THERE was no fire and brimstone when The Master gave a team talk.

He rarely raised his voice but after Sean Smith had said his piece his players left the changingrooms with a clear gameplan in their heads and feeling, as former Bryansford captain Oliver Burns puts it: “Like you could beat anybody”.

Changingroom after changingroom, team after team; everywhere The Master went success was sure to go. Born in Maghery in county Armagh, Sean was an All-Ireland winner with the Orchard minors in 1949, but it was outside his native county’s borders that he forged his reputation as a creative, resourceful coach and a manager with the Midas touch.

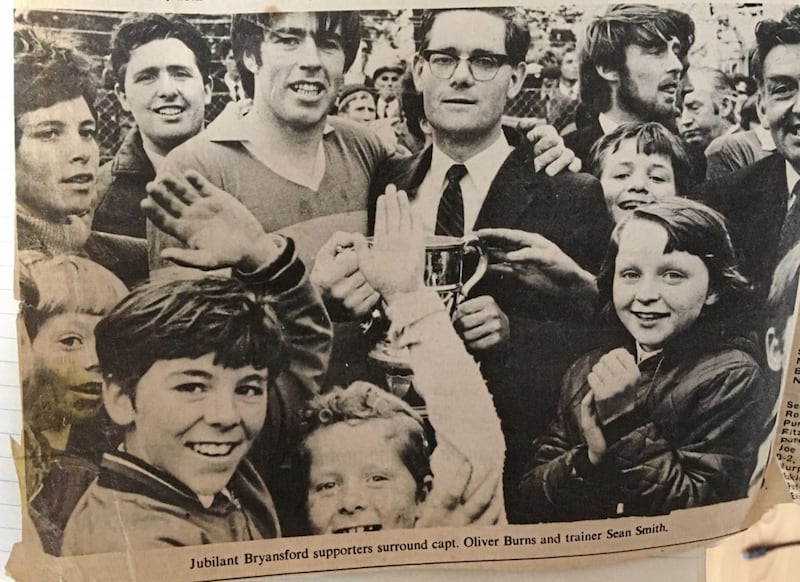

The schoolteacher, who passed away on February 5th at the age of 88, won Down and Ulster championships with Bryansford and then guided the club to the first-ever All-Ireland final.

He also celebrated county titles with Clonduff and Loughinisland, captured a cabinet full of trophies as Jordanstown manager and, in two spells between the great teams of the 1960s and the 1990s, took Down to Ulster finals in 1974, 1975 and 1986.

While squads throughout Ireland were trudging around heavy pitches on lap after lap, his players did calisthenics. When the others lined out in the traditional 6-2-6, Sean’s teams were playing a zonal defensive system.

A supreme tactician, innovator and lifelong student of the game, he was blessed with the ability to inspire the men around him and command their loyalty. No-one ever wanted to let him down.

Sean’s soubriquet ‘The Master’ came from his teaching days and work had taken him to Ardglass before he arrived in Bryansford parish in 1957 to take up a position at Burrenreagh Primary School. Construction of a new school was underway but Sean spent his first year in the dilapidated old building. One of his early duties was to deal with an unwanted visitor.

“On his first day he came, he caught a rat,” Oliver Burns, then a nine-year-old pupil, recalls.

“Somebody saw it and one of the youngsters had to go and get a trap. He set it and it was caught the next morning.”

The rodents kept their distance after that and life settled down as Sean became part of the community. He lined out for Bryansford when the club reformed in 1962 hoping to rekindle their glory days of the 1930s and ’40s when four Down titles were captured in-a-row.

But despite the addition of the former county minor star, Bryansford were languishing in the third of Down’s three leagues when his playing career ended. The struggles continued until his former pupil Burns approached to ask if he would manage the senior team.

“We always had great respect for him,” says Oliver, whose son Brian was an All-Ireland winner with Down in 1994.

“I always called him ‘Master’, I never called him Sean Smith, it was ‘Master’ right to the end.

“We used to go into the hall at Bryansford and put tables up and we’d be jumping over these tables and falling over them trying to get fit. We hadn’t a clue.

“So I went and asked him: ‘Will you manage us Master?’ And he did.”

Sean took over a collection of rough diamonds in 1966 and began to polish them up. It took a while for the players to accept his cutting-edge training techniques but winning a Down Junior title in his second season quickly convinced the doubters.

“At the start we thought he was a header,” Oliver admits.

“But everything he did worked, he was way, way ahead of his time - they are only coming up with things now that he was doing then.

“He maintained that we do the simple things: lifting the ball on your toe, passing, finding a man... “He used to say: ‘If you get the simple things right the other things will fall into place’ and he was 100 per cent right.

“He would go across to Leeds to see Don Revie (Leeds United manager) and come back with ideas and apply them to the GAA. He would have convinced you, you could beat anybody or do anything.

“There was an eight-foot fence around St Patrick’s Park and he would have had you thinking you could jump over it. He had that thing about him and he drove that confidence into you.”

One look at Oliver Burns and you’d know he was the full-back. A glance at Eugene Grant and you’d guess he was a corner-forward.

Brought up Belfast, Eugene brought a pinch of city swagger to the team and quickly earned the nickname ‘the kid’. He made his senior debut in 1968 and remembers being inspired by Sean’s meticulous attention to detail.

“As time goes on and you look back, the biggest memory was sitting in anticipation, you could hear the buzz of the crowd and smell the freshly-cut grass on a beautiful autumn day in Newcastle with St Patrick’s Park full and Sean Smith getting us ready,” says Eugene.

“The lower his voice, the more intensely you concentrated on what he was saying and when you were going out the door, you were just springing out of it.

“You knew from the moment you were in Sean’s presence that he had researched, not just Gaelic Football, but sport.

“He ate, slept and drank football. His love of sport, of the movement and the flow of the game... You had to learn to tackle, not foul and you learned how to buy a foul. I knew he had researched the great managers – Jock Stein, Revie… All the great managers of that time.

“He’d have you all round the world with his team-talks, so you never lost interest because you knew this man was always researching sport and applying it to what you were doing.

“I’ll never forget the night he came in and started talking about calisthenics. He came in and said: ‘We’re going to do this thing tonight, it’s for your muscle-development…’ We started doing these exercises, stuff that private trainers are charging a fortune for now.”

‘Calisthenics’ wasn’t the only unusual word Sean introduced to the Bryansford boys.

“You would have done an hour of backs against forwards and then he would stop the session and take time to explain something, sometimes he would walk through the moves,” Eugene explains.

“He used to use this word: ‘Impetus’. He used to say: ‘Impetus is what this game’s about lads’.

“He did that for months and then Oliver came up to me one night and whispered in my ear: ‘What in the name of God is impetus?’”

Maybe some of the players didn’t know what the word meant, but it turned out that impetus was exactly what Bryansford had.

From those humble beginnings, and with the more or less the same squad of players, Sean Smith built a team that won senior titles in 1969, 1970 and 1971, Ulster titles in 1969 and 1970 and reached the first-ever All-Ireland club final in 1971. (More about that in Monday’s Irish News)

Then in 1972, Sean was tempted away by a new teaching role in Antrim and he stepped down as Bryansford manager and tried his hand on the inter-county scene with Down.

In 1974, Sean’s Mourne county side beat his native Armagh in his first Championship match and then progressed to within a whisker of capturing an Ulster title but were held to a draw by Donegal in the final and lost the replay.

The following year, Down beat Antrim and Cavan but this time it was Derry that barred their way in the Anglo-Celt Cup decider.

The breakthrough evaded him and he returned to club football, guiding Bryansford to another Down title in 1977. He was appointed manager of Clonduff in 1980 and soon brought an end to ‘the Yellas’ 23-year wait for a championship title.

One of his early decisions was to bring a talented red-headed youngster called Ross Carr onto the senior squad.

“Clonduff weren’t going too well when he came in,” Carr recalls.

“He was a wonderful human being. He was infectious, so intense and in my opinion he was a coach way before his time.”

Carr had graduated to the Down senior team by the time Smith was tempted back to the inter-county scene in 1985. The Mournemen played four games (Donegal in the preliminary round, Monaghan, twice after a quarter-final draw and then Armagh) to get to the final but once again luck deserted Sean at Clones and Tyrone captured the Anglo-Celt on the way to their first ever All-Ireland final.

He had better fortune with Jordanstown. Either side of his second spell with Down, he had a 13-year association with the ‘Poly’ during which he guided various teams to Trench Cup, Hodges Figgis (Trench Cup winners versus Sigerson Cup winners) and All-Ireland Freshers titles.

“I couldn’t speak more highly of the man,” says Ulster University GAA lynchpin Tommy Joe Farrell.

“The first thing people will say about Sean is that he was a gentleman. It’s a word bandied about but he was a gentleman, an absolute gentleman.

“The second thing people say is that he was away ahead of his time and he was. They call it resistance running now but way back then he had the boys doing it with harnesses made out of bits and pieces, including his wife’s (Mary) tights.

“He had tackling drills called the ‘tin opener’ and he had running drills and forward drills – there was one he called ‘the spider’ – and he was a great reader of the game. He had a great way with him and the lads always responded. The training and the coaching he gave… At that time there was nobody else doing it.”

In all, Sean’s Poly teams reached nine finals and won the lot and he signed off on an historic note in 1993 after his Freshers side beat Queen’s at Corrigan Park.

After that win he hung up his bainisteoir’s bib and his whistle but never lost his boyish enthusiasm for the game.

Last October, Bryansford players from the halcyon days paid Sean a visit at his home in Ardglass. At 88, The Master had lost none of his passion and in a flash it was like they were back in St Patrick’s Park again as he lined them out and gave his former midfield star Cecil Ward (aged in his 70s) tips on how to tackle.

Sean had been in Croke Park for last year’s All-Ireland final and the replay in September (a visit he’d been making since 1960) and he remained his usual self, full of beans until a routine procedure flagged up a rash at Christmas.

“He had a bad hip, his walking wasn’t as good but he was still out in the garden and doing stuff like that,” Sean’s son Malachy explained.

“Then at Christmas he went for a cataract operation, he got both eyes done and the doctor said she had noticed a rash. So he went to the doctor the next Monday and the doctor sent him back to the hospital to get blood tests done. Whether there was an infection working on him or not, he got an infection and it turned into pneumonia.

“They tried four courses of anti-biotics and each time it seemed to be clearing but when the anti-biotics stopped it came back and the fourth course didn’t work at all.

“The doctor said that if you’re going to die at 88 it’s a good way to go because there’s no pain with it, it’s not like cancer, there’s no morphine or anything. His heartrate and his blood pressure were still fine but the lungs gave in in the end.

“It’s still very raw but it meant the family and everyone had a chance to say goodbye, it wasn’t like a heart-attack or something sudden so we had a bit of time to get our head around it.

“I would have preferred for him to go like he did rather than a long, slow illness where you see the life sapping out of him. That would have frustrated the life out of him.”

Like so many others Oliver, his former pupil and his captain at Bryansford, had called to see him before the end came.

“Me and him always had a great bond,” he said.

“It was hard to see him like that after all we’d been through over the years.”

On his last visit, Sean wasn’t able to speak at all and Oliver kept a silent vigil at his bedside for a while and then got up to leave.

He looked back as he reached the door and Sean raised his hand to say farewell.

Goodbye Master.