KEN Doherty was sat watching the Tommy Tiernan Show a few months back when a familiar figure strode out from behind the screen, a coat-hanger smile taking over the comedian’s face as announcer Fred Cooke revealed the identity of his first mystery guest.

Because before Monaghan actress Charlene McKenna spoke about her career, before Brush Shiels gave Tommy a lesson in incantation, there was Jimmy.

Through the 1980s Dubliner Doherty had grown up watching Jimmy White on the tiny TV in the corner of the front room. Alongside Dennis Taylor and Alex ‘Hurricane’ Higgins, he was among the superstars with whom the young man dreamt of one day sharing a stage.

“Even for Tommy,” says Doherty, “Tommy would’ve played around the snooker halls in Navan when he was younger. That’s probably why he was so delighted to see him come out.

“For anybody of that generation, Jimmy’s a bit of a hero.”

As the interview unfolded, White relived some of the escapades from an at times crazy, rock and roll existence – the drink, the drugs, the excess. Sober for six years, he can laugh ruefully about it all now.

“These days I get up at half 11 in the morning instead of going to bed at half 11 in the morning…”

But the one habit Jimmy White can never kick is snooker. This is where the conversation turns serious.

Despite turning 60 in a month, despite not having qualified for the World Championship since 2008, despite the last of his six final defeats at the Crucible coming a few weeks after Kurt Cobain died, he still believes he can land the big one.

Seconds of silence pass as Tiernan’s glare meets his.

“People are like ‘you're crazy’ but I know I'm not.

“And I know I've got an unbelievable chance. I'm not putting myself under pressure when I say that, because it's my belief.”

At the English Institute of Sport in Sheffield next week, Doherty - like White - will begin his latest quest to qualify for the World Championship.

It is eight years since he last parted the curtain at the Crucible theatre, 25 since a childhood dream was realised in a swirling blur of photographer’s flash and thunderous applause.

Never mind winning, just to get back out there and feel the buzz one last time, he’d give anything for that.

“I’m a bit more realistic than Jimmy. Am I surprised at Jimmy saying that? No, not really, because I know the way he thinks.

“I admire Jimmy for his belief, his love of the game still. I admire his ambition. I mean, when I look at somebody like Jimmy and his name isn’t on the World Championship trophy, that’s a tragedy.

“It makes you appreciate all the more that yours is…”

**********************

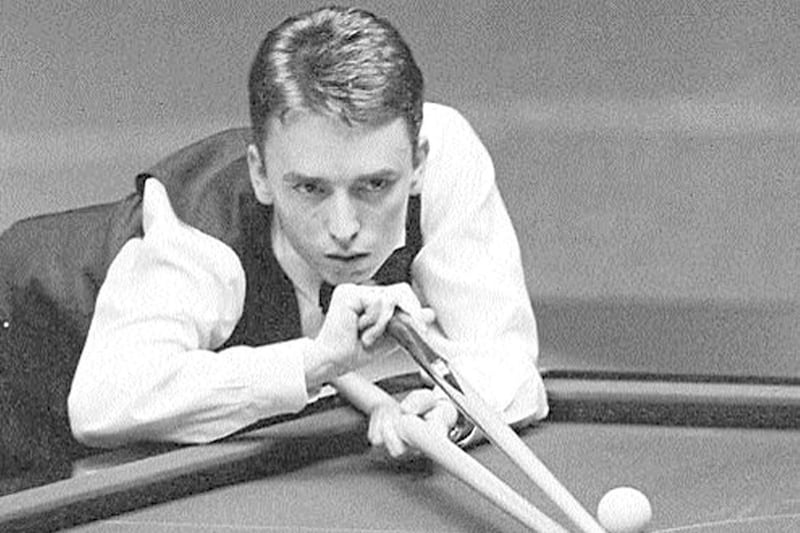

STEPHEN Hendry’s aura had most opponents licked without a ball being struck. By the time their paths first crossed as teenagers, Ken Doherty knew all about this formidable talent coming through the ranks.

Everyone did.

“I first met Stephen when I was 14, he was 15, playing international snooker in Prestatyn. He had this great air about him, chest out like he owned the place.

“Even then he was aloof, and he stayed like that to an extent, but I know him a lot more now. We’re friends, colleagues on the TV. I still remind him about ’97 when I can… I was actually in a Chinese restaurant in London there a while back and it was called Old Town 97, so I made sure I sent him a picture.

“But he’s different now too. Back then, he wanted to separate himself from everyone else, to keep distance - wouldn’t talk to you on match day, wouldn’t look at you. He didn’t want you to be comfortable in his environment.”

Yet when they walked out together for the first session of that famous World Championship final, Doherty stood tall and smiled, breathing in every second.

Those of a certain vintage will remember what a force Hendry was at this time - an ice cool customer gunning for a seventh World crown in eight years, his domination of the sport so unrelenting punters were willing anybody to knock him from his lofty perch.

But Doherty’s own education in the sport brought with it a hard edge that came in handy on occasions just like this.

“My father used to watch Pot Black and the World Championship, and then I got a little snooker table at the end of my bunk bed one Christmas when I was eight - from then on I was hooked.

“I used to frequent Jason’s, the snooker club in Ranelagh, and I’d empty the ashtrays, sweep the floors, do anything to get a free game of snooker or Space Invaders. That was the only place I wanted to be.

“My school teacher used to say ‘Doherty, forget about snooker – snooker clubs are only frequented by smokers, drinkers, gamblers and unemployed layabouts,’ and I’d say to him ‘sorry sir, but I don’t smoke…’”

That familiar machine gun laugh lets rip. Untold hours spent in dimly-lit halls, those were the days alright.

And it was there, in Jason’s, where Doherty fell in love for the first time.

“I was only 11 when I found this cue on the pool rack,” he says, lifting the case up onto his hotel bed.

“I asked the manager could I keep it if nobody came back to claim it and he said, in his broad Dublin accent, ‘if you giveiz a bleedin’ fiver you can have it’.

“So I went around to the mother, begged and borrowed five pound off her, promised I’d pay her back. I got five pound notes from the Post Office, put three in one pocket, two in the other, and went with the poor mouth approach – ‘my mother can’t afford five, she can only afford two’.

“He looked at the cue, looked at the two pound, and that was it. I’m still using it to this day.”

That hustler’s spirit served him well at the table too, Doherty’s nous belying his tender years and helping ease financial burden at the most trying of times.

When dad Tony died in 1983, he left behind wife Rose, sons Seamus, Anthony, 13-year-old Ken and the baby of the house, daughter Rosemarie. With his mother working four jobs to try and make ends meet, Ken lightened the load any chance he got.

“I used to get 20 quid a week off the owner of Jason’s, and I’d head straight into town on the bus with the cue, trying to spin it up to 40 quid, 60…

“Sometimes I’d come back to the house, my mother already would be in bed and I’d come in off the last bus home about 11 o’clock, go straight to her room and rustle the money up beside her ear. She’d wake up with a big smile on her face, because there was days I’d come back with a hundred quid.

“I could make more on a Saturday than my mother would make in a week.”

When he had £500 saved up, Doherty boarded a boat for England in search of fame and fortune. Although her boy’s brilliance was beyond doubt, Rose remained unconvinced.

“She was sceptical,” he smiles, “even when I had been a professional for a few years, if I had a bad loss or something, she’d say ‘would you not give up that bloody game and get a real job’.”

Over time, though, that leap of faith, the belief that he had what it took to succeed, would reap rich rewards. But toppling Hendry was the high bar.

If allowed to get in among the balls and play, the Scotsman was unstoppable. Doherty learned this the hard way in the 1994 UK Championship final, though it is for reasons beyond the baize that match stays in his mind.

Trailing an on-fire Hendry 7-5 at the interval, Eamon Dunphy made his way into Doherty’s dressing room at the interval, the colourful and often controversial pundit determined to deliver some words of inspiration in his friend’s hour of need.

“I’m sat sulking in my chair when Eamon bursts in with a cup of tea in his hand and he’s shaking, spilling the tea everywhere.

“You have him - he’s f**king gone. Listen to me, you have him by the bollocks.”

“Eamon, calm down, he’s in the next dressing room, the walls are paper thin, he’ll hear you...”

“I f**king hope he hears me!”

“He’s just made six centuries in seven frames, what do you mean he’s gone?”

“He can’t play any better! I’m telling you…”

Doherty breaks off the following frame, Hendry pots a long red - the start of another centuy. He then rattles off the next two to take a 10-5 victory.

“And Dunphy’s the first one up to shake Hendry’s hand afterwards,” laughs Doherty, “‘ahhh Stephen, you’re the greatest player ever’. All over him like a rash.

“It was classic Eamon.”

Yet that one-sided affair bucked the trend of an increasingly competitive and, for Hendry, frustrating rivalry.

“Some players I know I can bully into submission; Ken will stand up to any demonstration of that and isn’t fazed by my reputation,” he wrote in his 2018 autobiography, Me and the Table.

“In fact, he even seems to relish playing me, and that makes me irritable in a way I’ve not noticed before.”

Hendry had also gone into the 1997 World Championship with his laser-like focus shaken by the arrival of a disturbing letter weeks before he headed to Sheffield.

“As I read, my stomach lurches over. In a scribbled hand, the writer sends a warning about the forthcoming World Championship. He (or she – it’s anonymous) claims to know where I live, and where Mandy walks with Blaine in his pram.

“If I win the world title this year, the writer promises they will throw acid into my child’s face. The final sentence reads: ‘Black ball, black death’.”

“No way,” says Doherty when the extract is relayed, “I didn’t know that... oh Jesus, that’s crazy. I wasn’t aware of that at all. That’s shocking really. Very scary stuff.

“It’s just sport at the end of the day. Nobody deserves that.”

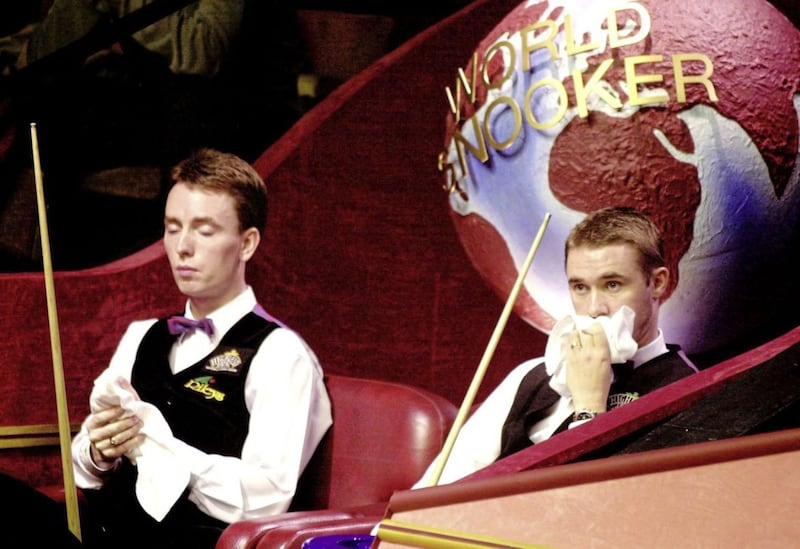

Despite considering withdrawal before the competition, Hendry eventually decided to defend his trophy. But when he reached the final hurdle, Doherty was waiting – and ready for whatever psychological warfare came his way.

“I’d never really done much in the World Championship before then but when I get through to the final, I was so excited about playing Stephen that I couldn’t sleep. He was the benchmark.

“You couldn’t let him intimidate you. You had to show him you weren’t afraid, and I wasn’t. I knew I couldn’t outscore him – he was the best long potter, the best break builder. I knew I couldn’t beat him at that kind of game. He didn’t particularly enjoy the safety side so my best chance of winning was with good matchplay snooker.

“He wanted the balls open, he wanted to score, where I didn’t mind scrapping.”

‘Crafty Ken’, the hustler, the scourge of snooker halls across Dublin years before, back on familiar ground. And as the final found its flow on the first day, Doherty sensed something different in Hendry.

“I doubled a re-spotted black to go 7-4 up, and we both went to the toilet afterwards. When he came in he said ‘I knew you’d get that’, shaking his head as if to say ‘lucky bastard’. I just smiled and said ‘you should never leave a mug a double’.

“But it was strange… unlike him. When he said that, you think maybe his head isn’t in it. Like, if I’d walked in and seen him standing at the urinal, I’d have probably gone into the cubicle, so it was quite unusual for him to do that.

“He was obviously thinking negative things about himself and positive things about me.”

In the hotel that night, Doherty visualised lifting the trophy, “giving it a big kiss like Alex and Dennis had done”. With a commanding 15-9 lead heading into the last session, dream was about to become reality.

Typically Hendry came out firing, picking off the first three frames to heap pressure onto the Dubliner’s shoulders. But Doherty stayed calm, nicking the last before the mid-session interval – and from there he didn’t look back, holding his nerve all the way to a stunning 18-12 triumph.

“I looked over to the press seats and saw Tony Drago with that big smile on his face, and that started me smiling. I looked up to my friends in the crowd. I thought of Alex Higgins and my dad, who watched Alex’s 1982 victory with me…

“I just wished he could have been there to see me do it.”

**********************

BACK in Ranelagh, journalists, TV cameras and half the street had piled into the Doherty home for the final few frames. Ken’s siblings were there to welcome them all in – but mum Rose was nowhere to be seen.

“She’d gone out on her bike. She didn’t come over to Sheffield because of the nerves; she couldn’t even take watching it on the TV.

“Usually mam would’ve went to Clarendon Street but she ended up out in Donnybrook church, lighting candles and saying prayers. That’s where her and dad were married.

“On the way back home she got a puncture, she ended up having to walk, pushing the bike the whole way. There was no mobile phones or anything like that so she hadn’t a clue what was going on with me.

“But then eventually somebody stopped her and said ‘congratulations, your son has just become world champion’.”

When Doherty arrived back in Dublin, Rose was waiting at the bottom of the airplane steps. Amongst all the dignatories, amid all the fanfare, he only had eyes for her.

“I gave the trophy straight to mam… she was so proud. She put it on the top of her TV, every day she’d give it a kiss and get it shined up so that it sparkled. People would come in and take photographs with it – the door was always open.

“That trophy was paraded at Old Trafford, Croke Park, Lansdowne Road, but it belonged in my mother’s front room.”

Since Rose passed away on Mother’s Day in 2017, just three weeks after being diagnosed with pancreatic cancer, this time of year always throws up conflicting emotions.

“It’s hard because she was a huge figure for us… she was very strong – she had to be. It was very difficult for her after my father died, but she was a great influence, a very loving mother. A big inspiration for me.

“But here I am getting ready to go again… still haven’t got a real job.”

On Friday, Doherty will face the winner of the round one clash between Rory McLeod and Ng On-yee. It could be the start of a beautiful journey, or it could be the end of the road.

At 52 the clock is ticking, with each passing year the gap widens. But the opportunity to get back out there - the introductions, the crowd – it always brings him back for more.

“Ah look, I don’t know how much longer I’m going to play. If I don’t see any improvement… I still love playing, but not getting results you would like is tough.

“I can’t perform like I used to and I have to accept that. It’s like anything - you can’t do what you could do 25 years ago. You just have to come to terms with it.

“But I’d love to have one last hurrah before I hang up my two pound cue for good.”