HE PEERED through a forest of black boots and khaki uniforms to watch them box.

US Army soldiers went to war in a ring at Killymoon camp in Cookstown before they shipped out for the real thing against the Germans in Normandy.

A straight right hand, followed by a whiplash left hook and the GI went down.

The bell saved him and then his cornerman quickly ducked between the ropes to slap a wet sponge in the dazed fighter’s face and around the back of his burning neck.

A rub with a blood-strained towel and he got up off his stool and fought back. The soldiers watching roared and cheered. Soon it would be their turn.

Barney ‘BJ’ Eastwood, born in Cookstown, county Tyrone in 1932, loved it. The man-against-man drama, a test of skill and will, footwork and speed, bravery and bravado. He caught the boxing bug then and it has never left him.

“A lot of American soldiers came to different camps up our way,” BJ explains.

“There were some good fighters among them, some of them had been pros and they used to hold these tournaments between themselves.

“Then they would fight the British Army and the Navy had a team too. I got interested and then they used to match the schoolboys, I was always interested in it from there on.”

He was eight then and long after the soldiers had shipped out, their camp had been demolished and World War Two had been won, the inquisitive young man harnessed the passion of those days and built a fighting stable in Belfast.

Eastwood’s Gym was a beacon of hope in the middle of the Troubles, an oasis where men trained to fight but lived peaceful lives outside the ring. From that gym emerged world titlists Barry McGuigan, Dave ‘Boy’ McAuley, Cristanto Espana (the best Eastwood ever had), Eamon Loughran, Victor Cordoba and Paul Hodkinson and British and Commonwealth champions including Hugh Russell, Andy Holligan and Ray Close.

BJ could spot talent and get the best out of the men who had it. He travelled the world to learn the business and the world came to learn from him in that gym above a bookies’ shop in Castle Street.

A keen sportsman all his days, BJ took a few and gave a few slaps himself when his teacher cleared the desks at the end of the school day and let the lads pull on gloves and go at it.

“At three o’clock our teacher used to light a Goldflake cigarette, get the desks moved back and match different lads for boxing,” BJ recalls.

“Our class was always the best for Gaelic football and boxing. They used to bring the bigger boys in to box us so I was always interested in it – I don’t know which is the greatest part of my life, whether it would be boxing or Gaelic football.”

Football was a passion from his earliest days. He was blessed with a pace and a left foot but he had to borrow a ball to practice, practice, and practice.

“As a wee boy I remember a man called Joe Lawn,” he explains.

“Him and his wife used to look after the Cookstown jerseys; they were dark blue and dark red stripes and hand-knit.

“His house was near the pitch and I would go up and ask him for a lend of a ball for a couple of hours to kick about and I would go into the field and kick away.

“I loved doing that as often as I could get the ball. It was a big heavy, hand-sewn ball. There was a fella called McAnespie, he was a shoemaker, and he could make you a football. A pound it cost at that time, I remember that.

“So between that and watching the Americans and talking about boxing, I was interested in both sports.”

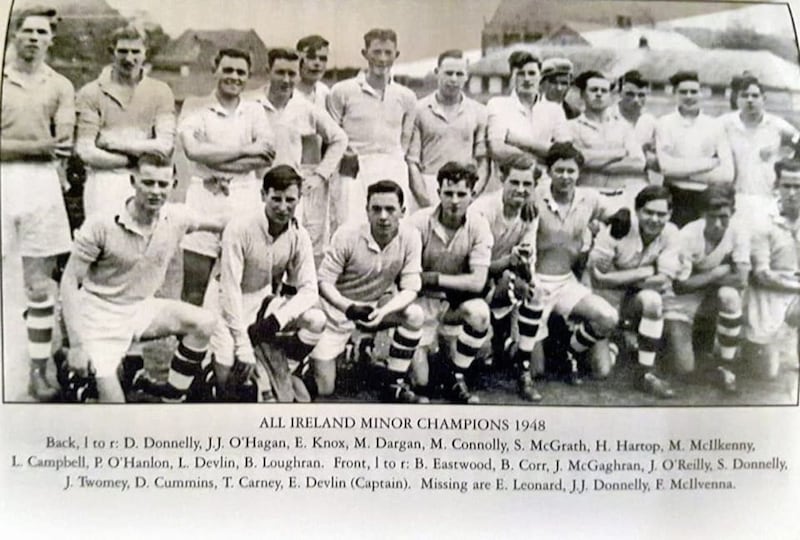

He played in street leagues in Cookstown – one of his adversaries was the grandfather of Owen ‘Mugsy’ Mulligan’s (“I also thought he was Tyrone’s Cantona,” says BJ) – and his practice paid off as word spread about the talented lad from Cookstown. Tyrone were sixty years away from a senior All-Ireland but even then there was ambition in the Red Hand county and underage structures were put in place to bring Tyrone’s best youngsters to the national stage. In 1947, Tyrone won their first minor All-Ireland and the following year BJ Eastwood, still only 16, was one of the names on the panel.

“I played for east Tyrone and then went to trials and got on the Tyrone minor panel,” says BJ, who by then had left his school days behind him – he was expelled from St Patrick’s, Armagh at the age of 14.

“There was quite a few good college players on the Tyrone team, a lot of them have passed away now, but in 1948 I got on the team anyway and we won our first couple of matches and then we won the Ulster final against Monaghan (BJ scored two goals and three points in a 5-7 to 2-3 rout on August 1).

“We played Galway in the semi-final. They were a tough team, they were all tough teams in those days. It was physical and the referees would let an awful lot of stuff go they wouldn’t dream of letting go today.

“To tell you the truth, I can’t remember what I scored in that game but I got a couple in the final against Dublin.”

He got more than a couple. BJ’s four points made the difference at Croke Park as the Red Hand youngsters beat the Dubs 0-11 to 1-5 to become the first county to win back-to-back minor titles.

The next day, The Irish News reported: “Tyrone excelled in all features to retain their title deservedly against a brilliant Dublin team”. BJ’s performance was described as “splendid”.

“Dublin was a good team and well organised,” he recalls.

“They were well-schooled and fitter than we were I would say but our team was probably more skilful.”

It’s a crying shame that the success of those minor sides didn’t translate into a Sam Maguire or two for Tyrone. The county’s first Ulster senior title didn’t arrive until 1956 and BJ wasn’t part of it. He didn’t go on to play at senior level and perhaps his experience is typical as a talented group of players quickly went their separate ways.

“I’m a Tyrone man, I was born a Tyrone man and I’ll always be a Tyrone man,” he says.

“I love Tyrone people and I always loved the football.

“But I gave the football up because of a change in circumstances. I got married (to Frances) when I was 19 (so was she) and bought a little pub and we went to live in Carrickfergus, a place I’d never been to in my life.”

Must-do is a great master but the self-confidence he had was remarkable. At the age of 19, a Catholic from Cookstown uprooting to Carrickfergus to run a pub? It would be unheard of today.

“When you're young you've no fear, you're full of beans,” he says.

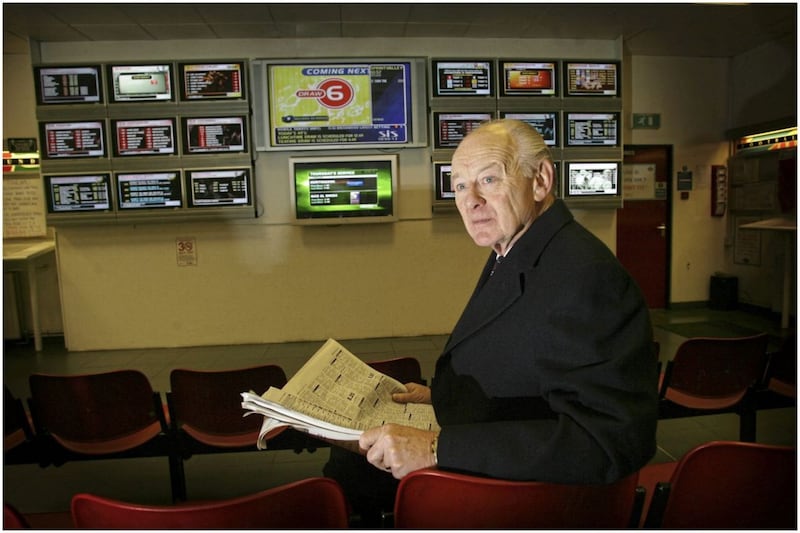

He had £2.50 in savings but, typically, he made a success of the pub and it inadvertently led him into the then illegal bookmaking business.

“It was a strange thing,” he says.

“A fella called Bob Gardner had the only betting shop in Carrickfergus; well it was more of a betting hut. The dockers would put bets on in it but he closed early. So when they came up that evening to collect their winnings, if the results were good, they couldn’t draw their money until the next day.

“A fella would come up to the pub and say: ‘That bookies’ is closed the day again’ so we started to take a few of the coupons as money and pay out on them. But then my biggest problem was getting the money off Bob Gardner.

“After a while I opened up my own betting shop in Carrickfergus.”

From those humble beginnings he built a chain of bookies shops that reached 54 at its peak and he sold up to Ladbrokes for £117.5 million in 2008.

While his business interests grew he continued to keep a close watch on the GAA.

“I always kept a great eye on how Tyrone were doing and the Gaelic in general,” he says.

“I started to go to the All-Ireland semi-finals and finals every year. I don’t know, I never counted, but the first All-Ireland final I was ever at was in 1943 (Roscommon v Cavan) and I’m sure I must have been at 60 since.”

Tickets came from a variety of sources and his friend, Galway great Sean Purcell agreed to sort him out with some for the 1956 decider.

“He said he would bring them up to me,” BJ recalls.

“I met him at a hotel and he arrived up in a big old jalopy of a car with six or seven people in it. He says: ‘This is so-and-so and this is so-and-so…’ They were all playing that day!

“It was half-two and he had half the team in the car. They weren’t leaving themselves much time.”

Purcell and his Galway team-mates beat Dublin that day and ‘The Master’ remains one of the greatest players BJ has seen and he’s seen and admired them all from Kerry’s five in-a-row stars to Dublin’s modern day genius Diarmuid Connolly.

“I saw some great players down the years and if they had been boxers they would have been world champions they were that good,” he says.

“Sean Purcell was a special player but when you get really down to it, Mikey Sheehy was exceptional, he did everything so easily and I watched him so often playing. I thought he was a dream.

“Maurice Fitzgerald was brilliant but, for me, Jack O’Shea was the best of the Kerry men.”

Rewind back to the pub in Carrickfergus and in between serving pints and taking bets, somehow he found the time to get back into boxing. Looking back, it’s no surprise that he found an outlet for his passion for sport, or maybe it found him.

He explains: “There was a wee amateur club and the fella who was running it was a pal of mine, he used to come into the pub.

“I helped him out in the gym a wee bit and I was keeping myself close to it. I always had a notion that maybe the right thing would turn up and I got involved in wee shows in the mid-1960s, first amateur shows and then wee professional shows and then I got involved with Mike Callaghan, who came to see me, and we ran a couple of shows in Larne and different places.

“We got going and got into the Ulster Hall and we went on from there. There was no television, no radio and the fighters got whatever money you lifted at the door. There has always been great support for boxing in Belfast and a lot of the guys who go to the fights are quite good judges of fighters.

“It has always been a fight city. If you go away back, prior to Rinty Monaghan and that, there were always fights and people interested and coaches here who kept it going in the amateurs. In the professional game it was never brought to the highest level and there were some good fighters who never made it.”

His first gym in the city was in a block of flats on the Falls Road. Like his early boxing days in Cookstown, there were soldiers around then too but this time they were an unwelcome distraction.

In the mid-60s there was a dispute with the Northern Ireland Area Board and life took him in other directions to greyhound racing, horse racing, the property market…

He returned to the noble art as a manager and promoter in the early 1980s when an exciting crop of fighters including a youngster from Monaghan called Barry McGuigan had come through.

“I had this old place lying on Castle Street and I thought: ‘This might do?’ So we turned it into a gym and it became Eastwood’s Gym,” he explains.

“Some great fighters came through that gym. Not alone my fighters but some great fighters that we flew in from Panama, Puerto Rico, the USA… We brought some great fighters to help out and spar with our fighters.”

Boxers, punchers, counter-punchers, brawlers, big guys, little guys, black, white, Catholic, Protestant… It didn’t matter.

They were all chasing the same dream and BJ made their dreams come true.