“YOU talk about losing an All-Ireland final. It doesn’t...” Andrew McCann’s voice lowers as he pauses and looks up and out the window at the far side of the room.

Outside, weeks of unrelenting sunshine seem like a distant memory as the skies above the Meath townland of Monknewtown give way to sheets of rain. The McCanns have lived in this house for three years now and, after a bit of shifting about, this is where they’ll stay.

His wife Emma’s parents live just next door. Slane’s pitch is less than a mile down the road, a patch of green McCann has got to know better than most thanks to regular stints smoothing the surface on a ride-on.

The couple’s three boys - Eoin (17), Joe (10) and Cormac (8) – all play underage with the club, and all support the Royal County in a big way. That their dad is part of an exclusive group of Armagh All-Ireland winners has no bearing on this.

Sitting around the kitchen table, a fair bit of the morning is spent chatting about different things. The challenges as well as some of the unexpected joys of lockdown life, how schools will manage come September, how little he misses those rush hours journeys to and back from work on Dublin’s northside.

Mostly, though, we talk about him. It is a subject he is not, and has never really been, entirely comfortable with. Think of the Armagh 2002 team, and McCann has managed to steer clear of the public eye more than most. This is not by accident.

His understated, almost bashful demeanour always felt somewhat at odds with that Orchard crew’s fearsome reputation. In their early Noughties pomp a life or death intensity dripped from every fibre of their being. He bought into all aspects of that.

The good days were celebrated while the bad – and, let’s face facts, it doesn’t get much worse than losing your All-Ireland title to the noisy neighbours - can still conjure feelings of pain and frustration all these years on.

But those are only fleeting moments that tend to pass as quickly as they arrive because life, he knows, is about so much more than the game.

On July 29, 2006 the McCann family was plunged into grief when baby daughter Caoimhe died in a car crash near Kilkeel, Co Down. She was only nine months old.

“After something like that,” he says quietly, eyes still fixed on the falling rain, “everything pales into insignificance.”

*****************

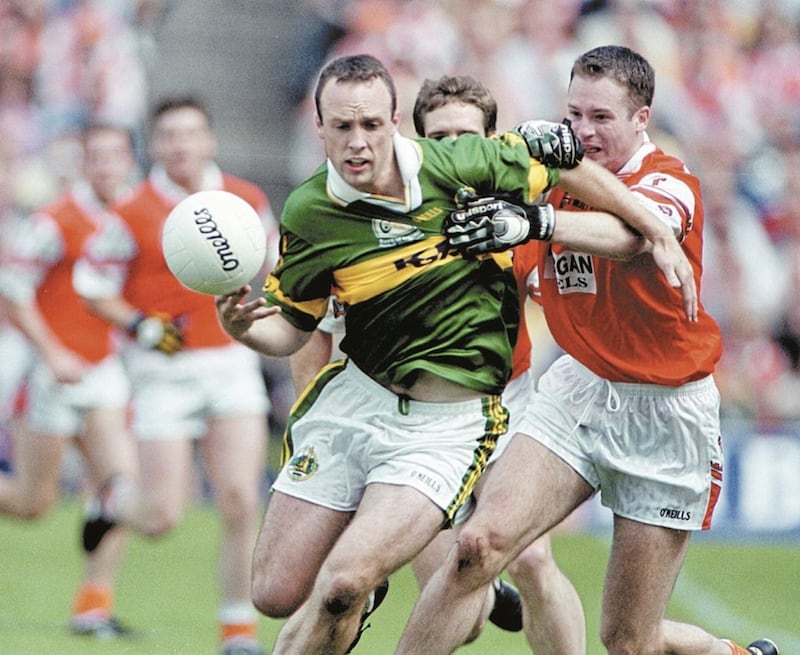

TRAILING by three staring down the throat of added time, dreams of edging closer to Sam were slipping from Armagh’s grasp once more. Twelve months earlier it was another green and gold giant who had spoiled the party when Sean Boylan’s grizzled Meath side quelled the northern uprising.

The Orchard were back at the All-Ireland semi-final stage in 2000, a year older, a year wiser, but facing the same sorry outcome. With 14 minutes remaining a piece of Maurice Fitzgerald magic put Kerry in the box seat heading down the straight.

Armagh weren’t done yet though. In the 69th minute the ball was worked up the field where Diarmaid Marsden found himself confronted by two Kerry defenders on the edge of the square. Out of the corner of his eye he spotted Andrew McCann ghosting forward off his left shoulder. The Portadown man didn’t break stride as he received Marsden’s fist pass on the run before drilling low beneath Declan O’Keefe to level it up.

The Orchard faithful had a new darling that day. A last-gasp Fitzgerald point may have saved Kerry’s bacon and secured a replay after Kieran McGeeney steered the Ulster champions ahead, but it was McCann’s intervention that had breathed new life into what looked a lost cause.

Heading for home, the Armagh team bus stopped at the lights at the top of Jones’s Road, waiting to turn right onto Clonliffe Road. Benny Tierney was the first to spot him.

Soon, the whole bus was looking out the window, watching as McCann - hair still wet, gear bag over his shoulder - weaved through the crowd just as he had done the Kerry defence an hour earlier. Armagh fans were moving the same direction too but nobody stopped him, the hero of the hour slipping seamlessly into the shadows again.

“I probably didn’t justify a high profile,” he laughs.

“I was just walking to the car like everybody else. I was living in Dublin, so to get the bus back to Armagh then get myself back down… just the logistics of it, it didn’t make any sense.

“I dunno… I’d say it’s just my personality. I enjoyed playing football, that was it. Anything after that wasn’t really my scene. I just enjoyed playing the games.”

Twenty-six then, he was at the peak of his powers. And yet days like this would have been unimaginable a decade earlier.

Growing up, McCann, his uncles and his father Seamus would pack up every Sunday and follow Armagh across the country. Around the mid to late 1980s and early ’90, they hadn’t much to celebrate. But that never seemed to matter - he just wanted to play.

To fulfil those ambitions, however, he would have to do it the hard way.

“When I was very young I lived in Down so started with Tullylish. I went to primary school in Laurencetown, James McCartan was at the school at the time, three or four years older than me, but he stood out even then. When we moved to Portadown, I went to Tir na nOg and played through from U12 to senior.

“There’s a great club there, Sean Gallagher was the man who coached me right the way up. He was the guy who would’ve pushed me on, especially when it came to getting involved with the Armagh minors in 1992.

“He gave me the confidence to go into that environment, drove me up and got me to join in. You’re going up to the first couple of training sessions with that Armagh team… the vast majority of them were guys who played for MacRory Cup teams - St Colman’s, the Abbey, St Pat’s, Armagh. People who go into those schools, it’s maybe engrained into them that way.

“I went to Lismore Comprehensive, my dad taught there. There wouldn’t have been a big emphasis on Gaelic then. Those first training sessions up at the playing fields in Armagh, running around, up hills… I wouldn’t have been used to that. I still wouldn’t have been 10 years later!

“I was starting at a bit of a disadvantage from everybody else.”

A team backboned by the likes of Justin McNulty, Paul McGrane, Diarmaid Marsden and Barry O’Hagan won Ulster and went on to the All-Ireland final. Although they lost by a point to Meath, green shoots of recovery were emerging in a county starved of success for too long.

McCann came off the bench in the semi-final and final, and was happy enough with that having only joined midway through the minor league. Yet while making the transition to the senior stage is never a given, doing so away from the leading lights of Armagh football makes that task all the more tough.

Indeed, by the time the mid-’90s rolled around, Portadown was attracting attention on an international scale for all the wrong reasons. Every July the stand-off between Orangemen and residents of the Garvaghey Road would push tensions in the town to the very brink.

Drumcree Church, the scene of so many ugly exchanges throughout that tumultuous time, is just a mile from Ballyoran Park where Tir na nOg play. The McCann family home isn’t too much further away.

He can remember the sound of Ian Paisley’s booming voice echoing across the countryside on a summer’s evening, while another day he watched as an armour-plated bulldozer trundled past his front door towards Drumcree. Minutes later it would threaten to storm the police line that waited.

McCann shakes his head as he thinks back.

“It wasn’t long before that GAA members were put down as legitimate targets [by loyalist paramilitaries]. I remember playing for Queen’s and there’d have been police Landrovers around the side of the pitch.

“Where the club is, it’s in a Catholic area of town in a housing estate, it’s kind of cocooned to an extent… it wasn’t something that was really in your head. There would have been security concerns, keeping the gates closed, making sure nobody got in who shouldn’t have got in.

“It was a strange time but lots of clubs, especially around Belfast, had similar issues. In Portadown you wouldn’t have a great pick of numbers but a lot of work went in to keep it going.”

Faced with adversity, Tir na nOg gritted their teeth and got on with it. In 1996 they enjoyed a rare foray into Armagh’s top flight and it was then that he made the breakthrough.

McCann had struggled for minutes when drafted into the county panel before but the new Orchard management team of Brian McAlinden and Brian Canavan travelled to Ballyoran Park, they liked what they saw.

“We were playing Crossmaglen that day. Obviously the guts of that Cross team would go on to sweep the boards in the years to come, so we must have done okay…”

Naturally athletic, a dogged man-marker but blessed with the uncanny ability to ghost into space unnoticed, he soon became a mainstay under the two Brians. With a new Orchard crop just about ready to bloom, the future looked orange.

“When I went in first the main guys on the team would’ve been the likes of Jarlath, the Grimley twins, Neil Smyth, ‘Houly’… all guys you would have watched as a kid and looked up to.

The team that was eventually successful, most of those guys were around my age so we came along together pretty much.

“There were no superstars, it was putting the head down and trying to make things better.”

And they did, in some style. A 17-year wait for Ulster glory was ended with a demolition of old foes Down in the 1999 final before they repeated the trick the following July.

Now, all eyes switched towards the big one. With Crossmaglen the dominant force at provincial and national level, Armagh had to capitalise on the inter-county stage while the going was so good.

Still, though, they found themselves frustrated.

After losing out to Kerry in the 2000 semi-final replay, before a qualifier exit to eventual All-Ireland champions Galway in 2001, Joe Kernan – the man behind Cross’s remarkable run of success – was brought in to bridge the gap.

It was now or never.

“You’d always fear that. It’s happened for a lot of teams – look at Mayo. We were at a crossroads, but I don’t think our group ever lost belief.

“There was this whole thing in the media at the time that Armagh can’t win in Croke Park. You could very easily let that get into your head. A combination of the strength of character within the group and the good footballers we had helped us get over that.

“Lesser teams could have been swamped by it or never got over those defeats. We were knocking on that door but, you know, in the life of a football team, three or four years is a long enough time…”

By the following September, Armagh had reached the promised land, reaping revenge on the Kingdom in the decider to spark scenes of delirium inside Croke Park.

A familiar McCann run was the catalyst for the Orchard’s vital second half goal as he glided down the left before off-loading to Oisin McConville.

“Don’t mention steps,” he smiles.

McConville burst forward, popped it off to McGrane who palmed it back down into the path of the Crossmaglen man as he bounded towards the small square. In that moment, there were no safer pair of hands.

“Ah look, they’re great memories – the Citywest that night, the bus journey up home, the City Hotel in Armagh with all the lads and the families. Obviously it’s something you’ve done and you’re proud of it, but the main thing for me was probably the enjoyment my dad and my brothers and sisters got.

“Apart from that, you move on and do something else.”

That pragmatic approach would serve him well on the other side of the coin too, and never moreso than in the aftermath of the 2003 All-Ireland final defeat to Tyrone.

“The disappointment was just on a scale you can’t describe really, but my first son was born a couple of weeks after so your priorities soon change. There’s something else to take your mind off it.

“Being down in Dublin probably made it easier to deal with too – you were far away from Armagh but, more importantly, you were further away from Tyrone. I wouldn’t say it took me weeks or months to get over, it’s still something that pops into your head from time to time, but there’s nothing you can do about it.

“I’ve never watched it. I don’t think I would.”

********************

FOR eight years Andrew McCann had done the hard slog until, eventually, he could take no more. A job with Hewlett Packard had brought him to Dublin in 1997, the drive up and down the M1 to training becoming a staple for the majority of his inter-county career.

Some nights he’d travel with Des Mackin, or Enda McNulty, or Kieran McGeeney, sometimes with all three. But eventually the time away from home, from Emma and their young family, began to grind. At 31, his priorities had evolved.

An All-Ireland medal, four Ulsters, he could be happy with his lot. He still loved football and, playing at wing-forward, would go on to help Meath club Seneschalstown land county championships in 2007 – their first in 13 years - and 2009.

There was no pomp or ceremony when he walked away. No grand announcement. In typical fashion, he slipped out the side door while no-one was looking.

The slower pace suited down to the ground but when tragedy struck that terrible July day, their world was flipped on its head. Fourteen years on Caoimhe remains a part of their lives and, over time, they have learned to cope with their loss.

But the pain is always there, and always will be. Tough days on the field? All-Ireland heartache? They fade into the ether.

Life is so much bigger than the game

“It’s difficult to talk about… it was just something we had to try and deal with.

“Eoin had a few scrapes [from the accident], Emma had broken ribs. I remember at the time when they were brought into the Royal in Belfast Kevin McElvanna, one of the lads on the Armagh panel, he was treating Eoin. It was good to see a familiar face at that stage.

“Emma, she dealt with everything brilliantly, much better than I did. Everyone deals with things differently – I probably deal with things by not talking about them, where Emma would want to talk about things all the time, but we’ve managed to live our lives and cope with it.

“We go into her garden, as we call it, it’s in the village in Slane there, and leave flowers. The two youngest lads were born after that, they didn’t know her but they talk about her. Eoin was only three so he doesn’t remember… it’s something you hope you never have to deal with.

“No matter what you’ve done or what’s happening, it changes everything. Something like that, whether it’s football or work or whatever, it puts it all into perspective.”