy, father-of-three Patrick had a clever phrase for every subject we spoke about.

Eagerly dismissing the weighty praise of his county final performance, he recited the sculptor-and-stone parable.

“There’s an old saying about the sculptor and the piece of stone. Everyone says to the sculptor that it was brilliant how he made that. And the sculptor says: ‘I didn’t do it at all – I just brushed away the hard edges.’

“The game is there – the coaching and coaching development brushes away those rough edges and makes the game what it is...

“The game is actually there – we’re just brushing off the rough edges. That’s the way I see it. And that’s listening to my Da for so long!”

*********

IT’S a manic Saturday afternoon in Camlough. There’s not a spare seat in the lively and welcoming Café Camocha that sits on the corner of the main street.

Just over two years from our first interview Patrick has agreed to a second.

How life has changed in the interim.

Next month, it will be John Morrison’s first anniversary.

I’m late. By the time I arrive Patrick has already had lunch and is sipping herbal tea and scribbling notes into an over-used notepad.

‘Don’t think it – ink it,’ John used to say.

An hour into the interview, Patrick gets to the nub of the grieving process and what life is like without his father.

He takes the notepad and pen and draws two squares side by side.

Both squares, he explains, are rooms. He draws a button in each square.

In the first square, he draws a massive circle that is touching the edges, and in the second square he draws a much smaller circle.

“At the start I just let the grief go, I just let it take me, get it out,” he says matter-of-factly.

“[Looking at his notepad] You’ve a room with a massive pain button and a big ball in the room and no matter where the ball is moving it’s always hitting the button.

“As time passes, the ball gets smaller, bounces around the room and doesn’t hit the button as much but when it does hit the button the pain is still the same, but it just hits the button less.”

John Morrison was a man who gorged on positivity.

Smiling, Patrick says: “I can never remember Da being negative. Everything was positive.

‘How are you, John?’

‘I’m wonderful,’ he'd say. ‘I can’t wait until tomorrow because I get better looking every day!’

“He knew positivity was infectious. If you were saying: ‘I’m not feeling too well,’ then you mightn’t feel too well yourself. But if you say: ‘I’m wonderful. I feel great,’ it grew on you.”

John, wife Maura and their four children – Emma, Catherine, Patrick and Sean – lived on Cathedral Road, beneath the magnificent shadow of St Patrick’s Cathedral in Armagh City.

“Da used to love sitting at the front door and if you passed him he would keep you for an hour if you’d let him. And they knew they were going to hear some cheesy jokes.

“Even the people out the road say they miss him sitting outside the front door.

“A guy rang him from a club one day and said: ‘John, I’m looking for an idea.’ And Da replied: ‘You’ve come to the wrong man.’

“And the fella says: ‘What?’

“You come to me if you’re looking hundreds. Not just one idea.”

“Ideas are like rabbits. You put two of them together and soon you’ll have hundreds.”

*********

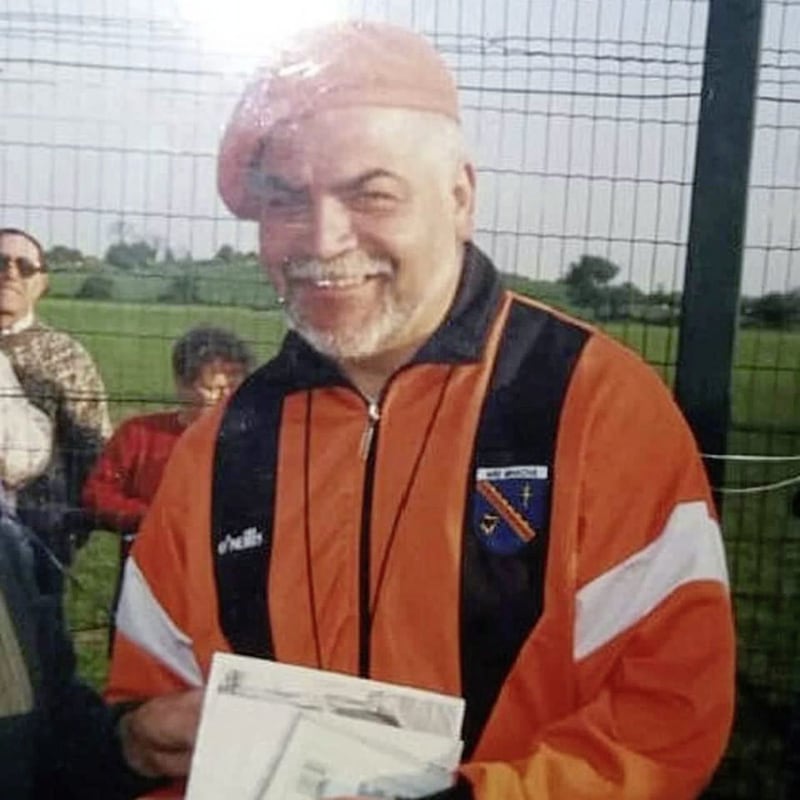

JOHN Morrison, affectionately known as ‘Beefer’, was always cut from a different cloth.

Charismatic. Engaging. Wise. Generous. Intuitive. A wordsmith. A philosopher. Prolific in every aspect of life. And always smiling.

‘Beefer’ was just different.

‘You laugh at me because I’m different – I laugh at you because you are all the same.’

By the time he reached the age of 40 he’d acquired no fewer than seven degrees – most of which were completed at Queen’s University.

He became a professor of Geography, a Doctor of Geology, gained a Masters in Town and Country Planning, a Masters in both Psychology and Sports Psychology, a degree in Teaching and one in Gaelic football before going to Limerick where he got an honours in Performance Coaching.

A schoolteacher for 35 years, John was a sports fanatic.

At Christian Brothers Primary School he was introduced to badminton, athletics, soccer, volleyball and table tennis.

In his younger days, he turned his hand to sprinting, discus, javelin and long jump.

“A few of his school friends and him started up a soccer team in Armagh City; they called the team Milford Everton. One of his friends, Eric Carson, lived in Milford and he was an Everton supporter, and Milford Everton was born (in 1964) and the club evolved into Armagh City, as it is known today.”

He held most posts in the Armagh Harps club too and his coaching expertise was always highly sought after.

“In the early 90s Da would’ve been with Blackwater. I remember him taking Sean and me to games – to give mammy a break.

“When we were old enough, we would’ve been kicking ball at one end of the field, as long as we were in eye shot of him. I was a bit older than Sean so he’d ask me to set out cones and stuff. We’d have the craic in the car.

“We always played the numbers game, guessing the end of car number plates on the way home.

“He was writing for the [Ulster] Gazette. Anywhere we’d go, the amount of people that knew him...”

Armagh was far from being insulated from the ‘Troubles’.

There was always a heavy British Army presence on the streets and the occasional flare up and exchange of insults, bricks and bottles.

John spotted an advert in the local newspaper where the youth club in the nearby St Patricks’ Hall was on the look-out for youth leaders.

“Once he seen it, my mummy and daddy had to help out,” says Patrick.

“Whenever they went there, they made a point of finding out what the kids were at. Were they in school? Did they drop out of school?

“And if they weren’t in school, they’d say: ‘That’s okay. Have you looked at other avenues you could try? School’s not for everybody. It’s not a crime. It’s a case of not giving up, just because you’ve tried one avenue.’ They would try and direct them, guide them.

“Whenever the youth club was over mummy and daddy would walk them home, and the army would shout at them.”

Laughing, Patrick recalls: “Da would get stopped by them and one time they accused him of running the youth wing of the IRA.

“I remember there were riots in Armagh and Da had just got out of the hospital after a heart operation and the rioters were across the road from our house.

“Da came out and stood on the wall. And you could hear some of them saying: ‘Jeez, there’s ‘Beefer’. Come on we’ll move down the road a bit.’

“That’s the kind of regard they had for him.”

*********

WHILE his father was spreading his unique coaching gospel to his ever-growing flock in every nook and cranny of Ulster and indeed further afield, sharing much of the journey with his friend Mickey Moran, his son wanted to get away from Gaelic football.

He wasn’t getting on the Harps team. He didn’t kick a ball for six years and ballooned to over 17 stone.

“My Da understood. I just told him: ‘I’m not enjoying it, Da. I’m not getting on and I don’t want to be there.’”

One day Patrick took a call from Harps manager Aidan Breen about coming back and doing goals.

“I was a midfielder until I was 24 but had done nets for school teams and Armagh minors. When I was there and there was a problem with the goalkeeper, I’d go in goal.

“So I just went back. The following year I started and that was 2014. That’s the year we got to the championship final…

“At that stage my legs had gone. I was 28. I drank and smoked the legs out of myself. But I decided to put my heart and soul into it...”

It was worth the effort. Patrick got his championship medal and spent four fruitful years with the Armagh seniors.

Now, just like his father, he’s imparting all the wisdom he’s accrued to the current Armagh minors alongside Ciaran McKeever and is studying physiotherapy.

“I get a lot out of coaching, the same thing Da used to get out of it – seeing people improve. His reward was seeing the wee lightbulb in the head going from: ‘I can’t do this’ to ‘I did that.’

“By the time a child has reached 10-years-of-age, they have heard a negative response at least 10,000 times: ‘Don’t do that’; ‘Stop climbing on that’; ‘You’ll fall’… That’s how they learn, but they’re told to stop. So they’re afraid to ask a question: ‘Should I ask that?’ ‘I’m afraid to look stupid.’ It’s about bringing that back out of them.”

*********

‘BEEFER’ never let ill-health rule him, until his very last days. He’d come out the other side of heart surgery, recovered from a stroke and overcome prostate cancer.

And he’d still be the first man in the press box of The Athletic Grounds, lightening the mood.

Up until his death, he was waiting to be put on the surgeon’s table for Atrial Stenosis – a serious heart valve disease where the valve widens to the point where it takes your breath away.

John never made it onto the operating table and died February 12 2019.

During the wake, their house on Cathedral Road never stopped.

Each room was packed with people who wanted to pay their respects and share their memories of ‘Beefer’.

“I was going to enjoy the wake, as strange as that may sound,” Patrick says. “The man who would’ve loved being there the most was who it was for.

“He would’ve loved hearing the old stories. For years he would have been on about getting a reunion organised for the old youth club that mummy and him helped run. He just never got around to it.

“A lot of the youth club ones were at the wake and were telling funny stories about their times at the youth club. I knew there was going to be a lot of people there but I didn’t expect the different people from different walks of life… the amount of people putting up their stories of Da, some of them I’d heard, some of them were new.

“There was one girl who said that a lot of the ones who went to the youth club probably wouldn’t have ended up in the careers that they ended up in because of mummy and daddy. That was very humbling to hear.”

On the day of his passing, the Ulster Gazette rang the house wondering where John’s column was and that they were holding back the press for it.

“He still had his last article in the drawer. He’d always write it by hand. He never typed in his life. It flew off the pen better. The Gazette used to say: ‘John, can you not type this out?’

“My sister had to tell the girl: ‘Daddy died this morning.’

“She probably got an awful shock. We found his notes in the drawer and we dropped them up to the office.”

The pen has since been passed to Patrick who continues the Morrison jottings in both the Ulster Gazette and Gaelic Life.

“His bedroom was full of scribbled notes and there were post-its everywhere, coaching books, story books… We’ve tidied it up a bit.

“He’s two pictures on the wall: one of the backyard, you’d swear it’s somewhere in Spain, the colours in it. He just loved that picture. And the other is of the strand in Newcastle and Slieve Donard.

“He loved going down to Newcastle and walking along the promenade.”

For Maura, Gemma, Catherine, Patrick and Sean, the ball and the pain button will always be there.

That’s the way life is now.

John Morrison was a one-off, someone who left a lasting impression everywhere he went.

He was just different from the rest of us.

Like a comet lighting up the black sky.

“He was a sculptor with everyone he met,” Patrick says, “even ringing you and telling you about your health complaint; that’s him brushing away the rough edges so that you spent less time wondering what was wrong and what you had to do, so that you had a straighter path. That’s just the way he was. It was never a problem. There was always an answer.”