“Father, Son, Holy Spirit, Amen.

Lord, we thank you for the gift of our health to be able to play football.

We pray that we go out and do our best; we respect each other; we respect the referee and others.

We pray that we play to the best we can.

We ask this prayer through Christ, Our Lord. Amen.

RIGHT BOYS, COME ON NOW TO F***!”

THE prayer Frank Diamond said in the changing room was always loosely the same.

He devoted 22 years of his life as a seminarian and then Missionary Priest. He also played football in a lot of places.

The youngest squad member for Lavey’s All-Ireland senior club success in 1991, he was back in Croke Park 16 years later with Eoghan Rua, Coleraine for an All-Ireland intermediate final.

In between there were a clatter of Derry reserve championship medals with Bellaghy, a Down junior title with Glenn when he was the only serving clergyman playing Gaelic football, spells with Young Irelands in Philadelphia and Sons of Eireann in Northampton.

Diamond was also captain of all his school teams the whole way up through St Mary’s Magherafelt, and led Maynooth’s Sigerson Cup team.

The family farm in the townland of Ballymacpeake was the second-last house on the Lavey side of the parish divide with Bellaghy.

None of John and Chrissie Diamond’s six offspring, of which Frank was the eldest, were that mad into the 2,000 pigs and 40-odd cattle they kept.

The children worked themselves hard but it was a sense of duty rather than a labour of love.

Peter, the youngest, had been starved of oxygen in birth and has lived with additional needs.

The family’s isolation on the farm hadn’t helped him and with their father’s back struggling with the work, they moved into the town of Bellaghy in 1992.

Frank tells the story of how, when he was 16, Peter came sprinting up out of his bedroom, bouncing for joy, saying over and over: ‘I can do it!’

“We didn’t know what he was on about. I said ‘what is it Peter, what can you do?’

“‘I can tie my own shoelaces!’

“For him, at 16, that was like winning £1m.

“Peter is without doubt the greatest gift that God has blessed our family with.”

The youngest sibling had started to withdraw from society when the decision was made to move into Bellaghy town.

That meant a transfer of sporting allegiances for the family. Frank had played all the way up on good Lavey teams but would humbly admit that his brother Cathal was the coveted footballer in the house, going on to win a handful of senior medals with Bellaghy and briefly feature for Derry.

For Peter, it was a defining move. He’s been involved in coaching Bellaghy underage teams - including their Ulster minor winning squad from 2018/19 - and has enjoyed such thriving purpose, normality and acceptance in life.

The GAA has always been such an important part of their lives.

When Gerard O’Kane was recently asked to recount a memory from his days playing with Derry, he chose the 2002 All-Ireland minor final.

Fr Frank, as he was at the time and up until 2012 when he made his final decision to leave the priesthood, had been asked by Derry manager Chris Brown to say mass for the players in Dublin on the morning of the game.

As O’Kane climbed the Hogan Stand steps to lift the Tom Markham Cup, there three seats back is Frank Diamond, the collar poking out through his replica jersey.

He’s invited down to the pitch with the players and doesn’t hesitate. In the celebration photos taken in front of Hill 16, there he is on his hunkers with the players and the Tom Markham Cup.

“It was one of the best days of my life. Unreal! The power of the collar!” laughs the 48-year-old.

He came to end up in Coleraine after pausing his vocational life and taking up a teaching post in North Coast Integrated College.

Friends and connections he’d made there, mostly through the Dromantine summer camps, brought him into the Eoghan Rua fold and he ended up corner-back on the team that went to an All-Ireland intermediate final in the 2006/07 season.

The first Monday night in April, a few weeks after the decider, Coleraine Borough Council – a traditionally unionist body – held a civic reception for the team.

When they arrived, they were met by a gang of loyalists, waving Union Jacks and wearing Rangers jerseys, blocking the front entrance to the council buildings.

"I think for 15 protesters to turn up and stand in front of the main door of the council building and to have to bring the young team in through a side exit was certainly very, very disappointing,” said the town’s UUP mayor at the time, William King.

Part of Diamond wishes it had been the week before the game, so they could have used it as motivation in their narrow defeat by Kerry’s Ardfert.

But aside from the “crushing disappointment”, his abiding memory was how Eoghan Rua’s opponents treated them that night in Croke Park.

“Ardfert lined up and gave us a guard of honour as we came off the pitch. I’ll never forget it.

“They’d done their research on Coleraine, they knew the neck of the woods we were from. Their manager came in and gave a brilliant speech about how proud they were of us and what we were dealing with.”

It was only when his calves started popping at the age of 41 that he had to give up on the idea of adding the over-35s of Kildare’s Sarsfields to his list of clubs.

His daughters, Carina (6) and Laoise (5), are down at the club every Saturday morning at the GAA for All sessions.

Laoise was born with Down Syndrome.

At a year old, she underwent seven-hour open-heart surgery to repair two leaking valves.

On Tuesday past, she celebrated her fifth birthday.

“She’s the apple of everybody’s eye, not just mine. She teaches me so much.

“Resilience, every day. It’s the wee milestones like learning to walk. It takes that wee bit longer but she keeps getting up. They fall, they get up, they keep ploughing on.

“Learning the sign language, speech therapy, a bit of physio and she’s getting there in her own wee way.

“I’d always have heard people saying about wee ones with Down Syndrome giving the best hugs, and they do, they absolutely do.”

* * * * * * * *

THE Land Rover Discovery was taxi, ambulance, delivery suite and hearse for the people of the small Tanzanian village of Kilulu.

Being away from home had never been easy. When he decided to join the priesthood, the first year with the SMA (Society of Missions to Africa) was a spiritual retreat in Cork.

He was only 18.

When Lavey beat Dungiven to reach the county final, he begged to be allowed go up. The answer was no.

Then they found themselves in the Ulster final, and he asked a second time. No.

When they overcame Thomas Davis in the All-Ireland semi-final, Diamond was determined to take the place that Brendan Convery had kept for him on the squad.

His superiors relented and allowed him to go to Dublin for the decider against Salthill.

“I never prayed as much in my life as sitting on that bench. The final whistle went and it was pure ecstasy. I fell on my two knees and thanking God.

“There’s a photo of us all up behind Johnny McGurk on the podium, and the next thing the boys said ‘Frankie, sing Back Home In Derry!’ So I started singing it on the Hogan Stand podium! It was fantastic.”

His team-mates refused to let him go back to Cork, and stuck him on the bus up north. He had to ring down to his superiors from the Carrickdale Hotel, insisting he’d be on the first train the following morning.

Cork for a year. Maynooth for a while. Zambia for a year. Then from 1998 until 2002, Nigeria. Three straight summers back out to Zambia with Friends of Africa. Then 2008 to 2011 in Tanzania.

In 1999, he ended up being the Republic of Ireland U20 football team’s chaplain for the World Cup in Nigeria.

That was Brian Kerr’s team containing Robbie Keane and Damien Duff, the latter a devout Catholic, the former always handy with Joxer Goes To Stuttgart when Diamond produced the guitar in the evening.

His abode would seem like squalor but it was relative luxury.

He had a camping stove and the chickens, goats and ducks the missionaries bred themselves meant there was meat for one meal a day.

They were able to filter and boil water to wash with.

The natives had no electricity, running water, flushing toilets, often food itself.

“You really appreciate the simple things in life and take nothing for granted.”

It was rewarding work, but very often lonely and laced with hardships.

Living on the edge of the Serengeti National Park, he lived sights that would change any person’s perspective on life.

Burials were common. Imagine committing a tiny baby who died of malaria into the ground in a cardboard box, out in the middle of a field.

Rushing two teenagers to hospital an hour away after the kerosene lamp they were using at night-time exploded.

“The two lads were burnt all over. I went down and it was lashing the rain, they were pink and roaring in pain with these burns all over their bodies.

“We got them to the local hospital and there were no beds, we had to lie them down on a mat on the concrete floor. There was no doctor.

“The nurse came, and they were trying to find a vein to put in a drip, and they had to go through their feet because they couldn’t get a vein. They were screaming in agony.”

They set off the following day on a five-hour trip to the main hospital in Mwanza, but one of the boys, Paul, died a day later.

Frank had to go and bring his body back to the village.

“We buried him in the bush, beside the family’s mud hut. It’s heartbreaking. Things like that affect you.”

There was a birth too. A lady landed at his door in very late labour, struggling.

“Ten minutes from arrival at the hospital, didn’t she give birth in the back of my Land Rover! Some craic. Now I’m not great with that stuff back then, the roaring and all the rest.

“Thank God everything was grand, everyone was well. A week later, she walked up to the mission house with the newborn baby, to show me, and she was carrying a live chicken by the legs. She handed me the chicken to say thank you for helping her.”

That was all the woman owned, and she gave it to him.

That was the mark of the people he found, not just in Kilulu, but in Mufulira or Kabompo in Zambia, or Kontagora in Nigeria.

Malaria caused so much death around him. Nine times he contracted it himself. On four of those occasions, he required the ‘last resort treatment’, a quinine drip, to keep him alive.

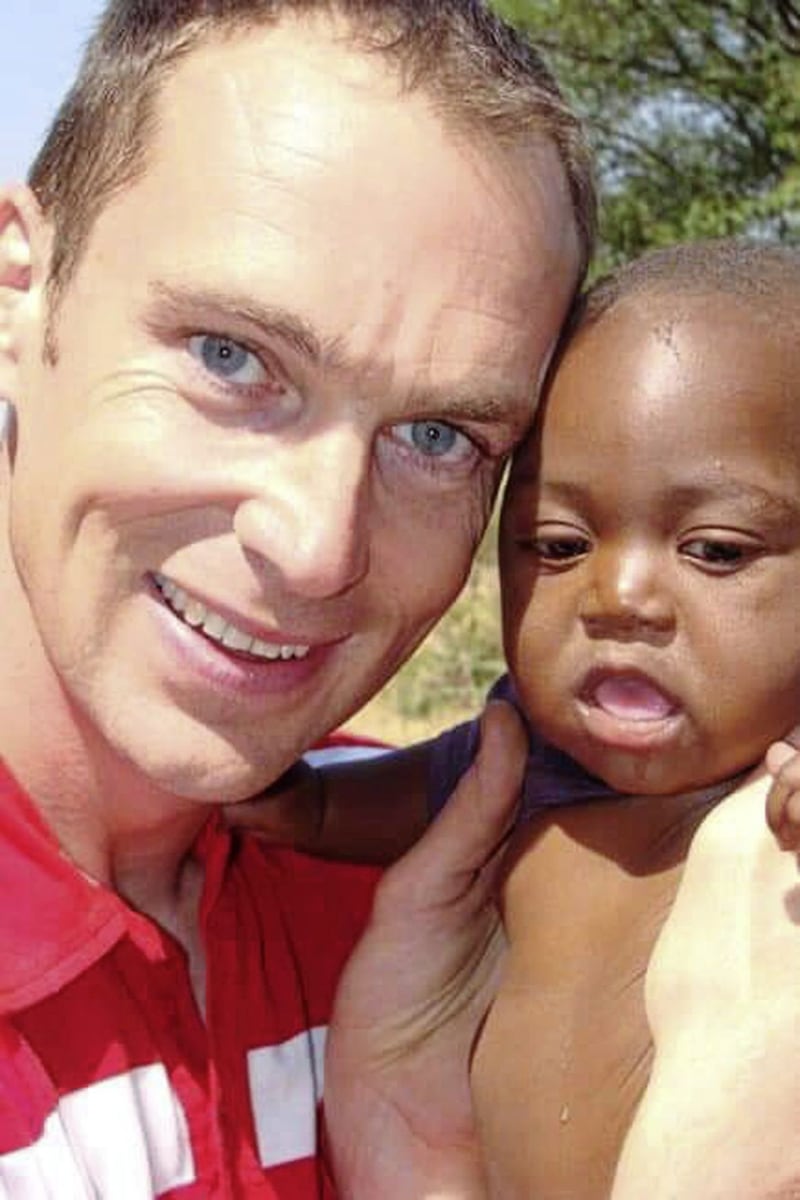

There’s no feeling, though, like the joy of helping kids, be it reading or learning the chorus of Back Home In Derry, dancing around the campfire or playing soccer as the natives wonder at ‘Tembo’, meaning ‘White Elephant’.

“I often think back to those nights and the power of human connection.

“I’ve all these wee munchkins singing ‘Oh-oh-oh-oh, I wish I was back home in Derry’. They haven’t a clue where Derry is, but are they happy? Absolutely.

“The simplicity of life, that whole community and being connected with singing, music, telling stories – we could learn so much from that.

“We need to bring that model back here to Ireland to help with our mental health. Young ones now are in their rooms with their phones, going through Instagram, Tik Tok, they think they’re connected but it’s so false.

“They’re not connected at all. We need that human connection back again. The community thing, I learnt from the Africans as well as the GAA. Building communities is what it’s all about.”

* * * * * * * *

“Is the work you’re doing now more important than the work you were doing as a priest?”

THE question makes him pause.

Frank Diamond left the priesthood in 2012 after years of wrestling with the Catholic Church’s ideals, but never the idea of his own faith.

That the Church in England has now welcomed in scores of former married Anglican priests, many of whom are fathers, while others are still expected to maintain a vow of celibacy? Doesn’t make sense, to all of the 100,000-plus who have left the priesthood and got married in recent years.

“It was the hardest decision I ever had to make but I just knew I wasn’t happy within myself. I was fairly lonely and looking 10, 15 years down the road, the average age of the SMA priests was about 110 and I was going to be the last man standing.

“I wouldn’t have my two little girls if I hadn’t made it, and they’re the greatest gift in my life. No matter what happens, they’ll always be there.”

He’d always wanted other things in his life, but above all he wanted to help.

Last August he took up a post with the non-profit, Downpatrick-based outfit ALPS, whose primary concern is with mental health and suicide prevention.

Since he joined, more than 30 clubs have taken part in the group’s QPR [Question, Persuasion, Referral] training, which teaches people how to deal with a crisis situation if someone they know is feeling suicidal.

“The role I’m in now, it’s a humanitarian thing rather than a religious thing, and trying to save lives…

“From a spiritual end as a priest, you’re trying to help people with their journey of faith. This role now is trying to save people’s life, in many ways.

“It would probably be greater in that respect.”

Frank Diamond is one of those people that fills a room the minute he walks in. A seemingly permanent ball of radiant energy.

Yet his knowledge of the mental health issues with which he deals is partly informed by his own struggles.

He’s not immune. He’ll feel it coming on when he doesn’t want to get up in the morning, or doesn’t have the drive to go and exercise.

Even Frank needs to talk.

“There are times when I thought I could do everything, I’m a giver, but there’s only so much you can give and then you burn out. My tank was on empty.

“When that happens, there’s no self-care and that’s when negative stuff can come in. I reach out at that point and have a chat with somebody.

“Sometimes it’s a counsellor, and definitely with friends. I’ve learnt that, to be honest and frank about it, but I wasn’t always like that.

“To my own detriment at times, I’m very honest. I wear my heart on my sleeve and you can be judged on that very quickly. But I am who I am, that’s what makes up Frank Diamond and I’m not gonna change that.

“If there’s anything I can do to help anybody, I’ll do it. We all need somebody to lean on.”