I REMEMBER with great fondness the hazy summer of 1982 and the World Cup finals in Spain.

I remember BBC and ITV’s theme music. And Brazil. It was all about Brazil.

Those golden jerseys, sky blue shorts and bright white socks.

Now that was a proper football kit.

I couldn’t wait to watch Zico.

As kids, our only reference point to this glorious footballer with flowing locks was a couple of action pictures that appeared in Shoot magazine - the children's bible growing up.

The rest was left to our imagination.

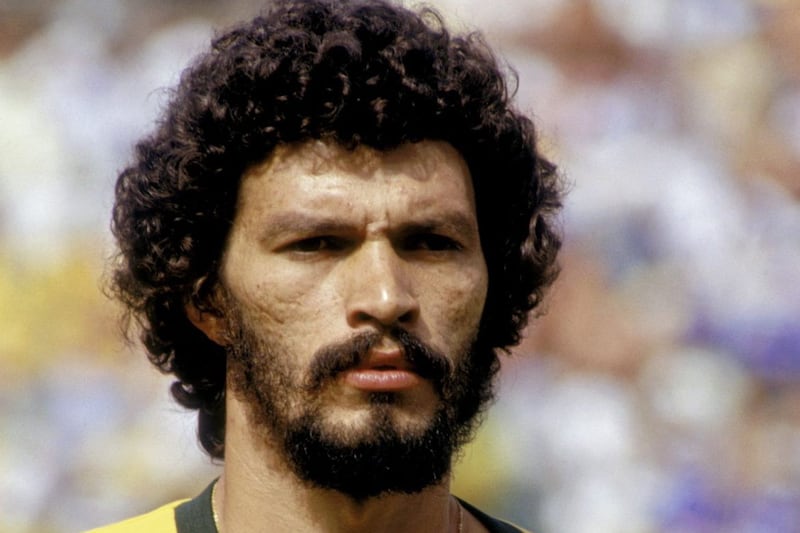

The general of this special Brazilian national team was not Zico, my father insisted, but Socrates.

A qualified doctor, Socrates was the bearded metronome of the team.

Standing a slender 6ft 4in, the Corinthians player was a picture of elegance and a paragon of calm on a football pitch.

On a balmy evening in Seville with Brazil trailing 1-0 to an impressive USSR side, and time running out, Socrates produced a moment of magic.

Thirty yards from goal, he feigned to shoot twice before thundering the ball beyond the hapless Rinat Dasayev in the Soviet goal.

With a few minutes remaining Brazil grabbed the winner with an even better goal from flamboyant winger Eder.

Brazil were off to a flyer.

No matter how much time passes, the archives of that famous Brazil side of '82 still glow as brightly as ever.

Tele Santana's team, led by the swaggering Socrates, was football in art form.

Back then we knew little about these players that lit up our television screens for a month.

There was no Wikipedia, no YouTube footage.

Once the World Cup was over, we never saw them until four years later.

Sometimes we never saw them again.

Snippets of information about these exotic players were scant. What we knew was that Socrates was a chain-smoker who loved beer.

He cut the figure of a happy-go-lucky, guitar-playing, lefty who played football for the love of the game.

Brazil-based journalist Andrew Downie's recently published biography of the bearded genius, entitled ‘Doctor Socrates: Footballer, Philosopher, Legend’, confirms that all these things were in fact true.

Downie’s meticulously researched 384 pages, which includes extracts from the player’s unpublished memoirs, delve into every nook and cranny of Socrates’s life and is a brilliant read.

It charts his early years in Ribeirao Preto where he was undecided between practising medicine and pursuing a career in football.

After much soul-searching he picked football, because it was his dream to play in a World Cup.

He became an emerging star with Corinthians, one of Brazil’s biggest clubs.

A serial womaniser, Socrates married four times. He partied hard during his playing days.

Before the 1982 World Cup finals, he quit smoking so that he could be in peak physical condition for the tournament.

He also embarked on a strict fitness regime.

“He gave up everything,” recalls team-mate Zico, “and was one of the fittest guys we had at the tournament. At that World Cup he was focused on being in top form and that was what happened.”

In the late 1970s and early 80s, Brazil was ruled by military dictatorship.

While he had no interest in party politics, Socrates displayed a strong social conscience from his early days in professional football.

During his time at Botafogo, around 1977, Socrates was mindful of the money the players were earning while other people that helped run the club were less well off.

Downie writes: “Socrates thought the masseur, the laundry woman and the stadium janitor played almost as important role as the right back, the reserve goalkeeper… and proposed that they take a percentage of the win bonuses.”

Later, not long after joining Corinthians, Socrates persuaded his new team-mates to do the same.

Although it was some way off, these gestures of generosity were the genesis of what became known as 'Corinthians Democracy'.

The free-spirited footballer felt that the football club model was all wrong and that it merely reflected the inequalities of Brazilian society, so he sought to dismantle the club’s hierarchy, replacing it with a fairer system where everyone – be it a club director or tea lady – had one vote each and this determined how the club was run.

The players would vote on mundane things such as when they should eat to what new players the club should sign.

At its heart were accountability and responsibility.

It was a revolutionary idea that gathered incredible momentum, largely because Corinthians were having plenty of success on the field.

In many ways, 'Corinthians Democracy' would not have enjoyed the success it did without the team performing well.

Footballers, for a short time, became the engine for change in Brazil.

'Corinthians Democracy' became a major thorn in the side of Brazil’s military dictatorship as more of its citizens pushed for democratic elections.

Biro-Biro, a Corinthians team-mate of Socrates, recalled: “Our responsibility grew. We created a democracy that had an effect on the whole country. And every game was a final.”

Socrates, an established Brazilian international by 1980, became the face of the the movement.

Intellectuals, musicians and artists flocked to 'Corinthians Democracy' – but when Socrates decided to move to Italian club Fiorentina, the movement lost one of its main drivers.

Although 'Corinthians Democracy' couldn't force democratic elections, it played a key role in loosening the military’s grip on power.

On the field, Socrates never fulfilled his dream of winning a World Cup.

Italy famously defeated Brazil 3-2 in an unforgettable game at the ’82 finals.

Socrates never watched a re-run of the game until many years later while sitting in a bar with a friend in Japan.

“I was chatting away and the game came on and I started to glance at it and then watched the whole thing,” Socrates recalled.

“I was transfixed. I thought it was f****** brilliant, an amazing game, fantastic, I think the best game I had ever seen in my life and I had never watched it before. What a game. I don’t like to look back… but there it was and I watched it.”

In 1990, the two sides replayed the game in Pescara – as a farewell match for Brazilian defender Junior – and Brazil won 9-1.

In Mexico ’86, Socrates graced our television screens again, but he wasn’t half the player.

His physical powers had been eroded by living the high life.

In later life he struggled to contain his drinking.

He died on December 4 2011 of food poisoning, aged 57.

For anyone who remembers the summer of ’82 and watched Socrates weave his magic, Andrew Downie’s book on the footballer, philosopher and legend is a must-read.